This essay is part of the book Public Finance for the Future We Want, you can find the entire collection of essays here.

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, the Euro area has experienced a sovereign debt crisis, a double-dip recession and severe risk of deflation. This last decade was marked by quasi-stagnation of economic growth, stubbornly high unemployment in several countries and rising climate and environmental concerns, all of which would call for investment in crucial sectors.

As the true backbone of our society, investment in infrastructure can no longer be overlooked without harmful consequences to the well-being of citizens, not to mention any transition to a sustainable and low-carbon society. Meanwhile, public spending is largely constrained, notably due to the implementation of a new set of EU fiscal rules called the Fiscal Compact. To close the investment gap, the EU has taken on the role of mobilizer of private capital. Yet, EU efforts have failed to stimulate the economy and fill the investment gap: private investors are not particularly interested in long-term, potentially risky and comparatively not-so-profitable investments.

Clearly the scale of the twenty-first century’s ‘Grand Challenges’ such as climate change and nature’s depletion call for patient and strategic capital. In this regard, we argue that the potential of state investment banks has been largely overlooked, and too often restricted to de-risking private investment.

More precisely, we will discuss the proposition to establish a Eurosystem of State Investment Banks, whose activities would be supported through the reinvestment of money created by the European System of Central Banks in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Designed with an unambiguous mandate to provide strategic long-term investments and with explicit sup- port from the European Central Bank (ECB), such an enhanced cooperation between already existing European public investment banks would help us transition towards a truly sustainable economy.

The crumbling backbone, the climate and the need for public investment

From roads to water, electricity, schools and other public facilities, govern- ments are increasingly urged to maintain the existing, failing infrastructure, and make stopgap improvements. The need for infrastructure investments has been continually quoted as one of the great challenges of the com- ing decades. Without urgent infrastructure investments the well-being of citizens and the proper functioning of the economy will suffer. Indeed, a large body of literature has emphasized their significant positive effects on potential gross domestic product (GDP), and above all their potential for making societies more sustainable and inclusive.

Box I

Climate change and the cost of the transition According to the latest report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, we have just over a decade to limit climate change catastrophe. Public investments will be needed for retrofitting to improve the energy efficiency of existing buildings and infrastructure. There will also be a need for additional investment in energy infrastructure, green infrastructure and infrastructure to deal with changing climatic conditions and extreme weather events, such as improved sea defences and flood protection. The European Court of Auditors estimates that €1.115 billion needs to be allocated each year in Europe between 2021 and 2030 to fight climate change and its effects.

Several studies show that there is a growing infrastructure investment gap worldwide, estimated at US$18 trillion by 2040. The European Union needs investments of €688 billion per year between 2015 and 2030 in energy, transport, water and sanitation, and telecoms.1 This represents 4.7 per cent of the EU’s GDP.

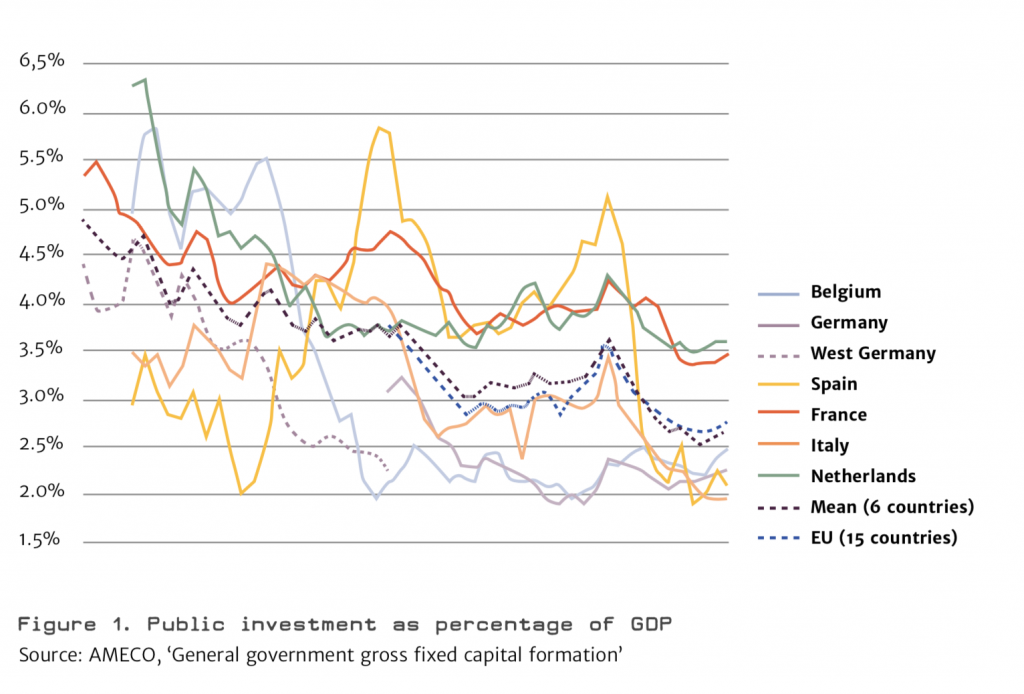

While public investment as a share of GDP was levelling out at 2.7 per cent in 2017 in Western Europe (EU-15), reaching a 50-year low (see Figure 1), investment in infrastructure in the EU today is even lower at a worrying 1.8 per cent of GDP according to the European Investment Bank (EIB).2 This is 20 per cent below pre-crisis levels and a far cry from what is needed. And there is little sign of improvement.

Nowadays, there is limited flexibility in public investment levels in EU countries, largely as a consequence of the so-called Fiscal Compact. This 2012 intergovernmental treaty aimed at ensuring that governments reduce their spending to comply with the original 1992 Maastricht Treaty criteria – that is, their financing deficit should not exceed 3 per cent of GDP and the ratio of public debt to GDP should not exceed 60 per cent. This has resulted in a sustained drop in public investment despite the crucial need to lift such fiscal constraint.3

Evidence shows that fiscal policy should permit counter-cyclical public investment. In other words, public investment should increase when the economy is slowing down, and unemployment is high. As a matter of fact, the fiscal multiplier being higher than the cost of debt, public investment funded by debt would be beneficial for the level of public debt: if an increase in GDP produced by investments is greater than the increase in debt, the ratio of debt to GDP decreases. In other words, public investment could pay for itself but is forbidden nonetheless.

When the public interest is at stake, but states are constrained from providing investment, could private finance be the answer? We think not.

Private finance and the investment gap

Large institutional investors such as pension funds or insurance companies have been presented by international organizations – led by the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development – as well-suited to invest in infrastructure and low-carbon projects. But investors have been clear about what this will take: investments that can offer competitive returns.

Consequently, a large part of the public policy narrative is that public guarantees are needed to mobilize private funding by reducing the risk of private investment in infrastructure.4 This narrative notably incentivizes EU governments to resort to public–private partnerships (PPPs), as these circumvent the Fiscal Compact constraints. As an EIB paper puts it ‘since fiscal accounting rules keep most PPPs off the balance sheet, governments have used them to anticipate spending and to sidestep the normal budgetary process’.5 But in fact PPPs do not eliminate fiscal constraint over the long term and are not less costly. Instead, they are a form of regulatory arbitrage that shifts the cost of projects to future generations.7 On top of that, the level of PPPs in Europe is historically low and is nowhere near meeting infrastructure needs. Since the 1990s, a total of 1,749 PPPs worth a total of €336 billion have reached financial close in the EU.8 There is a similarly low average in infrastructure investment by large institutional investors worldwide, amounting to only 1.1 per cent of their total assets under management.9

Regarding climate mitigation and adaptation investment, there is also a long way to go: while the financial sector comprised more than US$294 trillion in assets in 2014, ‘sustainable-themed investment’ represented US$1 trillion in 2018,10 ‘climate finance’ amounted to US$455 billion11 worldwide and the famous global ‘green bonds’ market was worth just US$155.5 billion in 2017.12

Although there is clearly an abundance of liquidity, the lack of private financing of infrastructure and climate mitigation and adaptation investment suggests that they are just not profitable enough in the short term — and the short term is their horizon.13

However, profit should not be the metric for everything. ‘Grand challenges’ such as the fight against climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy call for patient, long-term, committed finance. And this will never be the specialty of global private finance — at least in the absence of specific regulatory incentive (e.g. credit guidance) — but it is the bread and butter of another actor: state investment banks.

State investment banks: going beyond the socialization of risk and privatization of profit

By nature, state investment banks (SIBs) such as the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), the Italian Cassa depositi e prestiti (CDP) or the French Caisse des dépôts et consignations (CDC) are different from private commercial banks or institutional investors: they are created with a public interest mandate to provide medium- and long-term capital for productive (and sometimes green) investment. While governance structures and accountability mechanisms are key to avoid mission drift and political capture, their explicit public mandate and guarantee can enable SIBs to see beyond the pressure to deliver short-term returns. Consequently, these often-underestimated institutions can play an important counter-cyclical role in the aftermath of crises, as they did between 2007 and 2009 by increasing their loan portfolio from 35 per cent on average to more than 100 per cent.14

In fact, under some conditions the business activities of SIBs neither affect the general government deficit or surplus nor its gross debt.15 Therefore, SIBs are currently one of the ways for European states to release the constraints of EU fiscal rules in order to maintain a form of public investment and foster in some cases a discreet industrial policy through loans targeted towards specific sectors.16

Nevertheless, their potential does not match the investment gap because their role is too often limited to fixing ‘market failures’ and de-risking private investment. As a flagship example, the post-crisis Investment Plan for Europe is essentially about mobilizing private funding. In this context, SIBs, but also the multilateral EIB, are required to provide public guarantees and to purchase the riskiest tranches of investment in infrastructure to incentivize institutional investors to get on board.17

Instead, we should put our energy into allowing public financial institutions to do more of what they are good at: directly financing infrastructure and long-term investment in public goods and commons.

Eurosystem of investment banks

In 2014, the economist Natacha Valla, Deputy Director General for Monetary Policy at the ECB, proposed the establishment of a Eurosystem of Investment Banks (ESIB) ‘around a pan-European financial capacity that would coordinate the actions of the [state] investment banks of Euro area member states and add to their funding capacity’.18 Building on the existence of a network of prominent SIBs across Europe and the EIB, the ESIB would institutionalize their occasional successful cooperation — notably the so-called ‘investment platforms’ — in European Law with the binding mandate of promoting sustainable and inclusive growth, and employment on the continent. Considering the risk of climate change and environmental collapse, this mandate should involve the transition to a sustainable and low-carbon economy.

The proposal is to finance investment at an economically relevant scale of €1 trillion per year, but it was also suggested that the European Fund could issue debt to finance itself on the market. While the actual abundance of liquidity could advocate in favour of such an option, it is neither the only way to go nor the best as it incentivizes SIBs to select profitable and not- too-risky investment in order to keep their generally good rating — the kind of investment that could easily attract private money.

Of the many ways SIBs can finance their operations — including taking savings and deposits from the public, borrowing from other financial in- stitutions, receiving budget allocations from the national Treasury19 — we think there is room for reinforcing one particular channel of funding: the central banks.

Money creation for the people?

We tend to forget that how we create money and the quantity in circula- tion are key in our economy; the latter can potentially restrict the value of transactions if too low and lead to inflation if too high. The role attributed to central banks is precisely to ensure a proper level of money in circulation to realize the economy’s full capacity and reach full employment.

But who is creating and allocating money is also an important issue to address. With commercial bank lending now the main source of money issuance, it is important to know under what conditions and to whom banks are lending. Compared to private banks that are designed to provide funding for profitable activities and not-too-risky clients, public banks can be democratically mandated to pursue other objectives such as social inclusion, full employment and a transition to a sustainable and low-carbon economy.

The limited and not-so-effective central banks toolbox

In response to the 2008 crisis, major central banks promptly reduced interest rates to near-zero in an attempt to make it cheaper for private banks to lend money to businesses and individuals; in a less conventional move they also launched ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) programs that allowed them to create money and purchase various financial assets, including government and corporate bonds. The money injected through QE was supposed to trickle down to the real economy by pushing financial markets and banks to lend more. In the Eurozone, QE was also meant to make it easier for governments to sustain their deficits, by reducing the interest rate and the risk on government bonds.

Launched in 2015, QE as implemented by the ECB has resulted in the creation of more than €2.6 trillion. Following the principle of so- called ‘market neutrality’, the ECB bought bonds on the market without differentiating between ‘brown’ and ‘green’, or between socially useful and harmful investments. While this policy massively directed towards Euro- area sovereign bonds has successfully stopped speculation on the poorest countries in the region, the ECB has so far failed to achieve its primary mandate of maintaining inflation close to 2 per cent despite this massive injection of liquidity: inflation is still far below that level.

This comes as no surprise. Firstly, cheaper borrowing does not necessarily lead to increased demand from households and companies, especially when they already have a hard time repaying their existing debts and when the economy is depressed. Secondly, given monetary policies are intermediated by a dysfunctional financial sector, money does not automatically reach the real economy: financial development since 1990 has mostly grown thanks to credit for real estate and other asset markets,20 not business lending. For example, by the end of 2017 ‘almost 40 percent of ECB-created liquidity was kept idle on credit institutions’ deposit accounts at the ECB itself’21 rather than used to provide new loans to the real economy. In this context one wonders how QE could stimulate the economy.

Many economists are currently debating whether central banks have exhausted all their options, implying that they could not cope with another financial crisis. This sheds light on the limitations of the current monetary policy toolbox and reopens the debate on other instruments, especially coordination between fiscal and monetary policies.

The use of a central banks’ money-creating powers to help finance public investment is not a new idea. A number of economists advocated for similar policies as a response to the Great Depression in the 1930s.22 Before the era of modern banking, several governments ‘used simple accounting techniques … or printed paper money to fund their activities and ensured their widespread adoption through taxation’.23 There are also many examples of fiscal–monetary coordination through history, in particular during the 1930s to 1970s period.24

Despite decades of fruitful coordination between central banks and minis- tries of finance, such practices have become taboo with the establishment of a New Macroeconomic Consensus (NMC) in the 1990s. Inflation targeting has since become the primary focus of monetary policy, taking over other macroeconomic policy objectives such as full employment or sustainable growth. The NMC’s two other key elements are: first, that central banks should be strictly independent from government; second, that they solely use indirect methods of monetary policy (e.g. interest rate adjustment) versus direct methods (e.g. monetary financing of public investment or some forms of credit guidance). In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty institutionalized this consensus in Europe by preventing any government from monetarily financing public investments.

However, this consensus was called into question after the 2008 crisis, reopening the discussion on using central bank money creation to support public investments. Following the resurrection of this idea in 2003 by the former chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, it has been endorsed by notable economists, including the former Financial Services Authority chairman Adair Turner, the Citigroup’s chief economist William Buiter, the Nobel Prize-winning Paul Krugman and others.25

A partial monetary financing of public investment through such coordi- nation could help close some worrying investment gaps — such as for the transition to a sustainable and low-carbon economy — and influence pro- duction and employment, directing capital where it is most needed, without heightening the public sector’s debt. Nevertheless, for most policy-makers, ‘printing money’ to finance public spending remains a mortal sin26, as it triggers fear of hyperinflation.

Monetary financing to prevent climate breakdown

Creating money is what the banking sector does every day. The question is whether this new money created corresponds to real productive activities that fulfil society’s needs, or if it is going to inflate the price of existing assets, creating a risk of a bubble and artificially expanding the wealth of the few. Redirecting money creation towards real activity, especially for the transition, would certainly not bring any uncontrollable inflation.

To make it politically viable in Europe, the main characteristics of our pro- posal would be:

- Conditionality – To overcome the mostly irrational fear of triggering hyperinflation, monetary financing would be made conditional, so that bond purchases would be automatically stopped in case of a too-high surge in inflation – as has been proposed by some economists.27

- Reallocation – The funds would be made available to every SIB accord- ing to country capital key,28 for the purpose of financing long-term public and sustainable investment projects.

- Guarantee – The creation of a Eurosystem of SIBs combined with a pre- announced and substantial volume of purchases by the ECB of newly created ESIB bonds will act as a strong guarantee for this new mechanism. This will allow SIBs to fund riskier and less profitable — but necessary — projects with public good characteristics, and to benefit from extremely low interest rates in case the ECB stops buying ESIB bonds beyond a certain threshold.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that this could eventually be done without new money creation. Despite the supposed end of quantitative easing in December 2018, every time a bond will arrive at maturity, the ECB will reinvest the correspondent amount of money into new bonds29 — the same sort of reinvestment will happen for years to come. The ECB could therefore decide to buy a greater amount of ESIB bonds with this reinvestment. As the ESIB would mainly emit green bonds directed towards the transition (e.g. sustainable infrastructure), reinvesting QE that way would allow the ECB to finally channel it towards the real economy and fulfil its duty as an institution legally bound by the Paris Agreement on climate change.

In any case, this would help to quickly close the investment gap in the areas of climate mitigation and sustainable infrastructure, while reducing general levels of unemployment.

Conclusion: there is no inflation on a dead planet

Enhanced cooperation between public investment banks and central banks could boost crucial public investment, but any ambitious proposal needs civil society advocates and public engagement.

As the ‘Pacte Finance Climat’ is being discussed in France largely thanks to broad public engagement, civil society actors like Positive Money Europe are already putting some pressure on the ECB to go green. In the same vein, citizens and civil society need to demand that their national parliaments question the kinds of (dirty) bonds that their central banks buy, and that they redirect QE into green investments.

Policy-makers and central bank governors should be reminded that there is no inflation on a dead planet. The irrational fear of inflation should not prevent our generation from finding solutions to the biggest threat to the survival of mankind: the risk of a climate breakdown.

About the author

Ludovic Suttor-Sorel is Research and Campaign offi- cer at Finance Watch, a European NGO that act as a counter-balance to the finance lobby in Brussels. Before joining Finance Watch, Ludovic worked for Positive Money Europe on the role of central banks in scaling up green finance. As a researcher in Applied Economics at the ULB, he worked on environmental policy and public incentives. His first work on financial and banking regulation at the political level was undertaken for the office of a Belgian Senator.

Notes

1 EIB (2016) Investment and Investment Finance in Europe: Financing Productivity Growth, European Investment Bank Report. p. 63.

2 EIB (2018) Investment Report 2017/2018: from recovery to sustainable growth, European Investment Bank Report.

3 Member states may only apply the so-called ‘investment clause’ under very strict conditions ’it only applies to countries with either negative GDP growth in terms of volume, or GDP far below potential, which results in a negative output gap of more than 1.5% of GDP. Furthermore, na- tional investment expenditure is only eligible if projects are co-financed by the EU … The devia- tion should not lead to an exceedance of the 3% deficit threshold … The deviation should also be offset within … four years from the entry into force of the investment clause… These conditions can be qualified as strict, since only a limited number of countries meet them … only Finland was still eligible in 2016.’ Crevits, P., Melyn, W., Modart, C., Van Cauter, K. and Van Meens, L. (2017) Public investments – analysis & recommendations. Brussels: Banque Nationale de Belgique, p. 21.

4 State Investment Banks (KfW, CDP, CDC, ICO, etc.), but also the multilateral EIB, recently gained a stronger role in the Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union and in the Investment Plan for Europe. As part of this broader EU plan to foster market-based finance, the SIBs are asked to provide public guarantees and purchase of mezzanine and senior tranches. See Mertens, T. (2018) Market-based bus state-led: The role of public development banks in shaping mar- ket-based finance in the EU. Competition and Change, January.

5 Engel, E. M. R. A., Fischer, R. D. and Galetovic, A. (2010) The economics of infrastructure finance: Public-private partnerships versus public provision, EIB Papers, Vol. 15, Iss. 1, pp. 40-69. Luxem- bourg: European Investment Bank.

6 [A] 2015 review by the UK’s National Audit Office (NAO) found “that the effective interest rate of all private finance deals (7%-8%) is double that of all government borrowing (3%-4%)”. In other words, the costs of financing of PPP-operated services or infrastructure facilities were twice as high for the UK public purse than if the government had borrowed from private banks or issued bonds directly.’ In ROMERO, M. J. (2018) ‘The fiscal costs of PPPs in the spotlight’, UNCTAD, Investment Policy Hub, 13 March.

7 Hache, F. (2014) ‘A missed opportunity to revive “boring” finance? A position paper on the long- term financing initiative, good securitization and securities financing’. December. Brussels: Finance Watch, p. 22.

8 European Court of Auditors (2018) ‘Public Private Partnerships in the EU: Widespread shortcom- ings and limited benefits’. Special report. p. 9.

9 OECD (2016) Survey of Large Pension Funds and Public Pension Reserve Funds. p. 41.

10 Which encompass investment that address specific sustainability issues such as climate change,

food, water, renewable energy, clean technology and agriculture. Source: GSIA (2019) 2018 Global

Sustainable Investment Review, April.

11 Climate Policy Initiative (2017) Global Landscape of Climate Finance.

12 CBI (2017) Green Bond Highlights.

13 While long-term investors like pension funds have liabilities beyond 20-30 years, it does not

mean that it is the time frame of their investment. As the performance of asset managers — which manage the assets on behalf of a majority of institutional investors — are generally evaluated on a quarterly basis, this puts pressure on them to deliver short-term returns. As an illustration, ‘long-only equity fund managers’ turn over their portfolios on average 1.7 years and 81 per cent of them do so within three years. See Bernhardt, A., Dell, R., Ambachtsheer, J. and Pollice, R. (2017) The long and winding road: how long-only equity managers turn over their portfolios every 1.7 years. MERCER, Tragedy of the Horizon program.

14 De Luna-Martinez, J. and Vicente, C.L. (2012) Global Survey of Development Banks, Policy Research Working Paper 5969. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

15 Investment made by the SIBs are not allocated to the government sector according to the European System of National and Regional Accounts framework (ESA 2010), at least when they act as a financial intermediary and are sufficiently autonomous in performing its duties. See Romano, C. and Theodore, S. (2018) Issuer Rating Report of [KfW], Scope Ratings, Berlin, 30 August.

16 For example, ‘Germany, continues to use state-owned banks to allocate credit to priority sectors in order to conduct industrial policy … [through] its largest national development bank, the [KfW]’. See Naqvi, N., Henow, A. and Chang, H.-J. (2018) ‘Kicking away the financial ladder? German development banking under economic globalization’, Review of International Political Economy.

17 Mertens, T. (2018) ‘Market-based bus state-led: The role of public development banks in shap- ing market-based finance in the EU’, Competition & Change 22(2): 184–204.

18 Valla, N. (2015) Investment in Europe needs a new architecture: the Eurosystem of National Promotional Banks, p. 112-129 cited in Garonna, P. and Edoardo, R. (eds.) (2015) ‘Investing in Long-Term Europe. Re-launching fixed, network and social infrastructure’ Luiss University Press.

19 McFarlan, L. and Mazzucato, M. (2018) State investment banks and patient finance: An interna- tional comparison, Working Paper 2018-01). UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, p. 5.

20 The share of mortgage loans in banks’ total lending portfolios has roughly doubled over the course of the past century – from roughly 30 per cent in 1900 to roughly 60 per cent today. See Jordà, O., Schularick, M. and Taylor, A.M. (2014) The Great Mortgaging: Housing Finance, Crises, and Business Cycles, NBER Working Paper No. 20501, September; BezemeR, D., Grydaki, M. and Zhang, L. ‘Is financial development bad for growth?’ Research institute SOM Research reports. Groningen: University of Groningen.

21 Botta, A., Tippet, B. and Onaran, O. (2018) Core-periphery divergence and secular stagnation in the Eurozone, FEPS, June.

22 ‘Paul Douglas and Aaron Director (1931), Lauchlin Currie, Harry Dextor White and Paul Ellsworth (1932), John Maynard Keynes (1933), Jacob Viner (1933) and Henry Simons (1936). Later, the idea was further developed by Abba Lerner (1943) and Federal Reserve Chairman Mariner Eccles (1942). It was most notably endorsed by Milton Friedman in 1948.’ See Van Lerven, F. (2015) Recovery in the Eurozone, Positive Money.

23 Ryan-Collins, J. (2015) Is Monetary Financing Inflationary? A Case Study of the Canadian Econo- my, 1935–75, Working paper no. 848. Levy Economic Institute.

24 Ryan-Collins, J., Van Lerven, F. (2018) Bringing the helicopter to ground: A historical review of fiscal-monetary coordination to support economic growth in the 20th century, Working Paper 2018-08. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose.

25 ‘Richard Werner (2012); Richard Wood (2012); Martin Wolf (2013); Paul McCulley and Zoltan Pozsar (2013); Steve Keen (2013); Yannis Varoufakis (2014); Ricardo Caballero (2014); David Graeber (2014); John Muellbauer (2014); Mark Blythe, Eric Lonergan and Simon Wren Lewis (2015)’ See Van Lerven, op.cit.

26 In a speech, the President of the Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann, cited the story of Goethe’s Faust, in which an agent of the devil tempts the Emperor to distribute paper money, increasing spending power, writing off state debts, and fueling a dynamic that ‘degenerates into inflation, destroying the monetary system’.

27 Watt, A. (2015) Quantitative easing with bite: a proposal for conditional overt monetary financing of public investment. Department Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) of the Hans-Böckler Foundation.

28 Each national central bank accounts for a fixed percentage of the ECB capital – the capital key. The key is calculated according to the size of a member state in relation to the European Union as a whole, size being measured by population and GDP in equal parts.

29 ‘The Governing Council intends to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time after the end of the net asset purchas- es, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favorable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation.’ See ECB (n.d.) Asset purchase programme. https:// www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omt/html/index.en.html