Housing in Kiev

Why don’t we have a place to live?

Alona Liasheva

This article is the first in a weekly series of three special edition longreads focusing on rural-urban inequalities in Ukraine. It is the outcome of a collaboration between TNI and the Commons: Journal of Social Criticism – an independent, internationally minded and progressive online and print journal from the Ukraine, publishing articles, interviews, reports, blogs and opinion pieces on current affairs in the Ukrainian, Russian and English languages.

A Russian language version of this article can be found .

With the end of Communism, cities across the former Soviet Union went through a range of transformations. As top-down urban planning came to a sudden end, cities – along with the entire post-Soviet region – embraced market-driven approaches based on liberal democratic ideology and integration into the global capitalist economic system. These transformations took place within a context of highly uneven development, with major differences between large cities on the one hand and smaller cities, towns, and villages on the other.

During the Soviet period, policy-makers at the national and regional level had aspired to relatively even development across geographical space, in contrast to the market-oriented spatial development in capitalist countries, which tended to exacerbate spatial inequalities. However, other social goals were often subordinated to this commitment to even development. As the Soviet regime’s planned economy failed to meet the basic needs of large segments of the population, people attempted to migrate to places where jobs, education, goods, and services were more readily available. In response, a number of oppressive regulations were imposed to prevent this kind of migration. These policies did lead to less spatial inequality than would otherwise have been expected, but they caused numerous social issues at the same time.

Among these regulations one of the most notorious was the propiska, or internal passport – a legal document and system that obliged people to remain in the jurisdiction where they were registered. This system prohibited free movement between rural and urban areas. Nevertheless, such movement continued to take place, and those who migrated without a valid propiska suffered ongoing social exclusion. When Soviet laws were changed or no longer enforced after the collapse of the Union, a spring was released and movement from rural to urban areas grew into a significant trend. As farms and rural factories ceased working, migration to bigger cities offered better prospects for people, even when the only work available there was informal or precarious. The restructuring of the economy, the concentration of emerging capital in bigger cities and the attendant impoverishment of the rural areas exacerbated this situation and created the conditions for massive migration to cities. This was the context in which contemporary post-Soviet cities initially developed.

One of the spheres most strongly affected by these changes was housing. The Soviet housing system had a number of contradictions, and new market contradictions emerged on top of these. As a result, housing in former Soviet countries came to be plagued by social problems. According to the Bloomberg Global City Housing Affordability Index, post-Soviet cities like Kiev, Moscow, St. Petersburg and Almaty are considered highly unaffordable, with Kiev ranked the second least affordable city for housing in the world. Though the indicators used for this ranking do not represent the full complexity of the situation, the index nonetheless points to certain trends, namely a deep housing crisis in post-Soviet cities. To better understand the mechanisms of change in the housing sphere in post-Soviet cities, this article will analyse housing in Kiev. It will address the factors which shaped Kiev’s transition to a market-based housing system after the end of the Soviet regime and the consequences of this process.

‘The city needs to develop’

Beginning in the early 2000s, Kiev and its metropolitan area became the main destination for people migrating within Ukraine, reflecting the uneven development of the country. People from rural areas, small towns, medium-sized cities and other big cities moved en masse to the capital city, mostly for employment and educational opportunities in for example the construction industry, the IT sector, or, especially for young people, higher education. Other big cities, like Odessa, Kharkiv and Lviv also experienced influxes of migration, but Kiev continues to be the most attractive destination. The housing stock in Kiev has increased as the population expanded, but, in spite of this, the scarcity of housing is a critical problem affecting urban dwellers. A closer look at Kiev’s growth helps to expose the reasons why so many Kievans have no place to live.

Over the last 26 years housing in Kiev has been expanding, not only physically but also as an economic sector and a financial instrument. Although the early 1990s were marked by a relative drop in the number of houses built compared with the 1980s, the absolute growth never ceased – not even during the economic crises of 2008 and 2014 which only slowed the relative pace of growth. As a result, the total housing stock in Kiev grew by 25% between 1995 and 2017. In addition to the constant housing growth in the inner city, the suburbs have also boomed. Nearby towns like Vishniovij and Irpen have expanded and continue to grow even faster than the city centre in relative terms.

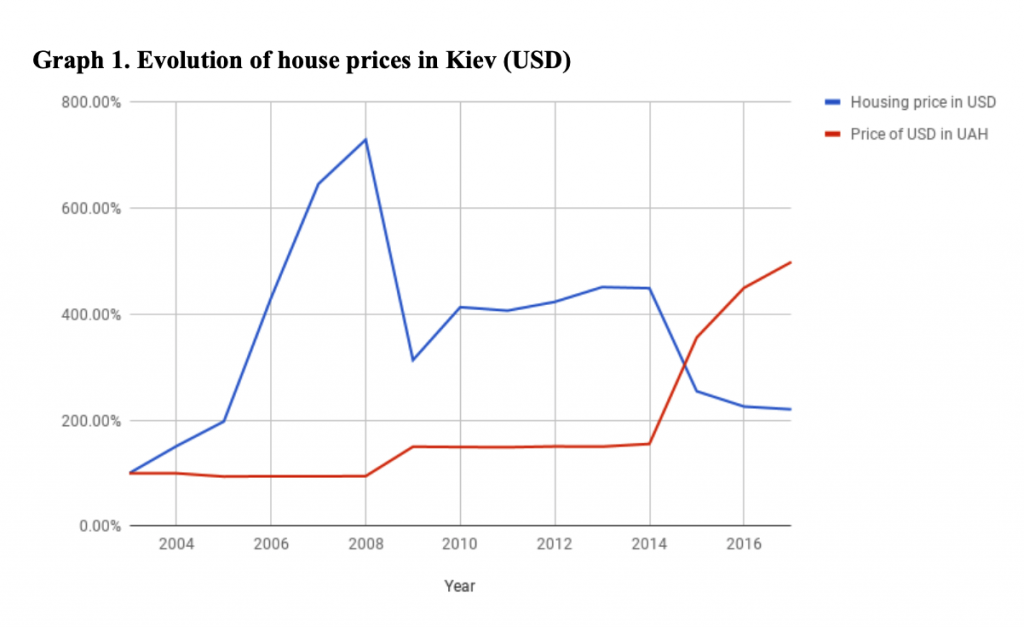

However, physical growth is only one part of the story, especially where housing expansion is accompanied by population growth. Viewing housing as an economic and financial sphere casts new light on the question of affordability. Examining price dynamics over recent decades shows how housing was transformed into a market commodity, which lost and gained value throughout the post-Soviet period. For instance, the graph below shows the change in the purchase price in USD of one square meter of newly built housing stock in Kiev, measured in January of every year and indexed against the price in 2003, and the changing rate of the USD in Ukrainian Hryvnia (UHD) over the same period.

Fuente: domik.ua

Graph 1 shows how the price in USD of newly built housing stock has changed, and how the value of USD compared to UAH has fluctuated since 2003. In spite of the gradual growth of the housing stock, the value of housing as a product has varied dramatically over time. After rapid growth in house prices throughout the 00’s, the recent drop in the value of UAH devalued housing substantially.

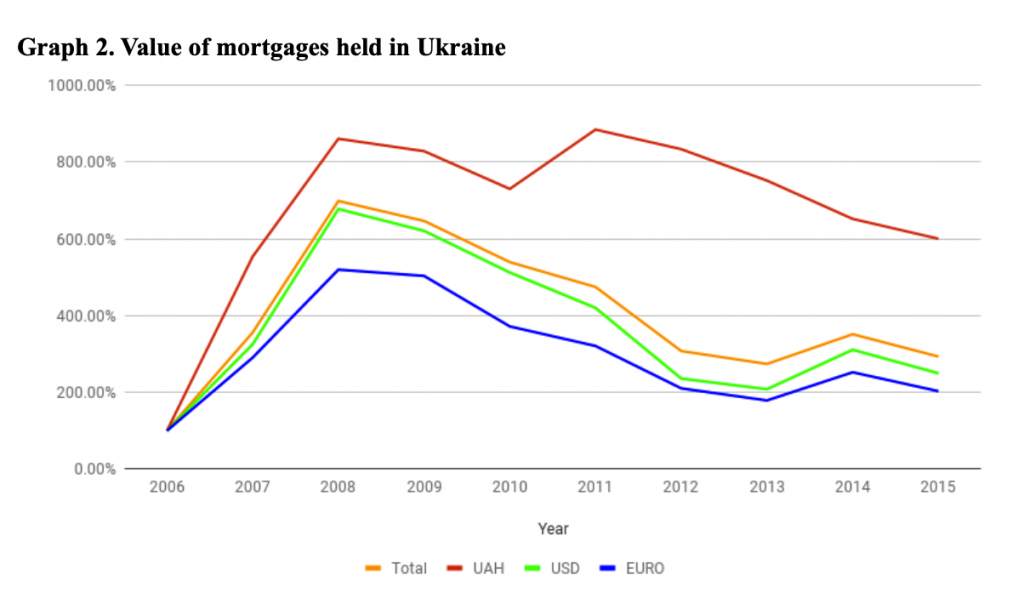

One of the reasons for these dramatic changes is that house building has been used as an instrument for financial speculation. It is possible to track the growing importance of this process by looking at mortgage loans provided. The graph below is based on data which show the value in UAH of mortgages held in Ukraine in USD, UAH and Euro. The graph is indexed against the value of mortgages in 2006.

Fuente: National Bank of Ukraine

The rapid growth in the total value of mortgages was interrupted only by the 2008 global financial crisis. In the pre-crisis period, mortgages were mostly issued in USD. However, in 2011 mortgages in UAH became more widespread, as mortgages in USD were no longer as widely available. In 2014, the country experienced renewed tumult, this time triggered by political factors which precipitated an economic crisis. This became an important factor in the development of the housing sphere in Kiev.

There were several turning points in the history of housing in Kiev, including: the arrival of international capital; the global financial crisis; and the political and economic crisis of 2014-2015. We can use these watershed moments to identify five periods in the history of housing in Kiev, punctuated by crashes or crises:

- Stagnation in the 1990s

- Gradual growth in the late 1990s and early 2000s

- Boom from 2000 to 2008

- Crash and recovery between 2009 and 2014

- New crash and construction boom in 2014 to 2018

Each period was tied, on the one hand, to an influx of capital into, or withdrawal of capital from, Ukraine more broadly and Kiev in particular. On the other hand, the strategies of a number of actors driving the growth on different scales – from international to urban – were also critical. For each period this article outlines the macroeconomic context, describes the crucial changes for the period, and shows which actors were advancing which interests and how.

But first… a bit of theory

An introduction to the basic theories grounding this research will be useful for what follows. These theories are based in traditions emerging from Northern America and Western Europe, so there is a need to adapt them to the distinctive local context of Ukraine in particular and post-socialist countries more generally.

The first corpus of theories consists of: circuits of capital, uneven geographical development and financialisation. Building on the Marxian logic of production of capital, David Harvey in his book ‘The Limits to Capital’ (among others), expounds a theoretical model of how capital circulates in order to overcome its inherent contradictions. Harvey describes three circuits of capital. The primary circuit occurs when the surplus value gets invested into technology, which results in over-accumulation. The secondary circuit happens with the flow of capital into the built environment, both the built environment for production and the built environment for consumption. The tertiary circuit is the flow of capital into the labour force – both through improvements of labour power though education and health, and through co-optation, integration and repression by various means including military ones. What role does housing play in these processes? Following Manuel Aalbers (‘Financialisation of housing: a political economy approach’) one can list several key interrelations:

- Housing is a result of production, so it is produced by labour to be sold. Moreover the production of housing sustains the construction industry. Thus it can play the role of a product in the primary circuit of capital;

- Housing is a means of wealth storage and it is a relatively stable one. As an exchangeable store of wealth, it facilitates the funding of effective demand when other sources dry up. In other words, housing becomes a tool to cope with over-accumulation, a crucial aspect of the secondary circuit of capital;

- Housing is a good which can make the labour force more productive, so it is also a means to improve labour power in the tertiary circuit of capital. Thus, housing often becomes an important part of the welfare state (e.g. social housing closer to workplaces can improve worker health and the flexibility of labour);

- Private housing is significant for capitalist ideology. It crystallizes the idea of private property as the ultimate and inevitable way of organising access to goods, as well as the ideals of the free market and wealth accumulation;

- Housing is considered to be a means of stimulating the economy through the mortgage system.1

The last characteristic makes housing an important part of the financialisation process. In his book Aalbers argues: “Financialisation is often defined [as] a pattern of accumulation in which profit-making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production”. He adds, “Due to the slowing down of the overall growth rate and the stagnation of the real economy, capitalism has become increasingly dependent on the growth of finance to enlarge money capital”. Aalbers argues that this process could be characterised as capital switching, and in fact constitutes a quaternary circuit of capital. Mortgage markets are not just enabling this process, they are driving it and are, moreover, replacing a range of state functions.

Spatial embeddedness is also critical to understanding these processes, especially the theorization on uneven development. Neil Smith, student and colleague of David Harvey, first elaborated the concept of uneven geographical development. However, he was not the first to recognise that Marx’s theory lacked sufficient analysis of how the capitalist system influences geographical space. The uneven distribution of capital over space was, for example, discussed by Rosa Luxemburg in ‘The Accumulation of Capital: A Contribution to an Economic Explanation of Imperialism’. Later, this theoretical work was elaborated in a variety of streams, perhaps the most significant one of which was world-systems analysis, which introduced the notions of core and periphery of the global socio-economic system. The main idea of this approach is that all the regions of the globe are interdependent, but unequally so: while some are exporting raw materials, low value added products and low skilled labour (periphery), others receive these goods and labour and use them to sustain high value added industries (core); semi-peripheries do both. This approach has a number of limitations, as it is often difficult to situate a specific country in such a scheme. Nevertheless, its strength lies in highlighting the uneven development of the global economy, which is highly important for understanding countries such as Ukraine.

Harvey and Smith are distinguished by their focus on urban space, rather than global space more broadly. In his dissertation and later book ‘Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space’, Neil Smith presents and justifies the importance of the notion of uneven geographical development by bringing together Marxism and academic geography and making Marxism ‘spatial’. For him space has evolved throughout the historical development of society, and social inequalities are reproduced in space. Space is inherently shaped by the social and economic world through which it is produced and the space constructed under capitalism therefore has specific characteristics emerging from the context of its formation.

To explain the characteristics of space generated under capitalism, Smith starts by revealing the next contradiction: “While social development leads to an increased emancipation from space in one direction, spatial fixity also becomes an increasingly vital underpinning to social development”. This means that, while capital is highly mobile, at the same time it accumulates in specific spaces, developing them for a time then moving on when other spaces become more attractive. Through the continual expansion of the capitalist system, new spaces are constantly opened or reopened in the process of capital flows. This is where uneven geographical development arises. Uneven geographical development is an outcome of constant investment and withdrawal of capital to and from specific spaces.

These theories give us the necessary instruments to describe the general logic of the transformation of the post-socialist cities that occurred with the integration of the region into the global economy. But they clearly lack an explicit treatment of the actors involved, as well as any exploration of their strategies and motivations. While these are significant questions for further investigation, this article will focus on showing the historical transformation of Kiev and its relationship to global socio-economic trends, from the 1990s onwards.

1. Stagnation in the 1990s

The period 1991-1999 was one of deep socio-economic stagnation in Ukraine. In 1999, national GDP was just 40.8% of what it was in 1990. The withdrawal of state investments from the national economy, fragmentation of the economy, and state capture led to de-industrialisation, the disappearance of whole industries, and the emergence of a service economy characterised by highly precarious working conditions and informality. Unsurprisingly, these processes led to massive impoverishment.

In the national economy of the 1990s, the first circuit of capital centred on manufacturing, while many other industries were dismantled, among them real estate and house construction. Nevertheless, this period could also be characterised as a time when the financial sphere and private banks, affiliated with finance and industrial groups, were established, with significant effects on the housing sphere in later periods.

The capital city of Kiev stagnated, along with the rest of the country. Factories were being closed with nothing, yet, to replace them apart from some enclaves of the service economy. The population was decreasing due to both out-migration and a decrease in the natural population growth rate. These factors had a direct influence on the housing sphere. Several processes which occurred in the 1990s set in motion trends that shaped subsequent periods:

Diminishing state-led development

As was the case almost everywhere in the post-Soviet region during the 1990s, housing in Kiev was built and distributed through state institutions or state-owned enterprises. However, public spending on housing dropped alongside other social spending in this period. Construction of housing in the 90s amounted to a drastically diminished and heavily financialised continuation of Soviet plans: the volume of new construction in Ukraine was halved between 1990 and 1995. However, this does not mean that development stopped altogether: several mikrorayons (microdistricts) were developed including Vygurivschyna-Troeshina in the North-East and Osokorki massiv in the South-East, as well as Teremki in the South-West and Belichi in the West of Kiev. This newly developed housing was still distributed through non-market mechanisms. Following the Soviet pattern of distribution, it often went to “nomenklatura” (people appointed to posts in government and industry under the Soviet Union) including employees of public administrative institutions, the police, army officers, etc.

Privatization of housing stock and establishment of the housing market

Mass privatization of housing was initiated by the passage of the law ‘On privatization of state housing stock’ in June 1992. Privatization was pushed by the state, and, unlike other post-socialist countries such as the Czech Republic, people were able to privatize their dwellings for free. The main reason for this was that the government saw housing not as a market asset but rather as a huge liability due to the high costs of maintaining and repairing existing stock. However, the decision to privatize housing for free may also have been motivated by an attempt to address the overall impoverishment of the population. It has resulted in Ukraine having an extremely high homeownership rate. According to the latest research by the State Statistics Service, only 1% of urban housing in Ukraine is publicly owned; most is privately owned by residents (93.3%) while the remainder – 5.7% – is rented out. The real numbers for rentals are likely to be higher, especially in Kiev, as the rental market remains very informal in Ukraine. Nonetheless, the point stands that renting is very expensive, accessible only to a small minority of people. As a consequence, many households are composed out of 2 – 3 generations living under one roof.

From the late 1990s, housing in Ukraine could be bought and sold officially, unlike during the Soviet period when the purchase of housing was part of the ‘shadow economy’.2 However, in the 1990s, individuals and families were still mainly buying homes for living purposes, not to use as an asset. It is only later that housing became a target for investment.

Privatization of state-owned housing enterprises

Ukraine, and especially Kiev, inherited from the Soviet Union a strong construction industry able to produce high rates of growth in housing construction if needed. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the majority of these construction companies were soon divided into different municipal enterprises, and the most profitable and promising assets were singled out and privatized.

No doubt, the best example of this trend is KievGorStroj (Kiev Urban Developer, KGS). The state institution GlavKievGorStroj (Main Kiev Urban Developer) became a state corporation and, later, in 1994, a state communal holding company. This meant that, while remaining a state enterprise, it could sell shares to private owners. Though the company changed its ownership structure and name, it did not change its upper level management. Volodymyr Polyachenko, who was the executive director of GlavKievGorStroj in 1979-82 and 1988-92, became the president of KievGorStroj in 1992 and kept this position until 2006. So the main housing development company in the city acted as an asset that helped the ‘red’ director to join the capitalist class and become an important political actor at both the city and national level.

From a cooperative to a private enterprise

Privatisation was not simply a top-down process, and it did not concern only State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), because the state was not the exclusive source from which housing was distributed. In 1988, the law ‘On Cooperation in USSR’ allowed the creation of cooperatives, which functioned as private enterprises producing and, more importantly, trading goods. In the 90s this became a way to start building housing with private investments. Some of the cooperatives later grew to become significant players on the market.

The 1990s in Kiev were characterized by stagnation as urban development was of no interest to the new state and therefore not properly financed through public funds, while, at the same time, the emerging capitalist class was not yet interested in real estate, focusing its attention mainly on the heavy industries. Nevertheless, the changes which occurred during this time had a strong influence on subsequent periods. That housing is and should be private property became an article of common sense, allowing the market to take over.

2. Gradual growth in the late 1990s and early 2000s

As a result of the privatisation and concentration of capital, two major Financial-Industrial Groups (FIGs), Dnepropetrovsk and Donetsk, were formed. The establishment of these particular blocks was determined by the reconfiguration of trade networks within and outside Ukraine. Such industrial blocks were part of the legacy of the USSR, but in the 90s their linkages with other nodes of the Soviet planned economy were broken, creating a need to look for new markets. These markets were found both within the country and internationally, gradually shaping the structure of the emerging capitalist economy. Some industries survived and expanded, some did not. Through this production and trade, capital was being accumulated.

Politically these processes were underpinned by the presidency, from 1994 to 2005, of Leonid Kuchma, whose regime and philosophy is popularly dubbed ‘Kuchmism’. Under his leadership the configuration of the ruling blocks stabilised and political power centralised, moving from the municipal and regional levels to the national, and from various government institutions to the president.

During this time, the political hierarchies which were disrupted by the fall of USSR were re-established, while at the same time the legal framework for commercial trade was created. These political transformations created the conditions for the privatisation of the SOEs controlled by the FIGs which rose to prominence by the end of Kuchma’s presidency. This was the period of the crystallization and strengthening of what is commonly called the oligarchic system. However, this process can be better understood as a hyper-concentration of capital which was the logical consequence of the rapid arrival of the market as a central force in Ukrainian society in the 90s, along with an unusually strong intersection between the newly emerged capitalist class, the old Soviet nomenklatura, and existing criminal groups. Under such conditions, real estate in Kiev became an attractive investment for the capital accumulated by these classes during the 1990s. State-led slow growth was thus transformed into market growth, led by a coalition of business and governmental elites.

There are several ways of directing capital flows into real estate. The biggest developer, KGS or KievGorStroj, was still mostly a public enterprise at the turn of the century, but, in the absence of adequate state funding, housing development was financed by attracting consumer investment into projects during the very early stages of their development. The widespread use of this mechanism had a number of consequences. Firstly, the risks of housing development were transferred to citizens so that if a developer went bankrupt, citizens who had invested their money based on the promise of future housing were left with nothing. Secondly, real-estate focused mainly on housing development, where it is easier to attract smaller investments, rather than on other types of built environment or infrastructure. Thirdly, this mechanism laid the ground for a highly chaotic urban development, as numerous ‘start-ups’ entered the market to compete with KGS, avoiding state regulations through corruption, and developing wherever land was available and without reference to a city-level plan.

Other strategies for profit-making were also employed. For example, another significant developer of that period, ZhitloInvestBud, was organized as a municipal company linked with multiple private firms – a mechanism for directing public funds to private actors. The company mostly undertook infrastructure projects and the building of social or relatively affordable housing in the peripheral zones of Kiev while channelling public money into private pockets. KAN Development Company organized a similar scheme, only in this case public funds paid for elite shopping malls in the downtown area. Besides having access to public funds, two co-owners of KAN also accumulated capital in the oil industry.

Following Kuchma’s example, Oleksandr Omelchenko, mayor of Kiev from 1999 until 2006, established systems that laid the political groundwork for the subsequent development of the housing sphere in Kiev. Omelchenko’s career took off in the building industry during the Soviet period and he was therefore closely networked with and patronized by the elites who captured the Ukrainian state. These connections allowed him to establish a development regime in Kiev which was profitable for his allies. His popular nickname in Kiev, ‘the builder,’ speaks for itself.

In this period, a powerful coalition of actors pushing for growth was established in the city, including a public-private merger and a strong intersection between the national and local levels of governance. Still, at this time, the involvement of the banking sector, and most significantly the international banking sector, in housing was minimal. Seeing no hope for high returns in housing, banking was focused instead on commercial real estate and elite housing, and on money laundering.

3. Boom in 2000s-2008

In the first years of the 21st century the Ukrainian economy began internationalizing, especially after Viktor Yushchenko came to power following the “Orange Revolution” uprising. Like all senior politicians in the country at the time, he protected economic elites. However, in comparison with other political actors Yushchenko was more open towards international, and especially Western, capital. His policy of openness was made possible by the fact that he relied politically on “second-tier” capitalists, who had a smaller stake in isolating the country from foreign competitors, as well as on importers, who stood to benefit from greater internationalization of Ukraine’s economy. At the same time the presidential campaign of 2004 unleashed the growth of voter incomes as a political tool; one of the key elements here was allowing increased imports of cheap consumer goods in order to raise the ‘standard of living’. Much more importantly, foreign capital began operating within Ukraine on a massive scale during this period. Although a number of foreign banks entered Ukraine, it was domestic banks that took the lead. Having low reserves they started borrowing on the international market and providing loans in Ukraine at inflated interest rates. This strongly contributed to the “dollarization”3 of the economy. The National Bank of Ukraine created the perfect conditions for this to happen by informally pegging the Ukrainian currency to the USD. As a consequence, private financial capital fuelled the economy throughout this period.

These changes in the Ukrainian economy, its short-lived growth and the crisis which followed, had a major impact on the city of Kiev. Firstly, the population of Kiev increased significantly during this time. This was mainly as a result of internal migration to Kiev and other major cities from rural areas and smaller cities within Ukraine. In 2002 the officially registered population of Kiev was 2,611,327 while in 2009 it reached 2,765,531, an increase of 5.91% in just seven years. To compare, in the previous seven years (1995-2002) the population of the city decreased by 1.23%. This dramatic growth was a result of investments coming into the country, and concentrating in the capital city.

Secondly, the intensive housing growth which had started in 1999-2000 continued in this period: between 8,000 – 14,000 new apartments were built per year. By comparison, in 1998 just 5.5 thousand apartments were constructed. These figures also do not include the suburbs of Kiev, which became veritable playgrounds for housing developers. This growth was interrupted only briefly by the recession of 2005, from which the market quickly recovered.

Thirdly, house prices in Kiev skyrocketed alongside the rapid growth of housing stock. Between 2003 and 2008, prices for newly built housing in Kiev increased 7.3 times. This was a general trend in Ukraine, but Kiev led in terms of absolute figures.

Finally, the boom is also reflected in the increasing number of developers in the city. If in the previous period KGS was the biggest player, with smaller developers occupying niches left vacant by KGS rather than competing with the behemoth directly, after 2003 the total number of developers mushroomed. The housing boom was going hand in hand with the commodification of land and the emergence of a new type of housing finance.

Land commodification

During the 1990s, development in the city proceeded mainly by filling in ‘pockets’ that had been left vacant or less developed by the previous plan – mainly in the Southern part of the Left Bank neighbourhood. As growth itself had slowed down drastically in this period, there was no need to modify the existing plan. However the rapid growth in the early 2000s, both of the city itself and of real estate, required the development of a new plan. This plan was adopted in 2002 with a planning horizon until 2020, and laid the groundwork for land commodification. Although land in Kiev remained officially a public good belonging, on paper, to the community there are numerous ways in which it is becoming a means of profit extraction.

First of all, the allocation of land plots for building purposes is a costly and extremely non-transparent process. Land for housing development in Ukraine cannot be sold, but only rented/leased by city councils. This makes the municipality dependent on the rental income, and makes bureaucrats of municipal departments dependent on bribes from developers. This all makes the land allocation process prone to corruption. In the end, although the price of land might rise for the developer, this cost is automatically incorporated into the price of apartments, so all increases are ultimately borne by homebuyers.

However, the municipality is not the only authority responsible for distributing land in Ukraine. Many state institutions such as the army, hospitals, and universities were awarded large areas of land during Soviet times, and many have started using this for profit. A particular type of investment agreement was developed to facilitate this: the public body gives the land to the developer, in exchange for a certain number of apartments which are to be transferred to the employees of the institution. Unsurprisingly this mechanism is seriously abused by the upper management of many public bodies.

The most notorious period of land use and allocation was from 2006-2010, under mayor Leonid Chernovetskyi, also known as ‘Lyonia the Cosmonaut’ or Lyonia Kosmos, a nickname which he received after one of his eccentric statements that he was going to fly into space with his cat. However, the only space exploration mission that he embarked on during his term was one to explore spaces in Kiev where land could be allocated for business.

Chernovetskyi was elected in 2006 after allegedly bribing impoverished elderly voters with food. He is known for singing at rallies and has offered to auction off kisses. Although public figures openly speculated about the need for a medical examination to judge his (mental) fitness for office, Chernovetskyi was clearly not stupid. Being the founder and main shareholder of Pravex Bank (later sold to the Italian Intesa Sanpaolo Group) he was already a wealthy person when he took office. During his time in office allegations of corruption surfaced constantly, particularly in relation to land use and urban planning decisions.

These scandals led to snap mayoral and city council elections in 2008, but these resulted in his re-election. The flamboyant mayor was accused of arranging the sale of historical buildings in the city centre for a tiny fraction of their true value, as well as incompetent management more generally and insider sales of land and municipal companies. One of the main mechanisms used by Chernovetskyi was the creation of communal companies to manage municipal assets and resources, which he appointed to people close to him to lead. Under his rule it is estimated that up to 3,000 hectares of land in Kiev were misallocated and ‘lost’ by the city. His mayoral position was so advantageous and profitable for him that, despite winning a seat in the parliament, he decided to remain in the municipal government instead. The land use decisions that were made under the rule of Chernovetskyi and his ‘young team’ (moloda komanda, as he called his deputies in the council) were later incorporated into the new master plan for the city, which was intended to regulate land use up to 2025, but which was ultimately never adopted. One of the key arguments for developing a new plan was the large number of developments in the city not covered by the existing plan: rather than halting or reversing development projects, it was proposed to update the plan to incorporate these. The land decisions made during this period have had a serious impact on the current situation.

Apart from land use and urban planning decisions, Chernovetskyi implemented a kind of ‘asset-based welfare’ mechanism in Kiev. He claimed that lonely elderly people were sitting in their apartments, “asset-rich, but resource- poor”. The communal company called ‘Better Home’ was created in 2008 to help those elderly people, who had to sign a contract to transfer their apartments to the company after their death, in exchange for lifelong care. The company was closed in 2010 when Chernovetskyi himself fled the country.

In sum, during this period land became commodified through both official and semi-official pathways. As a consequence, land became one of the main links between developers and public bodies. Still, land was not privatized and did not become a full-scale commodity, which kept the financial sector away from land speculation by e.g. using it as a credit guarantee.

Financialisation without securitization

As the Ukrainian economy “opened up” it became a battlefield for international banks, and real estate was no exception. Data on mortgages is publicly available only from 2006 onwards, but even these limited numbers show the degree to which the housing boom depended on international investment in the Ukrainian financial system.

According to data obtained from the National Bank of Ukraine, between the beginning of 2006 and the end of 2007 the value of mortgage loans provided in Ukraine increased by 3.6 times, from 20.52 million UAH to 73.08 million UAH. During the next year, the figure almost doubled again, to 143.42 million UAH. It is important to note that the currency rate in these years was relatively stable. Mortgages in this period were completely dominated by USD: 76 – 84 % of all mortgage loans were provided in USD, while the rest were predominantly in UAH, with just 1-2% issued in Euros. The data analysed is national, but it can be assumed that the level of dollarization in Kiev, as the capital city, was even higher than the national average. Compared to other countries, the Ukrainian mortgage market was not very extensive, but its rapid development nonetheless attracted many international players. Several European banks entered the Ukrainian economy after 2004, offering loans in USD. Ukrainian banks, in order to compete, began taking loans from abroad and reselling them in Ukraine in USD. Thus, the vast majority of the Ukrainian mortgage system immediately before the global financial crisis of 2008 was operating in US dollars.

As in many other cases from the so-called global periphery, including post-Soviet and Latin American countries, the financialisation of housing did not incorporate the full range of financial instruments present in core countries. While in the USA or Western Europe the liquidity of the mortgage market was backed by a mechanism of securitisation – the withdrawal of assets (i.e. loans) from the balance sheet of an enterprise or bank and refinancing them through the issuance of securities by another financial institution – in many other countries, liquidity was created without complicated financial tools.

Regulation of the mortgage market in Ukraine accelerated around 2003 when the new Civil and Economic Codes were adopted, as well as a Law on Mortgages. In 2004, the State Mortgage Institution was created to enhance the mortgage market by issuing covered bonds (a type of security) for mortgage loans. However, this special-purpose vehicle never fully lived up to its role. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, the main regulatory laws were adopted significantly later than other countries, in 2005 and 2006 respectively (‘On Mortgage Lending, Transactions with Consolidated Mortgage Debt and Mortgage Certificates’ and ‘On Mortgage Bonds’). Secondly, the State Mortgage Institution was supposed to deal only with loans issued in UAH, while the mortgage market was dominated by loans issued in USD. Thirdly, there was no demand for the bonds issued by this institution, as Ukraine had (and still has) no institutional investors (insurance companies, private pension funds, etc.), and bonds for loans in UAH could not attract private or international institutional investors.

But, if securitization was not a factor, then what did fuel the housing boom? The liquidity required by the Ukrainian market was provided by the difference between local and international financial markets. The Ukrainian macro-economic environment before the crisis, characterised by high inflation and a de facto peg to the USD, gave rise to high risks for investors, but also to high potential returns. It was possible to borrow cheaply and lend money in Ukraine with a much higher interest rate. This kind of speculation provided massive liquidity in the housing market, eliminating the need for legally-complicated securitization.

Urban expansion in Ukraine between 2003 and 2008 was fuelled by international financial capital. As a result the ‘housing bubble’ became enormous: by the end of 2006 the Ukrainian real estate market was valued at 400% of the national GDP – the valuation for the USA at that time was ‘just’ 160%. Inevitably, social consequences followed. However, unlike in the United States for example, the main victims of the bursting of the housing bubble were not the lower classes who were, and are, largely cut off from home ownership in Ukraine and rely on either the private rental market or on recently-privatized apartments where several generations often share a single apartment. Rather, the main victims of this boom and bust were the middle class, which emerged in this period, but vanished almost entirely in the subsequent waves of crises.

Though this period is commonly described as a period of growth, insufficient attention is given to the highly unequal nature of this growth. As capital accumulated predominantly in urban areas, rural areas were not developed. On the contrary, apart from the towns and villages where the industries were still strong (e.g. Krivbas), rural areas lost both wealth and population. Mykhnenko and Swain in their article ‘Ukraine’s diverging space-economy: The Orange Revolution, post-soviet development models and regional trajectories’ explore how this process was rooted in spatial inequalities formed in Soviet times. Analysing the pattern of regional incomes between 1900 and 2007 they conclude: “Whereas one-third of Ukraine’s regions gained relative to the national average, two-thirds lost. The biggest losers were the two adjacent central Ukrainian regions of Chernigovskaya and Sumskaya. Broadly, central Ukraine, lacking industry and cross-border activities, experienced the largest relative decline under post-communism. The east and south performed better, but Kiev was the biggest gainer in terms of percentage point change (+168 per cent), while Sevastopol and AR Krym were the biggest gainers by rank”. These trends became especially apparent after the “Orange revolution” uprising.

4. Crash and recovery between 2009 and 2014

With the global financial crisis, investments that had flooded into Ukraine during the 00s were withdrawn rapidly. Ukrainian FIGs also experienced losses due to falling demand for their products on foreign markets and the sudden withdrawal of foreign financial capital from the Ukrainian economy.

Construction of new housing declined dramatically, though temporarily. According to the State Statistics Service of Ukraine 76.4 thousand square meters of housing was completed in urban areas in 2008. This already represented a slight decrease from 2007, when 77.37 thousand square metres were constructed. By 2009, this number fell to 51.63 thousand. Between the peak in 2007 and the depth of the crisis in 2009, the rate of housing construction in Ukraine decreased by 33%. The drop in house prices was even more dramatic: in 2008 the average purchase price per square meter for housing in Kiev was $2,777 while by 2009 this had fallen to just $1,194, a decrease of 57%.

In this situation, citizens bore the consequences of many risks taken during the boom, for example in cases where buyers had invested in apartments in very early stages of construction. This gave rise to a number of social conflicts. Many construction projects were not completed. In some cases citizens took matters into their own hands, even organising a new enterprise to complete construction. However, many others simply lost their investments, and the projects in which they had invested are still standing, half-finished and abandoned. In addition to this, however, mortgages had been issued for some of these apartments which never came into being, and were never paid back. While these conflicts should be resolved in court, the highly bureaucratised legal system means that many cases are still unresolved. At the same time it is important to highlight that unlike, for instance Spain, evictions in Ukraine never became widespread. In these conflicts courts mainly took the side of citizens. This is partially the result of norms in the legal system which protect residents, but also partially a consequence of widespread corruption, which allowed many residents to produce “proof” that they belonged to a group entitled to special legal and social protections (for example people with disabilities), even when this was not the case.

The consequences for the population could have been very dramatic, bringing the potential for social unrest. With presidential elections pending in 2010, the national government saw a strong need, on both economic and political grounds, to address the emerging “credit gap”. One key tool for doing this was strengthening connections with the IMF: between 2008 and 2010 Ukraine received the biggest IMF loan in its history. The loan of 14.4 billion USD also made Ukraine one of the biggest borrowers from the IMF. It contributed to stabilising the situation, at least for period of time and over several years following the bursting of the housing bubble, the market slowly recovered. Since 2008, a number of private domestic banks were recapitalised or declared bankrupt. This stabilised the economic environment, which enabled the mortgage market to revive, this time in Ukrainian Hryvnia, and with the kind of regulation of the mortgage market that was conspicuously lacking in the early 2000s. As a consequence, housing construction rebounded. Apart from this, there was also policy to stimulate real estate in 2009-2014, although this was not widely taken up: just several hundreds of young families were issued with a mortgage from public funds. Still, mostly due to significant state intervention in the monetary system, the mortgage market slightly revived and stimulated the real estate sector – between 2009 and 2014 house sale prices grew by 43%. Were it not for dramatic political changes, this could have continued. However, a number of significant political changes have had a major impact on housing in Kiev.

5. New crash and construction boom in 2014 – 2018

In the end of 2013 a wave of protests took place in Ukraine, triggered by the national government’s decision not to forge closer ties with the EU. Popularly known as the EuroMaidan, this mass social unrest led to the Ukrainian revolution of 2014. This uprising, the new elites who came into power after it, as well as the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the contemporaneous armed conflict in the East of the country, changed the socio-economic conditions dramatically. The Ukrainian economy was reoriented towards trade with Western countries, leading to economic restructuring that strengthened some FIGs while weakening others. The sudden withdrawal of capital from the country combined with liberal fiscal policies and a total lack of regulation of the exchange rate – the UAH has decline 3,5 times in value – led to the impoverishment of the population, including those who had been able to afford housing in the previous period.

These drastic changes in the socio-economic and political situation had a direct impact on housing in Kiev: real estate prices have dropped significantly in recent years. In the beginning of 2014, the average price for a square meter of newly built housing was 1,710 USD; in 2015 this was 970 USD, which fell to 860 USD and 840 USD in 2016 and 2017 respectively. As property became less profitable, the secondary market (sales of existing homes) froze while owners waited for better sale prices. This ‘freezing’, along with other factors, drove further expansion of the private rental market. The main reason for the collapse of house prices is the dramatic decline in the value of the UAH. Those whose salaries are paid in UAH have seen their real income fall dramatically, to the extent that they can no longer afford to purchase real estate.

For the groups whose income is tied to the dollar, the euro or even the rouble, housing became significantly more affordable in this period and they began ‘seizing the moment’. In previous periods, the income and savings that people had in foreign currencies, often in cash and kept at home, was not enough to allow them to enter the housing market; in 2014 the value of these savings grew sufficiently to allow people to purchase homes. However, this development exclusively affected people with a medium-high income: the poor did not have this level of savings to begin with and could not capitalize on these currency fluctuations, while the rich have other ways to secure their wealth, such as moving it to other countries with more stable economies and political situations. Nonetheless, this situation gave rise to an unexpected housing boom.

Apart from this, there are other reasons for the boom. Trust in banks was low even before the uprising, but when dozens of banks were shut down in 2014-15, real estate became the primary way to secure savings.

The boom is being financed through much the same mechanisms as the 2003-2008 boom: citizens fund construction at a very early stage, and often their money is actually used to finish a previous project. However, there is one significant difference from the previous boom. This time there is no supply of affordable mortgages so real estate is not just a sphere which helps capital to circulate, as in the previous boom. Now, it extracts money directly from citizens.

This transformation has been reflected in the growing trend of so-called ‘smart housing’. While previously a citizen could take out a mortgage in order to purchase a 2-3 room apartment, now, relying only on her personal savings or the proceeds from selling an apartment elsewhere, she can only afford 15 square meters or a place in a co-living space. For ‘elite’ housing the situation is different: there are fewer and fewer buyers available for these kinds of properties, and developers can no longer sell units far in advance but must continue advertising them even when the development is already nearly completed. One of the reasons why ‘elite’ housing still survives is the growing internationalisation of this sector. While foreign investors are purchasing properties in the skyscrapers of Kiev, many are purchasing these as investment properties, which they hope to rent or re-sell at a profit.

At the present moment, it seems unlikely that the Ukrainian national economy will suddenly begin growing expansively. This means that the current construction boom, financed as it is by the limited resource of citizens’ personal budgets, is precarious. When this money runs out, and if no other source of liquid capital appears to take its place, Kiev may see another bubble burst and another wave of optimistic investors who financed construction processes may find their savings stranded in unfinished buildings.

So why do we still have nowhere to live in Kiev and how do we get a place to live?

Given the intensive growth in housing stock over the last decade, and the rapid growth of the capital city, why are more and more young people living with their parents, not even able to rent a room in Kiev? Why are multiple families often found living together in a single apartment? Why are people unable to move to the city, even if they get a job or a place in the university? The popular answers to these questions often amount to nothing more than denouncing those who are ‘not able to become successful’ or are not ‘creative enough’ to solve their housing problem. But the historical perspective outlined above shows that the answer is more complicated. To put it shortly: housing in Kiev has become not a home, but “real estate”; not a shelter, but an asset. This new “asset” is being manipulated by local elites, together with international banks and institutions, which are using housing as a tool for capital circulation. And in this respect Kiev is no exception, but rather an example of a trend taking shape across post-Soviet cities.

In order to improve the situation in the housing sphere there is an urgent need for policy interventions in several socio-economic spheres, as well as changes in the political life of the country, including greater democratization.

Firstly, monetary policies explicitly oriented towards the creation of public funds for housing finance are required. In the current situation of a very weak supply of mortgages from private financial institutions, such state actors will meet no competition. Funds for these initiatives might come from two possible sources: taxation of large business and “de-offshorization” of the economy. These sorts of policies, however, would go against the interests of the FIGs, so they would be possible only with the general democratisation of the governing process.

Secondly, regulation of developers and construction companies is needed. If public funds for housing construction are made available but channelled into a housing sphere operated by several big players, they will line private pockets with public money rather than providing affordable housing for the people of Kiev. As the biggest players in the property development are networked with the public institutions and political parties, public, and maybe even international, oversight in the policy-making processes is required for effective and transparent policy-making. Moreover, the diversification of the housing development and construction sphere with public enterprises at different levels (national, regional and urban) would also democratize the sphere.

Thirdly, even if state-backed mortgages become available and skyrocketing house prices can be avoided, these sorts of finance mechanisms will still engage only part of society. So, there is a burning need for massive social housing programmes which will address the housing needs of those living in poverty. For Ukraine this category makes up nearly 60% of the total population. Establishing social housing programmes is very difficult to achieve at the national level, but with ongoing decentralisation reforms, cities and towns will gain more independence in policy-making. While there is a risk that decentralisation could further deepen regional inequality, as there is already mounting interest in and pressure for this kind of strategy, it might offer an opportunity for social movements and municipalities to ‘seize the moment’ to start housing programmes. If social-oriented housing programmes emerge in at least one place, it might be an example for others and provide citizens of other cities with leverage to argue for similar programmes in their locale. Ultimately, these local spaces can provide opportunities to test and learn about strategies that would hopefully be developed across the country, balancing responsiveness to local situations with a commitment to leaving no city or region – including rural areas – behind.

Finally, it is highly important to raise awareness in the society at large about housing rights as basic human rights. The way the housing sphere has evolved for decades has strongly influenced the way people think about housing. Dramatic housing inequalities, debt-driven housing finance and the transfer of risks to buyers and tenants are normalised, even among activists groups. Educational and cultural work is a necessary foundation for building a movement to reform the housing system in Ukraine, and to provide accessible housing for all.