This essay is part of the book Public Finance for the Future We Want, you can find the entire collection of essays here.

Across the political spectrum, conventional wisdom holds that technology and finance remain the greatest obstacles to moving society beyond fossil fuel dependency. Yet, neither is the real reason why progress on climate action has stalled for decades. Solar applications alone have the technical potential to provide 100 times more electricity than the United States currently consumes, as concluded by the Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory in 2012.2 In the world’s richest nation, which created trillions of dollars to save banks between 2008 and 2014, financing is not the problem either.3 The United States can wield its sovereign monetary power to finance and encourage investment in non-extractive energy projects as part of a Green New Deal to address the climate crisis and economic inequality. Why, then, do oil and gas companies still seek new reserves, governments still licence dangerous infrastructure, banks still finance carbon-intensive projects and investors still embrace fossil fuel companies?

The short answer is that the US government has no interest in going after the fossil fuel industry, the source of the climate mess. In fact, the very opposite is true, with governments bending over backwards to help this industry. At best, politicians and officials find ways to deflect attention from root causes, focusing on only one side of the climate equation: demand. Demand-side initiatives aim to decrease our use of fossil fuel products by, for example, giving tax breaks to companies that make more efficient light bulbs or by supporting renewables. By free market logic, decreased demand for fossil fuel equals a decrease in supply, so focusing on demand-side initiatives is the ‘logical’ way to advance climate action while not directly confronting the fossil fuel industry.

But is it really? First and foremost, ours is not a free market. Real solutions to the unfolding climate crisis must include the supply side of the climate equation. As time runs out for mitigating the worst that is yet to come, pace will have to equal scale. Without undermining all-important complementa- ry state and local initiatives, we need to reclaim political will at the highest level: the federal government.

Untangling government through the federal reserve (and a public buyout)

Fossil fuel companies’ domineering political influence is the real problem. We need to dismantle this powerful roadblock to an environmentally viable energy system and have a plan for managing this industry’s decline. Strong regulations will not do it. If reserves stay largely under private control, the regulatory approach would be too complicated and time-consuming. Unchecked, fossil fuel companies’ opposition machinery could hold back progress indefinitely.

Since 85 per cent of the known fossil fuel reserves need to remain unburned, we must figure out how best to use the other 15 per cent to support a clean, equitable energy transition.3 With reserves in many different hands, and with diverse private interests at play, this already tough question becomes harder to answer.

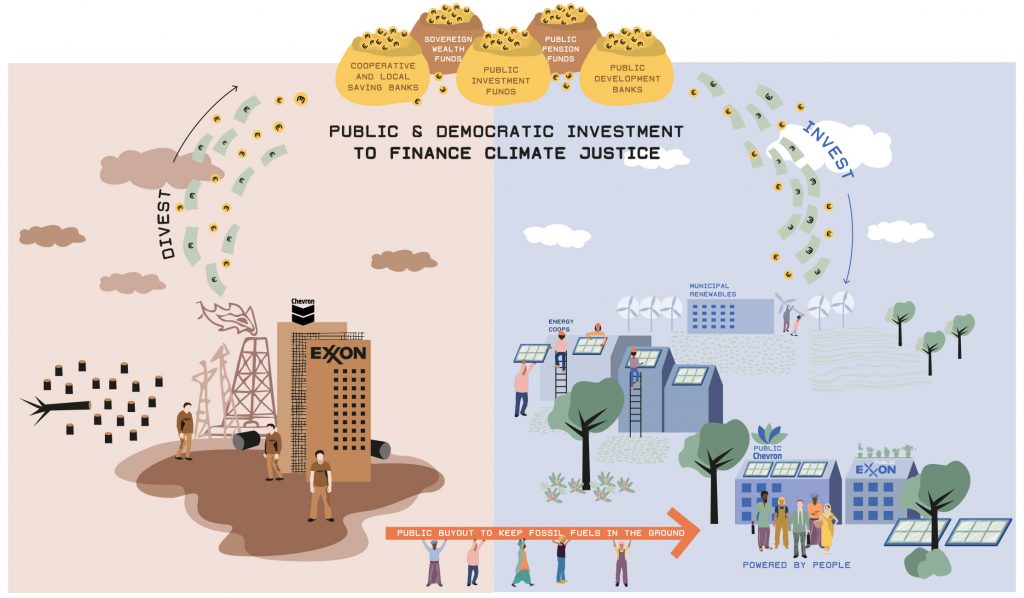

The most effective and timely way to untangle the paralyzing relationship between government and industry is through a federal buyout of the fossil fuel companies that control these noxious assets. In brief, the federal government would acquire 51 per cent or more of the shares of such major US-based, publicly traded fossil fuel companies as ExxonMobil, Chevron and ConocoPhillips. By controlling these companies’ decisions, the federal government would move away from profit-driven, short-sighted shareholder interest, winding down production and locking up fossil fuel reserves in the ground — all while deflating fossil fuel companies’ undue political influence.

To ensure that climate safety stays a priority for the government, as soon as these companies are in public hands a number of changes must take place. This include redefining their charters to reflect the end goal of declining fossil fuel production, decommissioning projects and, when appropriate, facilitating a just transition (e.g. by investing in wind and solar projects or other initiatives that align with a green transition framework). As a second step, the recently converted public companies must also adopt participatory and democratic procedures that give decision-making power to stakeholders, including a seat and voting rights at the board, along with the implementation of measures that promote transparency and accountability to the public.

We need to recognize that we have been relying mainly on services and products provided by private fossil fuel companies to meet people’s energy needs and that this did not come without sacrifices. On top of inevitable accidents, many dangerous spills were allowed to happen on grounds that it is more profitable to pay for damages later than to prevent them now, and owners walked away from numerous wells and sites leaving remediation and decommissioning procedures and costs to the next generation.4

This sorry record shows that we cannot transform fossil fuel producers quickly enough; instead, our best chance is for the government to intervene in the form of nationalization and democratization. If government controls fossil fuel reserves democratically, extraction decisions will not be made in lobbying wars and in closed-door negotiations. Instead, decisions will centre on what really matters: emissions, resource intensity, and how to mitigate social impacts on low-income people, workers and communities. If we do not have the luxury of time and carbon budgets to give fossil fuel producers another chance to serve their customers’ best interests, the re- maining option is to become their bosses.

Unusual suspect: the Federal Reserve Bank’s role in mitigating climate change

Many analysts fear that the fossil fuel sector could be instigating the next financial crisis. In 2008, the US economy neared collapse when the mortgage market was overestimated. The same peril is mounting again, but this time in the shape of fossil fuel reserves and infrastructure that will no longer be needed — and so will not provide the expected financial returns. Fear of stranded fossil fuel assets has grown among financial regulators and investors. As nations committed to limiting temperature increases to ‘well-below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursu[ing] efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels’6, environmental regulations across the world have since tightened and civil society has started to revoke some of these organizations’ social licence through growing lawsuits, divestment movements and protests.

Estimates on the size of the fossil fuel threat in the global financial market vary widely. The highest number so far, presented by CitiGroup in 2015, is US$100 trillion7 — significantly more than the total losses from the 2008 financial crisis.8 Mirroring the previous crisis, both the responsible sector and millions of workers and companies outside the fossil fuel market would feel the pain. Bank of England (BoE) Governor Mark Carney contends that up to one-third of global wealth may be at risk due to fossil fuel-stranded assets,9 including that of pension funds that hold the retirement of teachers, veterans and nurses.

As it did in 2008, the US central bank, better known as the Federal Reserve Bank (the ‘Fed’), could play a crucial role in diffusing this impending catastrophe, this time in a preventive and positive way. The century-old agency has under its current functions to ensure the stability of the financial system and minimize systemic risks through active monitoring and engagement.10 The systemic threat imposed by irresponsible fossil fuel companies should be enough to trigger the Fed to intervene now. Other central banks around the world have already started to act on their responsibility to better understand and try to avoid a financial crisis caused by the fossil fuel industry’s stranded assets. The most vocal among central banks is the BoE. Since 2015, when BoE Governor Carney alarmed investors in the famous speech ‘Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon’, the bank has started a research agenda, a working group, and a coalition with several other central banks to clarify their role in addressing systemic environmental risks.11

Besides anticipating and managing threats to the financial system, the Fed wields the monetary power needed to pull off a federal buyout of the six big private fossil fuel companies without burdening taxpayers. The agen- cy’s sovereignty enables it literally to create money out of thin air. One monetary tool is ‘quantitative easing’ (QE): ‘quantitative’ in relation to the large amount of money that can be created and ‘easing’ in reference to the ultimate goal of the process, which is to help the economy through money injection. This tool was used during the latest financial crisis by the Fed, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and other central banks. In the US alone, the Fed created over US$3.5 trillion between 2008 and 2014 to bail out bankers and financial institutions — without materializing the traditional concern of runaway inflation.12 Now it is time for the Fed to act on behalf of people and the planet, again without the worries of fuelling inflation as there is still plenty of room in the United States for new money. This includes more than seven per cent of the population who still cannot find full-time jobs, combined with the urgent need for new green infra- structure investment to allow us to transition away from fossil fuels in the next decade.13 Furthermore, due to the nature of the buyout, it is unlikely that large portions of the money would ever touch the real economy as fossil fuel investors, such as pension funds, would use the cash influx to seek new investment opportunities. For the remaining fossil fuel investors, further risks of inflation could be deterred if the buyout plan is designed in a way that encourages them not to cash out their financial gains, but rather to rollover the money, tax-free, to renewable energy stocks or bonds to help spur the energy transition.

Strategic breakthroughs and outcomes of a federal buyout

The potential benefits of a QE-financed federal buyout are manifold. Besides neutralizing fossil fuel opposition to climate action, which few other meaningful supply-side proposals could do, a federal buyout has two other selling points. It would leapfrog critical shortcomings of standard supply-side initiatives — namely, lock-in infrastructure and green paradox — and clear a path for a just energy transition for fossil fuel workers and communities.

Leapfrogging lock-in infrastructure and the green paradox

Once certain infrastructure is in place, decrease in demand and other changes in market conditions alone will not stop production. This so- called infrastructure lock-in particularly dogs the fossil fuel industry, where the bulk of investment capital is sunk in the project’s first years to build needed structures and facilities. Once infrastructure is in place, ‘producers will ignore sunk costs and continue to produce as long as the market price is sufficient to cover the marginal cost (but not the average cost) of production’.14 Both well-established infrastructure and new projects are subject to infrastructure lock-ins. Investors might, for instance, invest in a new coal mine if convinced that ‘the short-term value of the profits that can be earned under current policy settings … [exceed] the long-term (risk-adjusted) cost of detrimental policy change’.15 Policy uncertainty thus reinforces this climate-hostile rationale.

The green paradox occurs when companies accelerate fossil fuel production in anticipation of future policy and market trends.16 Fearing asset devaluation, producers speed up extraction and production to cash out profit as quickly as possible. Like infrastructure lock-in, the green paradox also invites greenhouse gas emissions and severely diminishes our chances to plan and implement an orderly transition to renewables in two ways. First, it shortens the already scarce time we have left to decrease fossil fuel production and ramp up renewable infrastructure. Second, it deepens fossil fuel dependency as people continue to buy carbon-intensive assets, such as cars and far-away homes, without taking climate change impacts — physical and financial — into consideration.17

Credit: Carla Skandier

A federal buyout of fossil fuel companies, which would cover their domestic assets and operations, would skirt both infrastructure lock-ins and the green paradox. That is because fossil fuel producers would no longer financially benefit from short-, medium- or long-term fossil fuel production. Shortening the renewable energy investment gap, a federal takeover would also send a clear signal that the future is renewable.

The proposal’s true game-changer, however, is making climate action attractive to fossil fuel companies facing endless negotiation and litigation. As an alternative to ‘produce all now or lose most later’ (catchwords often used to tar climate policies), a federal buyout affords a reasonable and prompt exit option to fossil fuel companies by compensating investors without having to keep up production. At the same time, the process to determine the amount of compensation needs to be democratic in order to avoid rewarding bad actors. Any evaluation process should exclude assets that have been wrongfully counted as valuable and take into account the environmental damage these fossil fuel companies have caused as well as the profits and public guarantees they have extracted.

Clearing the path for a just transition for fossil fuel workers and communities

A democratically designed buyout proposal also potentially allows govern- ment to devise and activate a comprehensive, orderly transition plan that marries fossil fuel decommissioning with renewable capacity rise, all while leaving no dependent worker or community behind.

As it is now, big private energy companies treat workers and communities as the inevitable collateral damage of misguided judgements and maxi- mization of private interests. General Electric, for example, in late 2017 announced 12,000 job cuts in its fossil fuel-heavy power department, a decision made to right size the business amidst a decline in fossil fuel use. Just two years earlier, the company had decided to double its inventory of large coal turbines.18

This callous approach is not only immoral, it could also undermine a successful transition to clean energy. Often, when company towns vie to remain standing, last-minute decisions set off a wave of job losses and revenue decline that can damage or ruin the community’s structure. From a climate perspective, throwing away communities translates into ‘empty houses, half-empty schools, roads, hospitals, public buildings, etc., [that we must] rebuild in a different location, with all the associated carbon costs’.19

Federal government’s role should be securing fossil fuel reserves through a federal buyout of the domestic assets and operations of these major companies and implementing a cohesive, orderly and just transition plan that supports, builds on and lifts workers and communities along the way. And that plan must leave room for those directly affected to participate in and guide a future away from the extractive economy.

When other governments for which the same premises hold true – namely the existence of a significant privately owned, publicly traded energy sector that works against climate action and a strong central banking system – would also democratically direct their central banks to buy out the fossil fuel companies in their countries, then fossil fuels could be kept in the ground at a much faster pace.

Workers’ new roles and meaning

An undeniable consequence of de-carbonization will be job losses in the fossil fuel sector. The good news is that the energy transition requires a lot of workers. As estimated by economist Robert Pollin and others in 2014, an investment of US$200 billion annually in renewable energy and energy efficiency could create 4.2 million jobs in the US, a net gain of 2.7 million when jobs lost from the fossil fuel sector are counted.20 The bad news is that matching new jobs and displaced workers will not be simple. Many jobs will appear in new locations and require new expertise.

That said, creating a comprehensive, coordinated federal transition plan from the get-go can prevent unnecessary and permanent disruption of fossil fuel workers and their families. Looking at lessons learned from coal communities in six countries, researchers concluded that failure to anticipate, accept and prepare for the transition is a key difference between securing workers a continuous path in the workforce and falling into long- term unemployment.21

The transition plan’s first goal must be to avoid large-scale, last-minute layoffs. Quite simply, workers leaving current carbon-intensive work need a safe passage into jobs with a future. The way could be paved with a clear climate policy so young adults could compare the odds of specializing in various fossil fuel sectors and workers already employed by the industry could get trained for new roles. But the government must also adopt ‘emer- gency measures’ in anticipation of the disruptive impacts the transition will inevitably have on some workers and their families. A standard income for workers and families, for instance, would enable them to weather surprises or changes without compromising their health and the assets built by their hard work. Other forward-looking policies, such as relocation assistance and counselling, can also be considered.22

The government could guarantee full employment to workers, stabilizing their income during the transition and preserving the meaning that employment provides to life for many. Meaningful labour is particularly

important for fossil fuel workers, whose jobs provide a living and also an inheritance maintained over generations. In that vein, government should also find ways to keep at least some workers in the ‘same’ industry, albeit with an evolved purpose and vision. Instead of coal mining, for instance, some former miners could continue reporting to the same locations, with the same company, to revitalize the compromised land and waters for the benefit of their communities and neighbours. After all, workers who helped build and maintain fossil fuel projects are often best qualified to decommission facilities, clean up and otherwise revitalize old sites.

Communities’ diversification and economic renewal

In many cases, communities across the country will need to diversify and renew their economy. No one knows better than each community how to determine and evaluate what comes next. Local people are the experts at identifying their historical, cultural and available capacity. Anchor institu- tions such as hospitals, universities and public departments have a unique opportunity and powerful procurement capacity to lift their communities and people both sooner and later.

But what will happen in the many rural communities that have depended heavily on the fossil fuel industry but lack anchor institutions or alternative industries to support their transition? Here, government must intervene to help communities feeling cut off at the knees through a robust plan to stabilize their economic base. One of many options is to identify and recognize affected communities as ‘Opportunity Zones’, an economic development tool created in 2017 to spur economic development and job creation in distressed communities.23

Another suggestion builds on the idea that fossil fuel companies, now publicly owned and democratically controlled, could be transformed into ‘environmental revitalization’ enterprises. By way of example, with a lignite (brown coal) economy in full force in 1985, East Germany saw both production and workforce in the sector decline by almost two-thirds within a decade.24 The city of Leipzig alone, the region’s industrial centre, lost 100,000 people over a decade.

Looking to provide a brighter future to the region, the government, through the federally owned Lausitz and Middle Germany Mining Administrative Company (LMBV), started the revitalization process of former open mines (employing 20,000 people along the way).25 The result: the region, the ‘largest artificial lakeland’ in Europe, is today a tourist destination with 26 lakes providing a variety of recreational activities, including canoeing, kayaking, scuba diving, triathlon competitions, restaurants and party spaces.26 Although the region’s redevelopment is more complex than exposed here, the revitalization of ‘once one of the dirtiest areas in East Germany’ into a pristine landscape of ‘soaring pine forests, glistening lakes and immaculate asphalt cycle paths’, shows that providing old fossil fuel communities a new, better meaning is possible.

Conclusion: 51 per cent solution for the climate crisis

There is no easy fix that would free us from the climate mess we are in, but a federal and democratic takeover of major fossil fuel companies in the first links of the supply chain could turn the tide. If fossil fuel reserves were under popular control, their future could be decided for and by the people, instead of by profit-driven, short-sighted shareholders. Only democratic government can ensure the planned wind down of fossil fuel production in accordance with climate safety goals. With room for private profit cut out of fossil fuel extraction and production, the powerful entrenched opposition of the energy sector would crumble. And with government and fossil fuel industry interests untangled, complementary climate initiatives could be adopted and implemented – so could a cohesive, orderly and just transition plan that leaves no one behind. The transition to a sustainable, renewable, non-extractive economy requires nothing less.

This chapter is adapted from the ‘Quantitative Easing for the Planet’ article by Carla Santos Skandier originally published in September 2018 in the Taking climate action to the next level report by The Next System Project, an initiative of The Democracy Collaborative, and available at thenextsystem.org/climateaction.

About the author

Carla Santos Skandier is a Senior Policy Associate with the Next System Project at The Democracy Collaborative. She holds a Juris Doctor degree and an environmental specialization degree from Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, and a Master’s in Climate and Energy Law & Policy from Vermont Law School. Since 2015, Carla has been focusing her work on promoting systemic solutions that take into account the political, economic, social and environ- mental aspects of the climate threat.

هوامش

1 Although from 2012, the study’s conclusions remain true today. Anthony Lopez et al. (2012) ’U.S. Renewable Energy Technical Potentials: A GIS-Based Analysis’, National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

2 Federal Reserve (n.d.) Home / Monetary Policy / Credit and Liquidity Programs and the Balance Sheet. Available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_openmarketops.htm (retrieved 3 August 2018).

3 Muttitt, G. (2016) ’The Sky’s Limit: Why the Paris Climate goals require a managed decline of fossil fuel production’, Oil Change International.

4 Colorado alone has 260 ‘orphan’ sites in the shape of inactive oil and gas wells. Elliott, D. (2018) ‘Colorado to accelerate cleanup of ‘orphaned’ oil, gas wells’, Associated Press, 19 July. Available at: https://apnews.com/b10ea1ccbca9425abac258aff389b0f4/Colorado-to-accelerate-clean- up-of-’orphaned’-oil,-gas-wells (retrieved 20 July 2018).

5 Carney, M. (2015) ’Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon’, speech given at Lloyd’s of London,

UK, 29 September; ‘The Price of Climate Change: Global Warming’s Impact on Portfolios’, Black- Rock, October. Available at: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/bii-pricing-climate-risk-international.pdf (retrieved 8 July 2018).

6 UNFCCC Paris Agreement (2015), article 2(1)(a).

7 Channel, J. et al. (2015) ‘Energy Darwinism II: Why a Low Carbon Future Doesn’t Have to Cost the

Earth’, CitiGroup.

8 Yoon, A. (2012) ‘Total Global Losses From Financial Crisis: $15 Trillion’, The Wall Street Journal,

1 October. Available at: https://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2012/10/01/total-global-losses-from-financial-crisis-15-trillion/ (retrieved 23 July 2018).

9 Of equity and fixed assets. Carney, M. (2015) ’Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon’, speech given

at Lloyd’s of London, UK, 29 September.

10 Federal Reserve Bank n.d.) About the Fed. Available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/about-

thefed.htm (retrieved 23 July 2018).

11 Bank of England (2017) ‘Quarterly Bulletin 2017 Q2’. Available at: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2017/the-banks-response-to-climate-change. pdf?la=en&hash=7DF676C781E5FAEE994C2A210A6B9EEE44879387 (retrieved 20 July 2018); Banque de France (n.d.) ‘Network for Greening the Financial System’. Available at: https://www. banque-france.fr/node/50628 (retrieved 20 July 2018).

12 Irwin, N. (2014) ’Quantitative Easing Is Ending. Here’s What It Did, in charts’, New York Times, 29 October. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/30/upshot/quantitative-easing-is-about-to-end-heres-what-it-did-in-seven-charts.html (retrieved 3 August 2018).

13 Data provided by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics for October 2018 when considering total unemployed plus total employed part time for economic reasons, and all persons marginally at- tached to the labor force. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018) Economic News Release / Table A-15. Alternative measures of labor underutilization. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/ empsit.t15.htm (retrieved 5 November 2018).

14 Green, F. and Denniss, R. (2018) ‘Cutting with both arms of the scissors: the economic and political case for restrictive supply-side climate policies’, Climatic Change. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2162-x.

15 Ibid.

16 Sinn, H.-W. (2012) The Green Paradox: A Supply-Side Approach to Global Warming. Cambridge:

MIT Press.

17 Seto, K. C. et al. (2016) ‘Carbon Lock-in: Types, Causes, and Policy Implications’, Annual Review

of Environment and Resources 41 (November).

18 Skandier, C. S. (2017) ‘When Companies Deny Climate Science Their Workers Pay’, Truthout, 28

December. Available at: https://truthout.org/articles/when-companies-deny-climate-science-their-workers-pay/ (retrieved 23 July 2018).

19 Alperovitz, G. et al. (2016) ‘Systemic Crisis and Systemic Change in the United States in the 21st

Century’, presented at ‘After Fossil Fuels: The New Economy’ conference, Oberlin, OH, 6-8

October.

20 Pollin, R. et al. (2014) ‘Green Growth: A US Program for Controlling Climate Change and Expand-

ing Job Opportunities’, Political Economy Research Institute and Center for American Progress.

21 Caldecott, B., Sartor, O. and Spencer, T. (2017) ‘Lessons from previous “Coal Transitions”

High-level Summary for Decision-makers’, IDDRI and Climate Strategies. Available at: https://www.iddri.org/sites/default/files/import/publications/coal_synthesisreport_v04.pdf

.

22 For more information see Green, F. (2018) ‘Transition Policy for Climate Change Mitigation: Who,

What, Why and How’. CCEP Working Paper 1805, May. The Crawford School of Public Policy

Australian National University.

23 Opportunity zones were added to the Tax Code by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. For more

information see Economic Innovation Group (n.d.) Opportunity Zones. Available at: https://eig.org/opportunityzones (retrieved 3 August 2018).

24 Herpich, P., Brawers, H. and Oei, P.-Y. (2018) ‘A historical case study of previous coal transitions

in Germany’, IDDRI and Climate Strategies.

25 Finch, M. (2017) ‘Urban life after coal: Leipzig’, Coal Transitions, 23 March. Available at:

https://coaltransitions.org/2017/03/23/urban-life-after-coal-leipzig/ (retrieved 27

July 2018).

26 Ibid. Also see Sullivan, P. (2016) ‘East Germany’s old mines transformed into new lake district’,

The Guardian, 17 September. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2016/sep/17/lusatian-lake-district-project-east-germany (retrieved 27 July 2018).

27 Ibid.