This essay is part of the book Public Finance for the Future We Want, you can find the entire collection of essays here.

Across the globe, wealth levels have been growing at a much faster pace than economies.1 Private wealth is also increasingly unequally shared. In the UK, a tenth of households own 45 per cent of the nation’s wealth, while the least wealthy half of all households own just 9 per cent.2

The growth in the pool of privately owned wealth has been fuelled by two main trends: 1) inflation in asset prices, especially property, in part the product of the post-2008 financial stimulus through ‘quantitative easing’; and 2) significant transfer of public wealth into private hands through the rolling privatization of industry, natural resources, land and social housing. In the UK, public wealth holdings – from profitable state-owned enter- prises like the Land Registry and Ordnance Survey to the land and property portfolios owned by local authorities and public institutions like the NHS – account today for roughly a tenth of total wealth, a post-war low.3 What is left of the ‘family silver’ is insufficient to offset national levels of debt, leaving the UK as one of a handful of rich countries with a deficit on the public finance balance sheet.

This growing imbalance between private and public wealth has been one of the key drivers of rising inequality. As the authors of the influential World Inequality Report have argued, the ‘very large transfers of public to private wealth’ since 1980 have been a key determinant of rising wealth concentrations. The decline in the level of net public wealth to the current negative level, according to the report, ‘limits the ability of governments to mitigate inequality’.4 Because of this, it will not be possible to make a serious dent in today’s heightened levels of inequality without policies that boost the public’s share of national wealth.

Wealth, and its distribution, matters. High levels of wealth can be used to boost wider social and economic security. Personal wealth can encourage well-being. Publicly owned wealth provides wider society with a stream of income while helping to offset national liabilities, such as the national debt or public sector pensions. Yet, little of the surge in wealth levels has been harnessed for the public good.

With the considerable returns from ownership (in the form of profits, rents and dividends) accruing disproportionately to the already rich, leaving the asset-poor even further behind, ever greater wealth concentration is built into today’s dominant model of capitalism. Whereas public wealth holds the promise of benefiting all in society, corporate and private wealth only benefit the few. The current wealth mountain offers a huge potential resource for building a better society. But to access those resources means tackling the growing problem of wealth concentration, managing national assets more effectively, and finding new ways of spreading capital ownership more widely.

In the last few months, the maldistribution of wealth has been creeping onto the political agenda. Once calls for higher taxes on wealth would have been dismissed as anti-rich and politically impractical; yet a growing band of unlikely voices are now calling for this resource to be taxed more heavily for the public good.5 Even The Times newspaper, not always a friend of such ideas, has dipped its toe into the debate with a recent call to ‘shift taxation from income to wealth’.6

Building the fund

Given the growing policy interest in the dangers of high concentrations of private wealth, wealth taxes represent the fairest and most effective way to finance a citizens’ wealth fund. The public tend to dislike wealth taxes, and distrust the way the revenue might be spent, even when they would not be directly affected by the tax. For this reason most rich countries have seen falls in the share of taxation coming from capital. But what if the proceeds of higher taxation on wealth – household and corporate – were ring- fenced and used directly for public benefit, thus by-passing the Treasury?

Financed by higher taxation on private wealth, a citizens’ wealth fund would provide a progressive and comprehensive route to getting more social value from existing assets, public, personal and corporate. Transparently managed and kept in trust for the public good, such a fund offers a powerful way of managing part of the national wealth, and could play a number of different roles in society: to store and build public assets and redistribute the gains from economic activity; or by more directly linking revenue and spending, it could help rebuild trust between state and citizens, thus boosting public support for social spending.

By giving all citizens a direct and equal stake in the returns from a grow- ing part of national economic activity, such funds would prove a powerful pro-equality instrument. The French economist Thomas Piketty has shown that the present economic model has a built-in systemic bias to inequality – a force, as he puts it, for ‘divergence’.7 Citizens’ wealth funds offer a way of creating a ‘new counter-force for convergence’, one which locks in a new bias to greater equality.8

To gain public support, such funds would have to continue to grow over time, and be a permanent and enduring part of the economic and social infrastructure in the UK. They would be owned directly by citizens, not the state, controlled by an independent Board of Guardians, with the support of a citizens’ advisory council.

Holding wealth in common

The idea that a share of national wealth be held in common has a long his- tory. Perhaps the earliest known debate about this principle came in Athens in 500 BC when the discovery of an exceptionally rich seam of silver led to a call for the windfall revenue to be distributed among all 30,000 citizens in a regular and equal cash payment as a citizens’ dividend. It was an idea that would have transformed the way wealth was shared in this Greek civilization. In the event, the Athenian Assembly voted against the revolutionary idea and instead used the bonus to expand the Athenian navy.

In 1797, the human rights campaigner Thomas Paine argued that the earth should be seen as the ‘common property of the human race’. In the twentieth century, the Nobel Laureate James Meade reinforced this idea of legitimate claims on natural and created wealth by calling for the greater socialization of private capital (including a portion of corporate profits) with the returns accruing to all citizens.

In recent times, scores of countries have pooled wealth through sovereign wealth funds, nearly all created from the proceeds of oil. However, few of them act as a progressive force, with most being unaccountable and secre- tive investment arms of the state.9

Perhaps the best-known example of the application of the principle of com- mon wealth is the creation of the permanent wealth fund in the US state of Alaska from the diversion of revenue from oil extraction. This fund has paid an equal annual dividend (from $1,000 to $3,500) to all citizens since the early 1980s. Known as the ‘third rail of Alaskan politics’, this audacious social experiment has proved hugely popular and, significantly, has helped ensure that Alaska has the lowest level of inequality of all US states.10

The UK could have followed this example when North Sea oil was discovered in the late 1970s. One proposal at the time was, as two Financial Times journalists put it in 1978, to ‘[g]ive [the revenue] to the people’.11 The proposal never materialized. Instead the revenue from this windfall gain was spent on current consumption, allowing governments to maintain spending levels while reducing tax rates. Today we greatly regret this classic example of short-term thinking.

The UK has in fact missed four major sources of ongoing revenue that could have been used to create a wealth fund (see Figure 1): the extraction of North Sea oil (approx. £200 billion), the sale of public land (approx. £400 billion), the sale of council housing (approx. £100 billion) and the privati- zation of state-owned enterprises (approx. £126 billion).

Financing a citizens’ wealth funds

Building a fund of any meaningful size today requires alternative sources of financing. There is a compelling case that the principal source should be increased taxation on wealth, creating a package that would help make reform of wealth taxation more politically palatable for more people. Additional options include the transfer of a range of existing commercial public assets into the fund such as existing publicly owned companies (e.g. Ordnance Survey or Land Registry); occasional one-off taxes (paid in shares) on windfall profits such as the Banker Bonus Tax; corporate payments for the use of personal data either structured as a tax or by creating a national data bank that could generate income through the ethical use of our data12; and the issue of a long-term bond, which can be thought of as a low- interest loan issued by the fund.

One of the most pro-equality approaches would be to establish a fund through the dilution of existing corporate ownership, with large companies making a modest annual share issue – say 0.5 per cent of the value of the company – with the new shares paid into the fund, up to a maximum of 10 per cent. Focusing on annual issuance of shares rather than tax makes the proposal more attractive to companies and investors13 while at the same time being more transformative economically and socially. Such an approach would gradually socialize part of the privately owned stock of capital to be used for explicit public benefit. By taking established stakes in companies, such a fund could help align the interests of society and business. A variation on this model was applied in Sweden in the 1980s through the creation of ‘wage-earner funds’, commonly known as the ‘Meidner Plan’, a bold, decade-long social experiment to further develop their model of social democracy, though one that eventually came to an end in the early 1990s.14

Inspired by work carried out at the New Economics Foundation15, the UK shadow chancellor John McDonnell proposed an ‘inclusive ownership fund’ aimed at giving workers a small ownership stake in the companies they work for. Funded by a proposed annual 1 per cent share transfer (up to a maximum of 10 per cent), the plan would entitle workers to a dividend payment up to a maximum of £500 a year. While under the scheme all businesses with over 250 employees would gradually become part-owned by employees, the proposal would have much less impact on the goals of spreading capital ownership, and its gains, across wider society, than would be the case with a fund that embraced all citizens.

Options for spending common funds

Creating such a citizens’ wealth fund does not offer a quick fix but a vision for a much more secure social future, paid for by a higher rate of national saving, and tapping into existing wealth pools. There are, of course, various options for spending the revenue from such funds. They could be used, for example, to pay for new areas of critical public spending, including new universal services such as child care and social care for the elderly. One possibility would be to use the fund to pay, as in Alaska, an annual citizens’ dividend. Although fundamentally long term, such funds would take time to establish. One recent study by authors from Friends Provident Foundation shows that, depending on the level of pay-in, a fund could grow to a level sufficient to boost key areas of social spending, including cash payments, after a decade.17 Over time, as the size of the fund grew to command a larger share of the economy, annual fund payouts could become more generous.

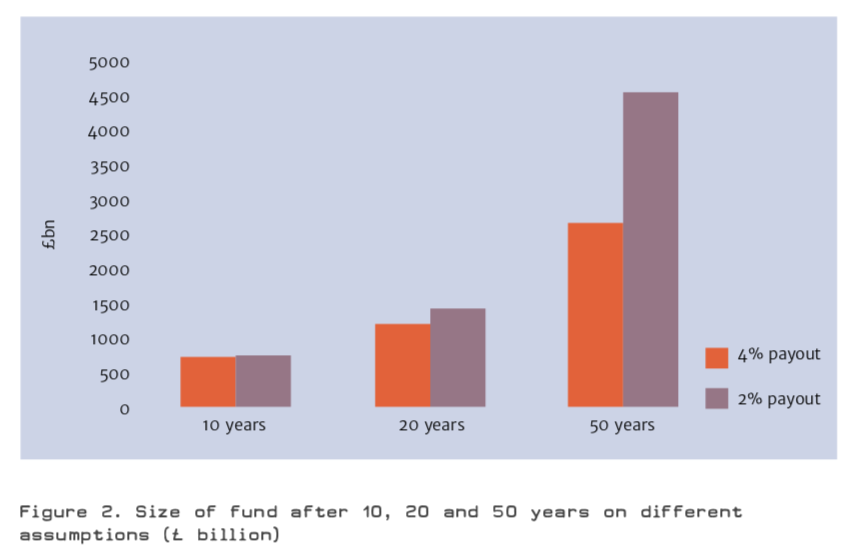

The Friends Provident Foundation study examined a mix of funding pro- posals, including an initial endowment of £100 billion for the citizens’ fund (from a mix of a long-term bond and the transfer of some existing public commercial assets) and an annual injection of £50 billion from additional taxation, nearly all on corporate and private wealth. The potential size of the fund achieved over different time horizons is shown in Figure 2.

While ambitious – and it would be possible to go for lower levels of funding and payout – the fund would accumulate over time. After 20 years it would have reached sufficient size to provide a modest annual dividend – of nearly £800 – to everyone. As it grows, and supported by wider changes in the tax or benefit system, it also has the potential to form the foundation of a more comprehensive basic income scheme.18

Creating a citizens’ wealth fund owned by all has a number of important merits. For the first time ever, all citizens would hold a direct and equal stake in economic success, with the fund automatically capturing a growing part of the gains from economic activity and distributing it equally. A fund would act as a counterforce to growing inter-generational inequities by slowly transferring a small portion of private wealth, which is disproportionately owned by older generations, into the permanent fund to be shared across future generations. A further strength is that this new economic instrument would help ensure that public assets would be better managed than they have been in the past.

Such funds could also play a key role in the reform of the current economic model. Provided they are managed at arm’s length from the state, they offer a new tool for social democracy and partial reform of corporate capitalism. In order to ensure public involvement in design, goals, funding and disbursement, a Citizens’ Council (similar to a Citizens’ Economic Council suggested by the Royal Society of Arts19) would be established to advise the Board. The Board of Guardians would include representatives from government, business, trade unions and the public. It would have overall responsibility for the financial viability of the fund, and produce a long-term evaluation every year of the projected future income and expenditure of the fund. These common funds represent a twenty-first century alternative to the top-down statism of old-style nationalization and the recent fashion for rampant privatization and uncontrolled markets, offering a new social contract among citizen, state and market.

Growing support

Of course, there would be political hurdles. Despite the vital need to do something about wealth inequality the public remain unsympathetic to higher levels of wealth taxation, from inheritance to capital gains tax, in large part because of the way such ideas have been demonized. This is personified in the popular names they have been given – who could possibly be for ‘death’ or ‘dementia’ taxes!

Today, there is at last some sign of a shift in the politics of wealth, including growing acknowledgement and support for social wealth funds with specific public purpose. As well as long-established funds such as the Texas Permanent School Fund, the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global or the Shetland Charitable Trust, new funds have been established in Australia and New Zealand. These funds have been capitalized in a wider variety of ways including land (Texas), oil extraction (Norway and Shetland), proceeds from privatization of state-owned enterprises (Australia) and government contributions (New Zealand). In the UK, a number of MPs across parties have acknowledged the potential of sovereign wealth funds. As former Conservative minister John Penrose has said: ‘a British Social Wealth Fund isn’t just feasible; it’s essential for capitalism’s future too. A fund would be socially just and generationally fair. And the time is now’.20

Alongside this political support, think-tanks from very different perspectives – from the Institute for Public Policy Project (IPPR)21 and the Royal Society of Arts22 to the Social Market Foundation23 along with the People’s Policy Project24 in the US – have called for wealth funds to be created with an interesting diversity of funding and spending options. The IPPR and Royal Society of Arts proposals aim to provide young people with a lump payment to enable them to meet the challenges of early adulthood and increase entrepreneurship whereas the Social Market Foundation proposal is concerned with ensuring public sector liabilities, both debt and pensions, are eliminated in the case of debt and fully funded in the case of pensions. The People’s Policy Project is the closest to the proposal presented here. It calls for an American social wealth fund equally owned by all Americans and paying out an annual universal basic dividend from the investment income.

The overseas evidence is that such a fund could gain significant public buy-in. By rebuilding the nation’s stock of depleted ‘family silver’, it would re-establish the importance of social wealth, boost the ratio of public to private capital, and tackle extreme wealth concentration. Legally ringfenced to prevent a Treasury ‘raid’, it would grow over time to play a sig- nificant social role. Such a model could work in countries of very different stages of economic development.

While the kind of model being advanced here is at the radical end of the possible range of proposals, it would offer a progressive way of managing part of the national wealth, provide a powerful new economic and social instrument that could command public support and build in a pro-equality bias that could transform the way we run the economy and society.

About the authors

Stewart Lansley is a visiting fellow at the University of Bristol. He is the co-author of Basic Income for All, From Desirability to Feasibility (with Howard Reed 2019) and the co-editor of It’s Basic Income: The global debate (with Amy Downes, 2018). He is also author of A Sharing Economy, How Social Wealth Funds Could Tackle Inequality (2016), Breadline Britain: The rise of mass poverty (with Joanna Mack, 2015), and The Cost of Inequality (2011).

Duncan McCann is a researcher at the New Economics Foundation interested in systemic and radical reform of the economy and the creation of a twenty-first century commons. He is co- author (with Stewart Lansley and Steve Schifferes) of Remodelling Capitalism: How social wealth funds can transform Britain. He is also part of the movements to reform money, author of Scotpound: A digital currency for the common good and co- author of the book People Powered Money; to reform land, writing about Common Ground Trusts and a founder of the Land Justice Network; and the digital economy, with recent publications including Blocking the Data Stalkers and Digital Self Control.

هوامش

1 Alvarado, F. et al. (2018) The World Inequality Report. World Inequality Lab.

2 Roberts, C. and Lawrence, M. (2017) Wealth in the twenty-first century. IPPR.

3 Lansley, S., McCann, D. and Schifferes, S. (2018) Remodelling Capitalism, How Social Wealth

Funds Could Transform Britain. City University, Friends Provident Foundation, May.

4 Alvarado, F. et al. (2018) The World Inequality Report. World Inequality Lab.

5 See, for example, IMF (2017) Fiscal Monitor: Tackling Inequality, October, p. 11; and Willets, D.

(2018) Baby boomers are going to have to pay more tax on their wealth to fund health and social

care. Resolution Foundation, 5 March.

6 Article by Philip Collins, 2018, on the website of The Times: Reforming capitalism is too risky for

Tories. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/reforming-capitalism-is-too-risky-for-tories-ktd-blrx9w

7 Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

8 Lansley, S. (2017) ‘Reversing the inequality spiral’, IPPR Progressive Review 24(2).

9 Lansley, S. (2016) A Sharing Economy. Policy Press, chapter 2.

10 Widerquist, K. (2013) ‘The Alaska Model, A Citizen’s Income in Practice’, Open Democracy, 24

August.

11 Brittan, S. and Riley, B. (1978) ‘A People’s Stake in North Sea Oil’, Lloyds Bank.

Review 128 (April): 1-18.

12 For more information, see: http://www.autonomyinstitute.org

13 For more information, see: http://autonomy.work/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Anonhuwswil-liams.pdf

14 Lansley, S. (2016) A Sharing Economy. Policy Press, chapter 4.

15 Lawrence, M., Pendleton, A. and Mahmoud, S. (2018) Cooperatives Unleashed: Doubling the size

of the UK’s Co-operative sector, New Economics Foundation.

16 Partington, R. (2018) How would Labour plan to give workers 10% stake in big firms work?, The

Guardian, 24 September. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/sep/24/how-would-la-bour-plan-to-give-workers-10-stake-in-big-firms-work

17 Lansley, S., McCann, D. and Schifferes, S. (2018) Remodelling Capitalism, How Social Wealth Funds Could Transform Britain. City University, Friends Provident Foundation, May.

18 See Lansley, S. and Reed, H. Basic Income for All: From Desirability to Feasibility, Compass, 2019.

19 Patel, R., Gibbon, K. and Greenham, T. (2017) Building a Public Culture of Economics. Royal

Society of Arts.

20 Blog by Duncan McCann and Stewart Lansley, 2018, on the website of Verso Books: Rethink-

ing Wealth: it’s time to create the UK’s first Citizen’s Wealth Fund. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3883-rethinking-wealth-it-s-time-to-create-the-uk-s-first-citizen-s-wealth-fund

21 Roberts, C. and Lawrence, M. (2018) Our Common Wealth: A Citizens’ Wealth Fund for the UK. IPPR, April. https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/our-common-wealth

22 Painter, A., Thorold J. and Cooke, J. (2018) Pathways to a Universal Basic Income. RSA.

23 Penrose, J. (2016) The Great Rebalancing: A sovereign wealth fund to make the UK’s economy

the strongest in the G20. Social Market Foundation. http://www.smf.co.uk/publications/the-great-rebalancing-a-sovereign-wealth-fund-to-make-the-uks-economy-the-strongest-in-the-g20/

24 Bruenig, M. ( 2017) Social Wealth Fund for America. People’s Policy Project. https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/SocialWealthFund.pdf