This essay is part of the book El poder de las finanzas públicas para el futuro que deseamos, you can find the entire collection of essays .

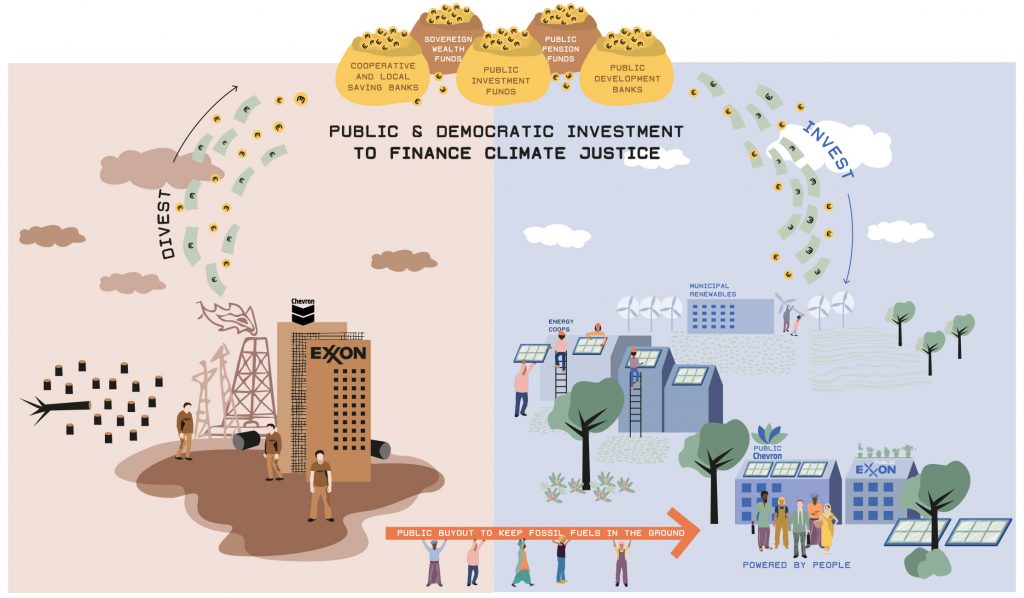

State-owned banks, cooperative and local savings banks, and public pension and investment funds have the potential to play a leading role in supporting a just climate transition, but a mixed record in achieving this goal. This chapter looks at how to shift public investment to ensure that it operates in the public interest, addressing climate change and social justice rather than simply prioritizing short-term profitability.

Despite regularly claiming new commitments to ‘green finance’, the biggest banks, pension and insurance funds still invest billions of dollars in the fossil fuel industry every year — including for the most extreme climate- damaging activities, such as exploiting tar sands oils and burning coal.1

Continuing to invest in fossil fuels goes against evidence about what needs to be done to tackle climate change. An estimated 80 per cent or more of the world’s known fossil fuel reserves need to remain in the ground if we are to have any chance of avoiding catastrophic consequences like sea level rise and melting glaciers.2

In place of fossil fuel finance, investment should be redirected towards renewable energy, cleaner industry and more sustainable agriculture, among other priorities. As our Financial System Change, not Climate Change report shows in more detail, the financial sector will not take the lead in bringing about that change.3 Shutting down fossil fuel financing requires public regulation, spurred on by public pressure from movements for divestment, energy transitions and greater equality. But it also requires new channels for public investment.

Public investment need not be governed according to the same short-term imperative for profitability that the private sector emphasizes, yet all too often public finance institutions fail to grapple with these differences. This chapter draws on a series of short examples of state-owned and local sav- ings banks, public finance institutions, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) to identify some key priorities that could encourage public investors to take the lead in forging a just and equitable climate transition.

State-owned and public banks

State-owned and public banks are particularly well-placed to invest in renewable energy and infrastructure to improve climate resilience. Private banks are often reluctant to finance renewable energy, to take just one example – either because international banking regulations (Basel III) can be a disincentive, or simply because they lack experience in how the financing of such projects works.

State-owned banks, by contrast, have already shown that they are prepared to finance a clean energy transition, especially if social and environmental goals are placed at the core of their mandate.4 Such banks are generally not constrained by demands for short-term profitability, so they have the capacity for taking a longer view and making decisions that support local economic development and environmental objectives.

In Germany, for example, the government-owned development bank KfW is a key funder of energy efficiency programmes, offering below market- rate loans (with special repayment arrangements) to small and medium- sized manufacturers. Approximately €3.5 billion was invested through this programme in 2016 alone.5 While that remains a small component of the state’s overall Energiewende (energy transition) plan – which has also come under attack in recent years – it remains a significant example of how public institutions aligned with public policy can start to reform the economy.

In the United States, the Bank of North Dakota (BND) showcases some of the advantages and limitations of state-owned banks. BND was originally developed to empower small farmers and support the local economy.6 During the financial crisis, it offered loans and liquidity to shore up local private banks. BND has been a useful vehicle for financing public infrastructure projects as well as paying annual dividends to the state treasury, enriching the public purse. It remains the only public bank in the US, although activist pressure originating from divestment movements, Occupy and marijuana legalization has led to feasibility studies in Oakland, San Francisco and Washington, DC, among other cities.7

BND takes full advantage of fractional reserve banking (lending beyond the level of cash-backed deposits) in its infrastructure investments. But while it could fund a transition to a cleaner economy – whether through municipal bond issues to finance public transport, or loans for renewable energy infrastructure – its actual practices reflect the priorities of the state’s financial elites, so it has seen assets poured into sustaining a fossil fuel-based economy. It even lent US$10 million to local law enforcement to subsidize the repression of indigenous communities at Standing Rock.8

State-owned banks in the global South – including national development banks – also have a mixed record. The Banco Popular y de Desarrollo Comunal in Costa Rica provides a positive example of the benefits of a ‘triple bottom line’ that integrates economic, social and environmental considerations. The country’s third largest bank, it is a hybrid between public ownership and a workers’ cooperative.9 Although environmentalism was not a central part of its original mandate, it has a growing portfolio of eco-credits, as well as financing for community energy cooperatives and efficiency schemes.

Public-like cooperative bank Banco Popular that is worker-owned and controlled. Credit: Luis Tamayo, Flickr, Licence CC BY-SA 2.0India’s National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development plays a key role in providing infrastructure, including the financing of irrigation systems, forest management, soil protection and flood protection schemes that are vital as the country adapts to the effects of climate change.10 It also finances smaller lenders (including cooperatives) in rural areas, while assuming part of the regulatory role in this sector.

As an accredited partner of the UN’s Green Climate Fund, now it can also channel international finance for climate-related activities – a model that could lead to greater local ownership of international finance than has traditionally been associated with climate and development funds passed through institutions like the World Bank. At the same time, it has been criticized for poorly managed and exploitative microcredit schemes.11

In other cases, state-owned banks like the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) and South Africa’s DBSA have been criticized for investing in projects that are harmful to local communities, or for ploughing significant funds into fossil fuel infrastructure.

Cooperatives and local savings banks

Cooperatives and local savings banks, some of which are owned by local government, remain an important part of the financial sector in many parts of Europe. These local banks and cooperatives generally have a public interest mandate that sets them apart from their larger commercial counterparts.12

While the structures of these local banks vary, they often involve employees, depositors, local politicians or civil society associations on their governing boards. Often, they are set up with an explicitly not-for-profit public mandate.13 French savings banks, for example, are required to dedicated half of their profits to social responsibility programmes, which are managed by representatives of social groups and politicians, as well as bank staff.14

In Germany, rules governing local savings banks (Sparkassen) vary according to region, but usually involve local lending obligations as well as a mandate to reinvest profits in achieving wider social objectives.15 This is reinforced through membership of the German Savings Bank Association (DSGV), which sets out common sustainability standards and social commitments.

The Sparkassen or cooperative banks (Genossenschaftsbanken) are key finan- ciers of local energy cooperatives, which account for almost 50 per cent of the country’s installed renewable energy capacity.16

German local savings banks typically arrange ‘civic financial participation’ schemes, creating a financial structure that allows individuals to directly invest in green energy projects which, in turn, come to meet their own consumption needs. Alongside individual investments, larger loans are often provided by Germany’s state development banks, such as KfW, which channel these funds through the local savings banks and cooperatives.17

Local savings banks are neither a panacea nor immune from the speculative impulses that characterize the big private banks. In Spain, savings banks that had been gradually liberalized to resemble the model of its commercial counterparts were hit particularly hard by the financial crisis of 2008. The intersection of deregulation and a governance structure that emphasized political appointees sowed the seeds of irresponsible property speculation and corruption.18

When they are well managed, though, local savings banks and cooperatives continue to offer a positive alternative for developing a greener economy. With ‘disruptive’ technologies (such as mobile financial services) likely to favour the decentralization of banking in the coming years, that sector has considerable scope to expand its influence – if banking regulations and other public policies allow.19

Public pensions, sovereign wealth funds and non-banking financial institutions

Public investment should also be channelled through non-banking financial institutions, which can include publicly owned companies and investment funds. In Bangladesh, for example, the publicly owned Infrastructure Development Company Limited helped to install more than three million solar home systems in rural areas between 2003 and 2014, bringing power to 13 million new users.20 It did so by providing capital to private partner organizations (NGOs and local businesses that install solar systems) with the help of US$750 million in grants and soft loans from multilateral development banks and agencies.21 Ultimately, this public financial support enabled the providers of solar home systems to install them and take monthly payments in arrears, rather than asking (unaffordable) upfront payments.

Bangladeshi village celebrating as they display their first solar panel. Credit: ILO in Asia and the Pacific, Flickr, Licence CC BY-NC-ND 2.0Public investment funds could also be redirected to help a climate transition. Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) oversee an estimated US$7.5 trillion in investments globally and have the potential to invest long term and in climate-friendly, just transition measures that their more commercial counterparts find unattractive.22 SWFs operate according to long-term horizons, a close fit for many of the renewable energy or efficiency projects that will ultimately be needed.23 But SWFs tend to be managed and judged according to market rules and norms that were devised for short-term, for- profit investors, often delegating the investment of a significant proportion of their assets to private fund managers.

In 2015, for example, the Norwegian government’s Pension Fund Global (the world’s largest SWF) announced its intention to divest over US$8 billion invested in coal.24 It has also dropped investments in 60 companies due to deforestation risks, including 33 companies involved in oil palm production. In both cases, divestment was a response to pressure from environmental and consumer protection groups.25

The Pension Fund Global is also taking steps to reduce by US$8 billion its US$36 billion investments in oil and gas, although here the picture is more mixed.26 Part of the divestment push came from activist pressure, which has been supported by technical analyses showing the financial risks of exposure to fossil fuel extraction. Falling returns on oil stocks (due to low prices) and an economic case for diversification made by the Norwegian Central Bank were also key factors. But the scale of the sell-off has been restricted thanks to oil industry lobbying, with the Pension Fund Global maintaining its three largest oil investments (in Shell, BP and Total). Their pressure found a sympathetic ear among some of Norway’s governing conservative politicians – a salutary reminder in a moment of right-wing ascendancy in many countries that divestment is intricately linked to broader political change.

A similar challenge, albeit for different reasons, arises in many of the undemocratic, oil-dependent states that manage most of the world’s largest SWFs. Entrenched elites, who made their fortunes from oil and gas exploitation, are far from the ideal actors to advance divestment from fossil fuels, or develop investment rules that emphasize sustainability and collective well-being. Democratization is likely to be a pre-requisite if most SWFs are to play a constructive role in achieving a just transition. With the most significant SWFs drawing their funds from fossil fuel extraction, their contribution to a just transition should also include significant measures to address the irreparable loss and damage caused by climate change, and finance environmental restoration.

Public pension funds – which manage over US$11 trillion in assets – should also be primed to invest in a climate transition, yet many trail behind their private counterparts in addressing climate change. A 2018 survey by the Asset Owners’ Disclosure Project found that ‘over 60% of the world’s largest public pension funds have little or no strategy on climate change’.27 The reasons behind this are not difficult to find: fund managers have a narrow focus on maximizing economic returns, and do not see climate-friendly investments as particularly profitable. Shifting this perception is more challenging and requires, at its core, a cultural shift in how these funds operate.

Reclaiming the ‘public’ dimension of public pension funds requires, as a bare minimum, that these funds have a core mandate to invest responsibly, with environmental and social as well as economic considerations. While a large proportion of these funds are likely to remain invested in government bonds (which are perceived as relatively secure, reliable investments), longterm investments in public infrastructure that contributes to a climate transition should also be prioritized.28 This can be reinforced by a series of technical changes, including a requirement that addressing ‘climate risk’ and sustainability be part of the fiduciary duty of fund managers, and requiring fund managers to take into account the ‘materiality’ of the risk climate change poses to fossil fuel investments.29

The push for change will ultimately come from public pressure. For example, the California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS) is today seen as one of the most ‘activist’ funds in pursuing socially responsible investment goals but this was not always the case.30 The move to develop a more activist and principled approach to investment was reinforced by efforts to coordinate public investment, such as the formation of a Council of Institutional Investors (which took modest steps to question excessive executive pay awards and improve ‘corporate governance’), and has been driven by initiatives to promote better public investment, such as the non- profit advocacy organization CERES and the Council for Responsible Public Investment.31

CalPERS and CalSTRS (the California State Teachers’ Retirement System) have also been pushed into more climate-responsive investments by legislative changes. Notably, CalPERs and CalSTRS are now required to report publicly on ‘climate-related financial risk’ thanks to Senate Bill 964, passed by the California State Senate in August 2018.32 The impetus for the bill came from environmental groups led by Fossil Free California and Environment California, who were behind the original drafting of the bill as well as a campaign to win support among legislators. This included lobbying political representatives and working for union endorsements from the California Service Employees International Union and the California Teachers’ Association.33

Ultimately, reforming how public investment funds are managed could reposition them as a model for changes that should take place across the private sector, showing that social interest and long-term stability can coincide.

Conclusion: advancing public investment

There is no magic formula for converting public investors into agents of a just transition away from fossil fuels, but the examples identified in this chapter point to several priorities and ways of working. Although the institutional culture of public investors can ignore local development and environmental objectives, it remains susceptible to public pressure. Based on the examples identified in this chapter, priorities should include:

Environmental and social mandates. The core mission of public banks and investment funds should not simply be economic, but should regard environmental and social considerations as equally or more important in investment decisions. This social and environmental mandate should be backed by clearly defined targets and operational rules, such as exclusions of fossil fuel investments and minimum requirements for investment in sectors contributing to a transition (such as renewable energy and effi- ciency).

Embeddedness in broader just-transition plans. The most successful public investment policies are embedded in wider climate change-transition plans. While the implementation leaves considerable room for improvement, Costa Rica’s publicly owned banks are encouraged to promote sustainable investments as just one component of a wider set of carbon reduction and renewables targets.34 In Germany, KfW’s energy efficiency investments form a part of the country’s broader energy transition plan.

Local partnerships. State-led investment can be remote and alienating without a strong connection to local concerns. This is particularly important when developing new infrastructure. Partnerships with local actors, including cooperatives and savings banks, can provide one channel to ensure greater responsiveness to community agendas. Cooperative models of ownership, or other governance structures that enhance worker and community participation, can also help to ensure that infrastructure plans do not override the needs of those affected.

Accountability. State-owned banks and investment funds (including SWFs) need strong rules on transparency and accountability if they are to avoid being captured by vested interests or susceptible to corruption, but pushing for technical changes is not enough. Public investment for the climate is only likely to succeed if it is embedded within broader processes of democratization. Activist pressure can then be brought to bear on lawmakers, as well as finding an echo in how financial regulators frame the environmental risks of fossil fuel investment, or show any willingness to take up social and human rights concerns.

Restorative climate justice. Public investment funds are often sourced from the extraction of fossil fuels. This should be acknowledged in their investment plans, by including ‘restorative’ measures such as providing financial support to help communities address pressing adaptation needs, and the irreparable ‘loss and damage’ caused by climate change.

About the author

Oscar Reyes is an Associate Fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies (ips-dc.org). He is a freelance writer and researcher working on climate finance, the Green Climate Fund, carbon markets and environmental justice. His publications include the (co-authored) Carbon Trading: How it works and why it fails, and the forthcoming Financial System Change, Not Climate Change.

Notas

- Rainforest Action Network et al. (2018) Banking on Climate Change. Available at: http://www.ran.org/wp-content/uploads/rainforestactionnetwork/pages/19540/attachments/origi- nal/1525099181/Banking_on_Climate_Change_2018_vWEB.pdf?1525099181å

- McKibben, B. (2016) ‘Why We need to keep 80 per cent of fossil fuels in the ground’. Available at: https://350.org/why-we-need-to-keep-80-percent-of-fossil-fuels-in-the-ground/

- Reyes, O. (forthcoming) Financial System Change, Not Climate Change. A summary of the report is available at: https://ips-dc.org/report-financial-system-change-not-climate-change/

- Fine, B. and Hall, D. (2012) ‘Terrains of neoliberalism: Constraints and opportunities for alternative models of service delivery’, in D. A. McDonald D. A. and G. Ruiters (eds.), Alternatives to privatization: Public options for essential services in the global South, pp. 45-70, London: Rou- tledge, p. 46

- Schäfer, H. (2017) Green Finance and the German banking system. University of Stuttgart research report 01/2017, p. 15. Available at: https://www.bwi.uni-stuttgart.de/abt3/files/ forschung/BF7_GreenFinance_Banks_Germany_2017.pdf

- Stannard, M. (2016) ‘North Dakota’s Public Bank was Built for the People – Now it’s Financing Police at Standing Rock’, Yes! Magazine, 14 December. Available at: http://www.yesmagazine. org/people-power/north-dakotas-public-bank-was-built-for-the-people-now-its-financing- police-at-standing-rock-20161214

- Peters, A. (2018) ’The Growing Movement to Create City-run Public Banks’, Fast Company, 8 January. Available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/40512552/the-growing-movement-to- create-city-run-public-banks. There have also been setbacks, however, with a ballot measure to support the creation of a Los Angeles public bank falling by a 42:58 margin in November 2018, see Korben, J. (2018) ‘Measure to create L.A. public bank fails’, Los Angeles Times, 7 November. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-public-bank-fail-20181107-story.html

- Stannard, M. (2016), op.cit.

- Marois (2017) Available at: https://theconversation.com/costa-ricas-banco-popular-shows-how-banks-can-be-democratic-green-and-financially-sustainable-82401

- Marois, T. (2016) p. 15; Mukhopadhyay, B.G. (2016) ‘NABARD’s experience in climate finance’. Available at: https://unfccc.int/files/adaptation/application/pdf/asia_6.1c_nabard_experience_ in_climate_finance.pdf

- Morgan, J. and W. Olsen (2011) ‘Aspiration problems for the Indian rural poor: Research on self-help groups and micro-finance’, Capital & Class 35(2): 189-212.

- Bülbül, D., Schmidt, R. and Schüwer, U. (2013) ‘Savings Banks and Cooperative Banks in Europe’, SAFE White Paper 5. Available at: https://safe-frankfurt.de/uploads/media/Schmidt_Buelbuel_Schuewer_Savings_Banks_and_Cooperative_Banks_in_Europe.pdf

- Bülbül et al. (2013), op.cit.

- Marois (2016), op.cit., p. 10.

- Clarke, S. (2010) ‘German Savings Banks and Swiss Cantonal banks: lessons for the UK’, Civitas, p. 10. Available at: http://civitas.org.uk/pdf/SavingsBanks2010.pdf

- Clean Energy Wire (2015) Citizens’ participation in the Energiewende. Available at: https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/citizens-participation-energiewende

- Clean Energy Wire (2015). This structure persists despite recent efforts to incentivize larger scale projects, such as offshore wind, through institutional investment … part of an effort to change the incentives and claw back lost territory for the larger utilities. See Clean Energy Wire (2016)A Reporters’ Guide to the Energiewende, p. 34. Available at: https://www.stiftung-mercator.de/media/bilder/4_Partnergesellschaften/CLEW/CLEW_A_Reporters_Guide_To_The_Energie- wende_2016.pdf

- Martin-Aceña, M. (2013) The savings banks crisis in Spain: when and how?, pp. 88-92. Available at: https://www.wsbi-esbg.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Martin-AcenaWeb.pdf

- “Disruptive” new technologies are also celebrated for their potential to expand financial inclusion. Mobile financial services (especially for payments) are already widely used in sub-Saharan Africa, where a number of companies now offer to install off-grid solar home systems that can be paid for by this means. However, the key factor for expanding off-grid solar is not the payment method, but the fact that public financial institutions have supported schemes that cover upfront installation costs and then allow for monthly payments to be made afterwards.’

- Sanyal, S., Prins, J., Visco, F. and Pinchot, A. (2016) Stimulating Pay-as-You-Go Energy Access in Kenya and Tanzania: The Role of Development Finance. World Resources Institute, p. 18. Available at: http://wriorg.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/Stimulating_Pay-As-You-Go_Energy_Access_in_Kenya_and_Tanzania_The_Role_of_Development_Finance.pdf

- Sanyal et al. (2016), op.cit., p. 21.

- Sovereign Wealth Fund Rankings. Available at: https://www.swfinstitute.org/sovereign-wealth-fund-rankings

- Sharma, R. (2017) Sovereign Wealth Funds Investment in Sustainable Development Sectors. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/high-level-conference-on-ffd-and-2030-agenda/ wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2017/11/Background-Paper_Sovereign-Wealth-Funds.pdf

- Carrington, D. (2015) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jun/05/norways-pension-fund-to-divest-8bn-from-coal-a-new-analysis-shows

- Alfesn, M. (2018) ‘The Day the Norwegians Rejected Palm Oil and Deforestation’, Rainforest Foundation Norway. Available at: https://www.regnskog.no/en/long-reads-about-life-in-the- rainforest/the-day-the-norwegians-rejected-palm-oil-and-deforestation-1

- Vaughan, A. (2019) ‘Norway is Starting the World’s Biggest Divestment in Oil and Gas’, New Scientist, 8 March. Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2196024-norway-is- starting-the-worlds-biggest-divestment-in-oil-and-gas/

- Asset Owners Disclosure Project (2018) ‘60% of the world’s largest public pension funds in breach of duties on climate change, new data reveals’. Available at: https://aodproject.net/ranking-public-pension-funds-2018/

- Lipschutz, R. D. and Romano, S. T. (2012) The Cupboard is Full: Public Finance for Public Services in the Global South, p.24. Available at: https://www.municipalservicesproject.org/sites/municipalservicesproject.org/files/publications/Lipschutz-Romano_The_Cupboard_is_Full_May2012_ FINAL.pdf

- EU High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (2018), p.23; Task Force on Financial Disclosures.

- p.40-41 https://www.municipalservicesproject.org/sites/municipalservicesproject.org/files/ publications/Lipschutz-Romano_The_Cupboard_is_Full_May2012_FINAL.pdf

- CalPERS was a founder member of the Council of Institutional Investors and the International Corporate Governance Network, which have emphasized the need for more transparent ‘corporate governance’ (especially around executive pay awards), and advocated for investors to take a more active role in voting for or against Board resolutions proposed by companies. These initiatives that laid the groundwork for forms of ‘shareholder activism’ that have curtailed some of the worst corporate excesses, and led to the adoption of climate resolutions (e.g. requiring management to make climate risk assessments before investing), although the power of this tool is limited in terms of instigating more transformative changes.

- Thompson, J. (2018) ‘California turns up the heat on climate change disclosures’, Financial Times, 29 September. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/a4c8fffa-869a-3e76-8e05-e8acc572d293

- Cox, J. (2018) ‘SB 964 clears its first hurdle’, 12 April. Available at: https://fossilfreeca.org/2018/04/12/sb-964-clears-its-first-hurdle/ ; http://fossilfreeca.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/SB-964_talking-points.pdf

- It should be noted that there is some controversy over the actual level of Costa Rica’s ambition, since its ‘carbon neutral’ goal relies on claims about tree planting and land use changes that are inherently difficult to measure. See, for example: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/costa-rica/