The Financialised Firm

How finance fuels and transforms today’s corporation

Myriam Vander Stichele

STATE OF POWER 2020

January 18, 2020

An increasing number of businesses have become emblems of corporate crimes and violations—Bayer for toxic agrochemicals, Exxon for obstructionism on climate issues, Uber for its drivers’ working conditions. A wide range of corporations, however, rarely receive public attention let alone become the target of public anger. Without them, however, corporations that are known for their abusive practices could not operate in the way they do. They include the law firms that plead for their impunity, the marketing firms that promote unhealthy products, the tech companies that help covertly target clients, the lobby firms that corrupt democratic spaces and manipulate public opinion, the auditors and tax consultants that advise on tax dodging.

These corporate servants take no responsibility for their clients’ socially and environmentally abusive practices—and there are no sanctions for doing so, thus creating a chain of impunity.

Yet where would Bayer be without Bank of America/Merrill Lynch and Credit Suisse, which helped finance its take-over of Monsanto? Where would Uber be with its practice of bending national laws without the support of legal firms like Covington & Burling? Like the corporations for whom they provide services, many of these are also now globalised and transnational conglomerates, extracting huge profits.

This essay will focus on one sector that has done more than any other to drive abusive corporate behaviour and impunity: the financial industry. Its various players have not just provided services, they have also made it easier for corporations to ignore social and environmental responsibility and reshaped the corporation—resulting in the financialisation of the whole economy.

Loans that allow abuses

Lending is the most basic service the financial industry provides to corporations as a whole or for particular corporate activities. Banks that lend to large corporations tend to specialise in particular sectors in order to optimise their services and risk assessments and so offer attractive interest rates to their clients.

A system of revolving credit allows corporations to borrow over a period of time without further bank assessments. Big corporations can obtain hundreds of millions or billions of dollars through a syndicated loan by an ad hoc consortium of large banks (a syndicate), each lending a slice of the loan after one or more ‘lead arrangers’ have made an assessment of the corporation or project.

In the case of the Dakota Access pipeline, for example, Citibank led a consortium of 17 international banks to provide a $ 2.5 billion syndicated loan. This is one of many examples of how banks’ risk assessments do not properly take climate, environmental and human rights into account.

The research and campaign group BankTrack has investigated and exposed the banks that lend to large polluting and carbon-intensive corporations or projects. Since the 2015 Paris climate accord, for example, global banks’ lending to the fossil-fuel industry has increased every year, pumping $1.9 trillion of new money into the development of fossil fuels, even to the dirtiest kind of energy extraction.

Similarly, years of campaigning by Friends of the Earth (FoE) in the Netherlands to stop decade-long lending to destructive palm-oil companies pushed the Dutch banks to develop a lending policy on palm oil, but did not stop them lending.

The banks have responded by issuing policies and guidelines, but without making any significant changes in practice.

Banks have even sold off risky loans by repackaging them and transferring them to investors, allowing the loan to continue with little risk to the bank but more risk for the financial system (‘securitisation’—a cause of the 2008 financial crisis).

Banks started to globalise in order to provide services to their corporate clients that expanded abroad. Now they advise on how to find business partners in third countries, or how to export or import. They provide trade credit to importers and guarantees of payment to the related exporters, without which international trade would come to a halt—as became clear when banks stopped financing trade when the financial crisis blew up in 2008.

Banks develop a complex mix of financial instruments to help finance large trade deals, including using the traded produce as collateral.

Not just serving but increasing corporate power

Large banks are not only serving their corporate clients, but also seek opportunities for one corporation to merge with and acquire with another—because the bigger the company, the more loans and financial services it will require. It is no secret that banks favour loans to supermarkets rather than to a corner shop because the business opportunities are far greater.

Investment bankers are therefore crucial players in building giant corporations and corporate concentration in most sectors of the economy. They develop financial merger and acquisition (M&A) plans involving loans and shares, benefits for the top management and cuts in costs— and, importantly, huge fees for the investment bank.

The planned cost-cutting often results in staff redundancies in overlapping activities and proposals on how to use, or abuse, greater purchasing power to push down suppliers’ prices—setting a downward income spiral through the supply chain. Investment bankers, however, still cash in high bonuses and are proud of their M&A deals, even when these subsequently fail.

Big deals for ever bigger pharma

While many people around the world cannot afford costly drugs and have no access to health insurance, large pharmaceutical corporations have no issues with finance, including for expensive M&A deals.

For instance, Celgene obtained US$ 74 billion to acquire Bristol-Myers Squibb. The five investment banks providing advice (including Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan Chase, and Citigroup) received US$304 million in fees. The banks that provided a US$ 33.5 billion loan received US$ 547 million in interest payments.

These costs will be repaid by increasing the price of drugs, regardless of the impact on people’s health.

Rising drug prices goes against the global commitment of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3, target 8 to achieve ‘access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all’. Yet the banks that undermine this are never deemed responsible or liable.

The financing of huge M&A deals leads to a vicious circle of bigger banks and bigger corporations. The public outcry against ‘too-big-to-fail’ banks that needed to be bailed out with taxpayers’ money has not resulted in splitting the banks, since a proposed EU law was aborted. This was not just a result of bank lobbying. Big multinationals also lobbied against restructuring the major banks, arguing they needed them to finance their complex deals.

Fewer corporate giants mean more profits for rich investors who in turn demand ever greater profits.

Fewer corporate giants mean more profits for rich investors who in turn demand ever greater profits. Corporate concentration in a context of weakened competition (anti-trust) laws—thanks to lobbying—lead to less bargaining power for workers and suppliers, and higher prices for consumers.

Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warns that ‘with higher market power, the share of firms’ revenue going to workers decreases, while the share of revenue going to profits increases’.

Creating the shareholder bonanza and reshaping corporate investment

Beyond loans, perhaps the most critical financing role the banks play is in creating parallel financing structures.

Investment banks provide various services that allow large corporations to be financed by issuing shares or corporate bonds, called underwriting.

First, they advise the corporation on how to become more profitable and attractive to shareholders and bond holders, for example by advising tax-dodging strategies channeled through the bank’s offshore subsidiaries or branches.

The banks then analyse the prospects and risks to the corporations’ profitability—or in the case of new technology companies, how interested investors might be in buying and trading the shares, even if there will be no profits for years, as was the case for Amazon and Uber. They get credit-rating agencies (see below) to give investment grades.

The banks collate their analysis in a prospectus, with no legal obligation to assess the corporation’s social or environmental impacts unless these might threaten its profitability.

For instance, Uber’s prospectus mentioned the risks that its independent drivers could be legally entitled to be paid as employees, but made no mention of how it might increase pollution in cities by replacing public transport.

Second, the banks ensure the listing of the shares and bonds on a stock exchange or off exchange.

Third, once the banks have valued the new shares, they buy the shares and take a risk of non-selling while organising ‘road shows’ to promote the shares among investors. This underwriting of risks is usually shared among a number of large banks.

In the initial share issuance and underwriting of Uber, for example, 29 banks were involved, 11 of which were also involved in the earlier issuance of shares by Lyft, Uber’s competitor. Some of the top banks were Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, others included Barclays Capital, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Citigroup Global Markets Corporations and Deutsche Bank Securities.

Share issuance allows corporations to diversify funding from loans or bonds that need to be repaid. Underwriting banks receive huge fees for issuance of new shares, and do not have to set aside costly capital reserves for loans. The underwriters of the Uber share issuance received fees of $106.2 million.

Campaigners are beginning to place the spotlight on banks involved in share issuance. News in 2019 that Saudi Arabian oil company, Saudi Aramco, was moving ahead with offering shares led to a coalition of environmental groups warning investors of the dangers of facilitating capital for the world’s largest corporate emitter of CO2 as well as supporting a regime with an appalling human rights record. As Western investors became lukewarm, investment banks decided to focus on selling the shares to investors in the Gulf region, themselves oil producers, rather than withdrawing from the issuance altogether. Saudi Aramco was able to cash in a record $29.4 billion by mid-January 2020 claiming it will diversify away from oil.

Investment banks and others serve shareholding investors by analysing the profitability of listed corporations. These financial analysists are very instrumental in putting high and constant pressure on company managers to increase profitability, amongst others by comparing them with companies in the same sector. Investment banks also facilitate share trading on the stock market but there might be a conflict of interest if they are involved in underwriting those shares. They help avoiding the dropping of share prices in case of large sell-offs by dividing up the sales of large chunks of shares on their non-public trading platforms, known as ‘dark pools’.

It is estimated that trading on dark pools accounted for approximately 40% of all US stock trades in early 2017 compared with an estimated 16% in 2010. High-value shares offer corporations continued access to financing and opportunities to undertake M&A deals, bolstered by the growing practice of corporations of buying back their shares.

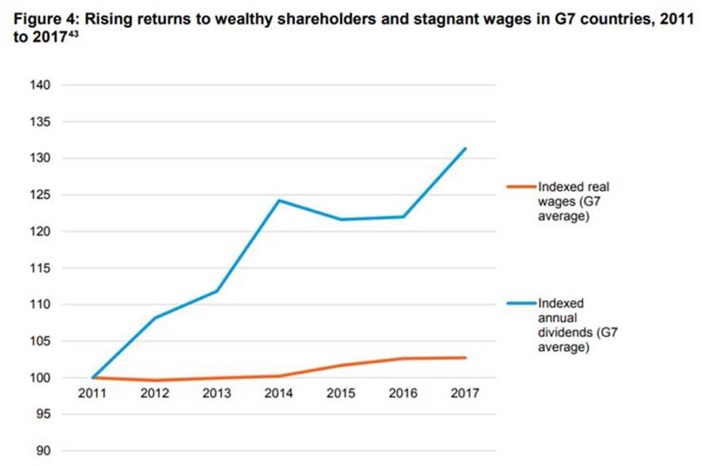

In fact, top managers’ pay with shares options is a further incentive to prioritise high share value and buying back shares over innovative investment or employment. The relentless pressure for high returns to shareholders—the institutional investors, the extremely wealthy and the top managers—has been a big part of the increasing wage gap.

In the US, almost $7 trillion went to shareholders as dividend payments and shareholder buy-backs while workers’ income hardly rose, fuelling inequality and also depressing workers’ purchasing power.

This primacy of shareholder value had a significant impact on corporate strategy. At the start of the 1980s, 50% of profits were reinvested in the corporation, but by 2018 this had fallen to 7%.

Concentrating power in the financial sector

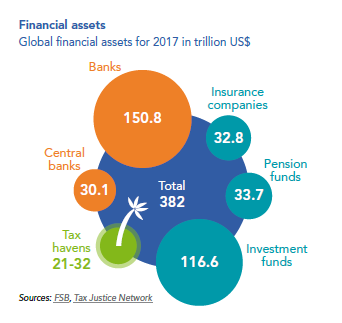

The growth of shareholding and corporate bonds issued by ever larger corporations has been supported by financial concentration in the hands of the trillion-dollar investment fund industry.

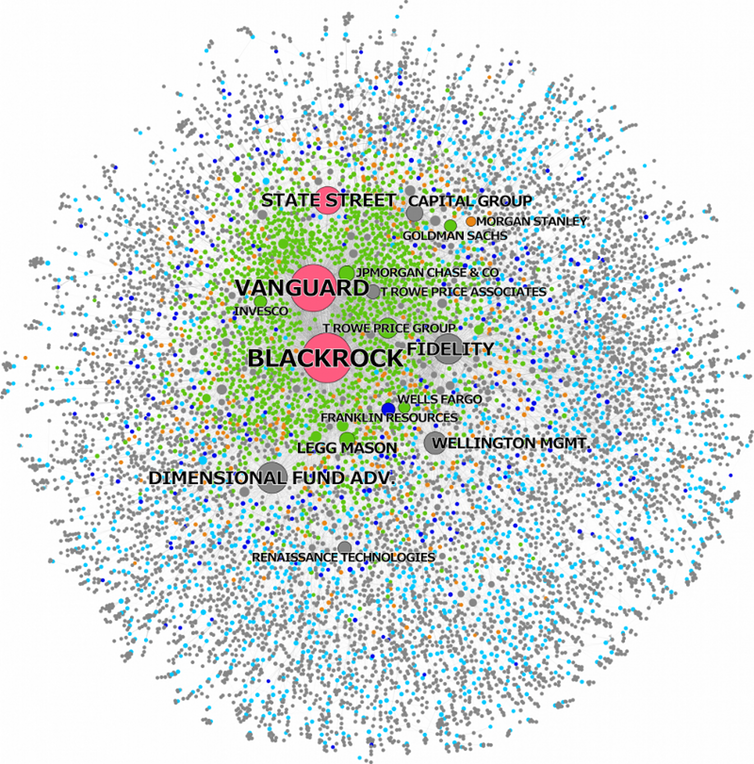

New financial giants have emerged, dominated by BlackRock (the largest global investment management company with US$ 7 trillion in assets under management), Pimco (specialised in bond investment management with US$ 1.9 trillion under management), Vanguard (the second largest global investment fund manager with $5.6 trillion in assets under management) and Amundi (a top European asset manager with € 1.56 trillion assets under management). They now hold shares and/or bonds in almost every company in the world.

A study of US companies showed that the three top investment fund managers —BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street—are the largest single shareholder in almost 90% of the top 500 firms worldwide listed in the S&P index, including Apple, Coca-Cola, ExxonMobil, General Electric and Microsoft.

Since most other investors spread risks by holding less than 1% of a company’s shares, the three dominant investment fund managers—each holding up to 3% to 8% and together up to 17.6% of these companies’ shares—now have the most influential voting power at the corporations’ annual assemblies or in their direct engagement with top management. Their influence has since long not translated into pressure for corporate practice to adopt goals other than maximising profits.

The enormous expansion of the investment fund industry over the last decade, its interconnectedness with corporations, and the growing amounts of bad corporate loans, could easily end up in a new financial and broader crisis.

The consolidation of power by the major investment funds undermines competition among corporations in the same sector, because funds are dominant shareholders of competing conglomerates, which entices them to support similar corporate strategies. Moreover, the funds are increasingly following an index, valued according to stock-market price based on buying and selling of shares and profitability, with little assessment of corporate behaviour on the ground.

The enormous growth of the investment fund industry, which is requiring more corporate bonds to create funds, is behind a new corporate bond bubble that is likely to burst, having reached $ 10.17 trillion in 2018.

Too much money from (institutional) investors is seeking high returns and corporations are keen to cash in, including those with little or no profitability (‘junk bonds’). The riskier the business, the higher the interest rates that attract investors. Once the economy slows down and these so-called ‘zombie corporations’ start to default on their loans or bonds, investors might sell off massively. The interconnectedness and ripple effect, including the growing bad loans, could easily end up in a new financial and broader crisis.

Sidelining society and the environment

The concentrated investment industry has created even wider distance between the ultimate financier, i.e. the investor who is putting money into the investment funds, and the impact of corporate operations on society and the environment.

Investment fund managers buy shares and/or bonds from hundreds of corporations to be part of one ‘fund’, and follow this process to create hundreds of such funds, which are then offered to investors.

The sheer number of corporations included in one fund makes it too costly, according to fund managers, to scrutinise the on-the-ground impact of each the investee corporations. The funds only publicise a few of the corporations included in a fund, making it difficult to scrutinise all of them by the ultimate financiers.

Moreover, the large investment fund managers outsource their voting rights to proxy corporations, such as ISS and Glass Lewis, which prioritise voting in support of management and profit-making strategies that result in the highest value for shareholders and against resolutions for more responsible behaviour. As a result, they have allowed corporations to ignore the interests of workers and communities and concerns about climate change.

BlackRock’s CEO may have written an open letter in 2018 telling corporations that they have to show ‘a positive contribution to society’ but only in January 2020 did he wrote a, widely publicized, letter to CEOs announcing initiatives mostly for better (allowing) scrutinizing climate and sustainability risks of the companies BlackRock chooses to invest in. Behind closed doors, however, BlackRock has argued and lobbied against EU laws that provide clear definitions of green investments and oblige the disclosure of social and environmental risks or impacts of its funds.

A Dutch Bank, ING, which sells these investment funds to individual customers, even advertises that they can sleep while the bank manages their money. The information focuses only on how much profit their investment funds are making. Yet studies show that in the case of Dutch banks, the investment funds offered to their clients were financing abusive palm-oil companies.

Recently, environmental campaigners have started to confront investment funds’ responsibility for financing destructive practices. Friends of the Earth (US), for example, has attacked BlackRock, for investing billions in corporations that contribute to climate change, environmental destruction and violations of human rights, such as oil and gas corporations, mining corporations and palm-oil corporations.

Other key financial players that provide services to corporations

- The decision-making and the cost of financing corporations crucially depends on credit-rating agencies, which assess the profitability of corporations. They are paid by the corporation they analyse—a conflict of interest. They are also not currently legally obliged to assess social and environmental impacts

- Stock exchanges admit trading of a company’s shares, and are themselves for-profit corporations.

- The growing privatised pension funds have been part of the push to high shareholder value given that they invest in company shares and expect up to 7% return, with no responsibility for the consequences.

- Insurance companies protect corporations not only against damage and theft, they also provide insurance to companies’ CEOs for any wrongdoing and potential legal costs. In order to keep down the price of insurance premiums, insurance companies invest trillions of dollars in long-term financial instruments.

- Perhaps the most predatory players in the financial industry are the hedge funds and private equity funds (PE), often based in secrecy-bound jurisdictions and tax havens, and barely subject to EU or US regulation.

- Hedge funds are run by private asset managers earning high fees for providing high short-term returns from highly-speculative investments with money from very rich investors, including private pension funds.

Financialisation of everything

Financialisation of energy and food

The financial industry has also encouraged corporations to embrace increasingly complex financial instruments as a way to safeguard their profitability but which has had a knock-on effect on the wider economy and society. So, for example, in order to support large corporations in avoiding risks of financial loss or price variations (‘hedging’), investment banks developed derivatives (also known as swaps, futures/forwards, options), which are contracts that determine prices based on bets of prices in the future. Derivatives’ contracts are still mostly traded off exchanges (‘over the counter’, OTC) away from the public eye, and have doubled in value since the financial crisis, with up to $640 trillion notional amounts outstanding. These can go dangerously wrong as the financial crises demonstrated and have consequently been called ‘financial weapons of mass destruction’.

The most traded derivative is related to interest rates, sold as an insurance against raising interest rates. Banks have been accused of not explaining that these ‘swaps’ also can lead to corporations, municipalities and even farmers to being forced to pay the banks when the interest rate does not raise but goes down—which it did dramatically following the financial crisis. In the Netherlands, the banks even imposed such swaps on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that took out loans: no swap, no loan, even though SMEs knew little about the potential risks and ended up paying a very high price. In other words, bank services may end up serving the bank more than its corporate clients, which have to pay up.

In the case of commodity derivatives, their trading on and off commodity exchanges significantly determine prices of key commodities like oil, gas, minerals, wheat, and also products like coffee and cocoa. These markets have many financial players, setting up the infrastructure for the trading, designing the derivatives contracts, providing analysis, and facilitating the trade for hedging and speculation.

In theory, commodity derivatives guarantee a certain price and delivery date for selling by producers and buying by processors of energy or food commodities. Yet the supply and demand of contracts on commodity exchanges determine the price partly based on bets about future production and partly on the role of speculators, which does not relate to production costs. Nor do those who trade derivatives have any obligation or responsibility to take into account how these commodities are produced or consumed. It is no wonder, therefore, that increasing carbon emissions have not stopped trading in fossil-fuel energy derivatives or ensured that farmers are properly remunerated. In July 2019, 16 NGOs wrote to the London Metal Exchange to expose its dismal ‘responsible sourcing’ policy.

A post-2008 campaign in the EU challenged commodity price speculation after huge price spikes caused hunger riots from 2006 to 2008. It won partial legislative victories in 2014 but by the end of 2019, however, the EU law was under threat of being rolled back. Large oil- and gas- producing and trading corporations, such as Shell, have increasingly engaged in speculative trading. The question is whether this allows them to manipulate fossil-fuel prices so that renewables become less financially attractive.

Financialisation of corporations

The pressure for high profitability has not just ignored environmental and social issues, but has also critically changed the very nature of business models. It has led corporations investing their profits, or even the money from shares and bond issuance or loans, in the financial markets and offshore, rather than in their long-term future, e.g. innovation research for a just transition, or paying taxes and increasing the salaries of lower-paid staff—which might help limit growing inequality.

The big tech companies, for instance, have invested an estimated $ 1trillion offshore, half of it in corporate bonds, while borrowing close to $ 110 billion at lower interest rates.

Some corporations have even moved into providing their own financial and investment services. Supermarkets like Tesco and Carrefour, for example, offervarious banking and insurance services, commodity traders such as Cargill provide credit and derivatives services to farmers, and car manufacturers’ financial subsidiaries provide credit, insurance and leasing services.

Evidently, these financial services facilitate the purchase of the new products or services, sometimes with unexpected costs to consumers. Some companies are increasingly getting their profits from financial activities.

The tech giants have also initiated financial services and invested in fintech. Amazon has amongst others invested in Greenlight Financial, which allows children to have debit cards with parents controlling their online spending through an app.

The latest corporate financialisation initiative is Facebook’s proposal to issue a digital currency, the Libra, managed by a separate corporate body and using blockchain technology. These IT companies’ goal might not be the financial services as such, but the data they can obtain about their customers’ purchases and transactions.

The doom scenario

Corporations that can readily obtain financing—bolstered by and dependent on loans, blinkered share values on stock exchanges, favourable credit ratings, and protected by insurance companies and derivatives—have little incentive to undertake a swift transition and stop abusive social and environmental practices even if campaigns expose them. Rather, increased share and bond holding intensifies the pressure on corporations to raise short-term revenues from exploiting their value chains.

The overriding pressure can be seen in the case of Unilever, whose CEO Paul Polman started some more sustainable production initiatives and even did away with short-term quarterly financial reports. However, once Kraft Heinz made a hostile take-over bid, Unilever quickly returned to putting shareholder value first, including borrowing money to buy back shares and embarking on a new cost-cutting programme.

The dangers of the financial industry’s lack of responsibility for assessing social and environmental impacts, and its pressure on corporate short-termism, are now starkly exposed by the climate crisis.

Since 2015, a group of central bankers in the Network of Greening the Financial System have warned that carbon mispricing and climate change could result in financial instability or crisis. Climate disaster will cause, for instance, droughts that reduce agricultural production and storms that destroy commercial real estate and homes; at the same time the need for a swift reduction in the use of fossil fuels and related regulations will affect the production of many industries.

This will result in unpaid loans, falling prices of shares and bonds, massive withdrawal from investment funds with shares in fossil-fuel based industries, and extreme price volatility of mispriced derivatives. This would affect everyone, even small savers or pension funds.

Some supervisors include such a doom-laden scenario in ‘carbon stress testing’. The financial industry lobby, however, has been stopping necessary change—and even opposing EU laws to disclose whether or not they are assessing the negative climate, environmental and social impacts of the corporations in which they are investing.

The industry prefers to adhere to voluntary initiatives such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Principles on Responsible Banking or the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) but, as BankTrack has noted, banks that signed the 2003 Equator Principles, still refuse to disclose damaging projects they are financing—arguing that this is to protect their clients’ confidentiality.

Slowly, some shareholding investors see the future devaluation of fossil fuel-assets and are pressing corporations to take action against climate change and new EU laws incentivises them to do so.

New options for campaigns

The financial industry has successfully used complex structures and well-resourced lobbyists to remain unaccountable for its impact on people and the planet. Reforms made following the financial crisis have not stopped it from servicing corporations with abusive practices and further financialising the economy and society.

Civil society organisations (CSOs) have had some success in campaigning against the financial industry’s services to such abusive corporations and projects.

The industry’s continued wide range of financing instruments , however, has allowed corporations to ignore campaigns and undercut myriad voluntary initiatives. This points to the need to push for sanctionable, legally binding measures on, and the prohibition of, many financial players and instruments in the financing and shareholder value chain.

Public anger against growing inequality and climate change could lead to legislators and regulator’ willingness to take bolder action, or electing more radical politicians who can implement alternative financing systems.

One key priority for reform is tackling structural problems such as too-big-to-fail banks and the rapidly expanding but under-regulated investment industry. Why should they be allowed to be so large and make collective profits of hundreds of billions without any obligation to finance a just transition? Weak competition policy regulations as well as neoliberal trade and investment agreements allow these financial giants to expand and help corporations to become ever larger and more concentrated, taking no social and environmental responsibility.

The financial sector needs to be radically reviewed in order to serve society through smaller banks and financial services that are democratically accountable.

There are at least six urgent reforms:

1) Change laws so that the banking sector is made smaller and diversified, investment funds are strictly regulated and reduced, and hedge funds are eliminated.

2) Create a public rating agency or require private rating agencies to investigate abusive practices and harmful impacts on environmental or social sustainability by the corporations they rate.

3) Impose penalties on investment banks that issue shares or corporate bonds of abusive and destructive corporations.

4) Regulate stock exchanges to require prospectuses or reports to disclose the social and environmental impacts of listed companies, and prohibit listing of corporations with a record of bad practice.

5) Stop unsustainable energy and food commodity prices being set by derivatives trading and speculation, basing them instead on sustainable production costs.

6) Prohibit ‘socially useless’ activities such as high frequency trading and algorithm-based trading, lending/borrowing of securities to speculate, asset stripping of companies by private equity funds, and lending to hedge funds that practice speculative extractive financial instruments.

Experience has shown that achieving meaningful binding laws depends on a prolonged and major fight in the corridors of power against a hugely powerful financial lobby. Even after achieving a legislative victory, campaigning and advocacy need to prevent the financial lobby from manipulating the regulator’s technical standards and thus de facto defanging the laws.

Tackling the financial stronghold will be a key step in stopping corporations with abusive and destructive operations.

Importantly, the campaigns should demand that supervisors and regulators have a legal mandate and resources to enforce strict financial regulations, support alternatives and are accountable to the public.

Regulatory change will not happen without stopping the financial industry’s efforts to weaken or prevent legislation and regulations. The #ChangeFinance campaign managed to secure pledges by 576 European Parliament candidates to distance themselves from the financial lobby. There have been follow-up actions but there needs to be more emphasis on publicising the negative impacts if the financial industry gets its way. This should allow more space for citizens’ voices and highlight many existing or proposed alternatives.

Proposed regulatory reforms include developing a diverse financial sector to finance a just transition. Responsible cooperatives, ethical banks and democratically governed public banks should become attractive alternatives for citizens and companies alike.

The financial industry has become more a master than a servant, extracting value from corporations at any price. Tackling its stronghold will be a key step in stopping corporations with abusive and destructive operations, and should be part of untangling of chain of irresponsible service industries so as to speed up the transition to sustainable and equitable societies.