This essay is part of the book Public Finance for the Future We Want, you can find the entire collection of essays here.

The financial crash of 2007 created unexpected opportunities for proponents of democratically controlled public banks. Before the crisis, finance was one of the most privatized and deregulated sectors in the economy. But with this house of cards going down, things changed dramatically. The scale of public support from central banks, governments and tax payers that was required to keep the financial sector from disintegrating was unprecedented. Trillions were thrown at banks and financial markets. Ten years later many banks are still too big to fail and financial markets’ stability is dependent on central banks buying up huge amounts of assets from investors.

In response to the crisis, some banks had to be wholly or partly nationalized, such as the Royal Bank of Scotland in the UK, ABN AMRO and the Volksbank in the Netherlands, Bankia in Spain, Commerzbank in Germany and Belfius in Belgium, to name just a few. Governments nationalized these banks reluctantly. Anger with bailouts for banks was widespread but this did not translate into broad support for social movements calling for their democratization. Nevertheless, many opportunities remain and there is a convincing case for public mandates and diversified board representation to ensure banks invest in our communities, public services and the transformation towards a low-carbon economy in a socially just way.

This chapter explores strategies to democratize a nationalized bank by looking at the ‘Belfius is ours’ platform created by NGOs, social movements and labour unions in Belgium to promote the democratization of this bank. The platform’s manifesto calls for a broad societal discussion on a new public mandate, ownership, accountability and governance structures for the bank.1

Understanding our past

In 1860, the Belgian state created the Gemeentekrediet (Communal Credit). The goal of this public banking institution was to enable local governments to gain access to credit at affordable rates. If a local government wanted to take out a loan, it also had to become a shareholder of the bank, eventually making them owners of that bank.2 After WWII the bank started to take deposits from the public and developed a network of local branches.

In the 1990s, the Communal Credit bank started to diversify its activities and embarked on a process of privatization, internationalization and spec- tacular growth. This process began with the start-up of wealth manage- ment activities in Luxembourg in 1991; a year later the bank owned 25 per cent of Banque internationale à Luxembourg. In 1996 the Communal Credit bank merged with its French equivalent, Crédit local de France, and was called Dexia. In 1999 Dexia made its entry at the stock exchange and by the early 2000s the bank was active in the US, Israel, Turkey, Spain and Italy.

In the following years Dexia merged with an Italian bank and integrated various Belgian financial institutions. One of them was BACOB, a cooperative bank in the hands of the Christian labour movement, which would have huge political implications in the aftermath of the crisis, as we will see. By the early 2000s Dexia was a private international banking group, but the Belgian local governments and the ‘coopérants’ (members) of the late BACOB were the most important minority shareholders.

Dexia’s strategy was twofold. The large deposit base of its Belgian operation served as a stable source of financing for the loans made in France. Further, this deposit base allowed Dexia to borrow at low cost on financial markets to become a global financier of local governments,3 including with risky financial products to local governments in France and Italy (e.g. interest rate swaps).4 Dexia also participated in the infamous American subprime mortgage speculation.

Dexia had made itself extremely dependent on the continuous willingness of creditors to lend billions in short-term loans. When in 2007 the bursting American mortgage bubble provoked distrust, that willingness faded. On 30 September 2008 Dexia was bailed out with a €6.4 billion partial recapital- ization by the Belgian, Luxembourg and French governments. The 800,000 coopérants5 of the former bank of the Christian labour movement and the local governments participated in the recapitalization as shareholders, borrowing money from bankrupt Dexia.

Privatization pressures

Dexia would fall a second time in 2011, after investing heavily in the government debt of southern European countries. As the Euro crisis worsened and these countries came under increasing pressure from financial markets, Dexia lost the faith of its creditors and, with it, €80 billion in short-term funding and deposits. On 11 October 2011 what remained standing in Dexia’s Belgian operations was completely nationalized for €4 billion and would later be rebranded as Belfius6, without any consultation with parliament, let alone popular debate.

Belfius underwent a severe restructuring. After the nationalization in 2011 the number of employees was reduced by 20 per cent and for the following three years 15 branches were shut down annually.7 The bank became profitable again and was valued at €6-7 billion in 2015.8

In 2016, an expert report commissioned by the finance minister Johan Vanovertveldt raised awareness about the importance of ‘the provision of strategic services to the Belgian economy, such as payment services, credit to … households, the commercial sector and/or public authorities’.9 The two biggest banks in Belgium are foreign-owned and the top four control more than two-thirds of the sector.10 Belfius is the fourth largest bank, so its transformation had serious implications for the sector.

Both the government and the management of Belfius were in favour of privatization and in December 2016 the former planned to introduce the bank on the stock exchange, but to remain a majority shareholder. It seemed the government was looking for a middle way between outright privatization and government control over strategic areas as recommended by the expert group.

Entry on the stock exchange was set for spring 2018, but the political com- plexity of Belfius stood in the way. There was a lot of political pressure to compensate the 800,000 coopérants for at least part of their losses due to the nationalization, which this move was supposed to fund.11 The European Commission disapproved of such a compensation scheme, however. Later that year the government cancelled the privatization.

To this day the government has not acknowledged Belfius’s crucial role in servicing the public sector and the public overall. The bank’s growth strategy could focus more on its historical role of financing local governments and the non-profit sector. Loans to the public sector represent nearly one third of the bank’s loan portfolio and Belfius financed 70 per cent of all loans to local governments in 2017.12 And while Belfius’s lending and investment criteria do not include environmental protection or human rights and labour issues,13 it is one of the few banks that have almost completely stopped lending to the fossil-fuel sector.14

At odds with this more public orientation are the bank’s efforts to boost its financing of local private businesses and to expand its insurance business.15 Huge investments in rolling out digital applications for its clients also reflect commercial tendencies, as these tools are used to cut costs, close local branches, decrease staff and demand more flexibility of workers at the bank.16

Ownership, public mandate and board models

The platform ‘Belfius is ours’ was born in 2016 to promote open debate about the future of the bank. Its manifesto argues that the bank should pri- oritize serving society and should operate on the basis of a public mandate.

The platform started by criticizing the government’s plans for full or partial privatization. Only full public ownership could allow fulfilling a public mandate and foster financial stability over private profit maximization.

Emphasizing stability over profits would free up resources for more productive and socially useful loans, and deliver a variety of other financial services at cheaper rates. Public ownership, however, is not enough and needs to be accompanied by democratization of bank governance and accountability towards personnel, clients and citizens.17

Box I

Public banks from North Dakota to Finland

There is a wide variety of models of state ownership, and large public banking sectors exist in very different countries such as Brazil, India and Germany. One example from the United States is the Bank of North Dakota, which provides loans to build schools and to finance local public infrastructure projects. It also works together with oth- er local banks and credit unions to provide loans for farmers and mortgage loans. The bank finances its activities with deposits from local governments. An independent management runs the bank and is being overseen by a committee of local political representatives.18

A different example is that of Finnvera, a Finnish public bank that has a mandate to support small and medium enterprises and the internationalization of larger businesses. It has a market-oriented and less social mission (some NGOs have criticized its international projects19). The supervisory board controls the strategy of the bank and is the most powerful decision-making body. Members include parliamentarians from different parties, academics, business feder- ations, a trade union and a representative of the bank’s employees.20

These differences aside, however, the role these banks play in their domestic economies is generally similar: public banks tend to (1) provide patient money and expertise to their regional economies, (2) they compensate the up and down turns of markets with their long- term orientation, and their capacity to provide growth-boosting liquidity in times of crisis, and (3) they play a large role in providing access to basic financial services to low-income households.21 Overall public banks have been highly stable: in 2016 the top nine of the safest banks in the world were public banks.22

Box II

The German Sparkassen model

In order to demonstrate the opportunities offered by public banks, as well as to show how things can go terribly wrong, we will discuss in more detail one of the most interesting and well-developed models: the German public banks.

Germany has a large network of local public savings banks, the so- called Sparkassen. According to German law, these Sparkassen have to stimulate savings, lend to small and medium enterprises and promote financial inclusion. The more than 400 Sparkassen form a network that pools resources for shared information technology infrastructure and liquidity. They also have an interesting ownership

and governance model. They are legally independent from their local authorities and are public law institutions. No one owns the assets of the bank. Municipalities act as the responsible institution, but have no right to sell the bank or distribute profits. A supervisory board is composed of municipalities and other local stakeholders; its task is to ensure the bank fulfils its public mandate.23

This local network is complemented by the Landesbanken, Germany’s regional public banks. These are partly owned by the regional governments and partly by Sparkassen. Their role is to support the domestic industrial sector with loans, access to financial markets and investment management. They also invest surplus deposits from Sparkassen and help them to manage liquidity. Politicians have direct control over Landesbanken and their profits.

Finally, there is another state-owned bank that operates across the German territory: KfW. It functions as a public investment bank that supports local business through the Sparkassen and supplements German development cooperation.

Despite their significant past contributions to society, the demise of some of the Landesbanken demonstrates that public ownership is no guarantee that banks will prioritize their public mandate. In an effort to create a more ‘competitive market’ between private and public banks starting in the 1990s, the Landesbanken lost their state guarantee and were pushed to increase their profitability. This led some of them to go beyond their original mission and field of expertise and to invest in highly profitable, but complex and risky financial products such as mortgage-backed securities. This exposed them to the crash in the market for American subprime mortgages.24 The more prudent Landesbanken that did not lose as much in the crisis were often the ones where the Sparkassen had a more direct and dominant role as co-owners.

Public banks are a powerful economic tool and can play an important role in achieving socially just and ecological development. However, the mere existence of a public mandate is no guarantee, especially when they are being pushed to mimic private banks and focus on profit maximization.25 Nationalized banks need democratization instead of privatization.

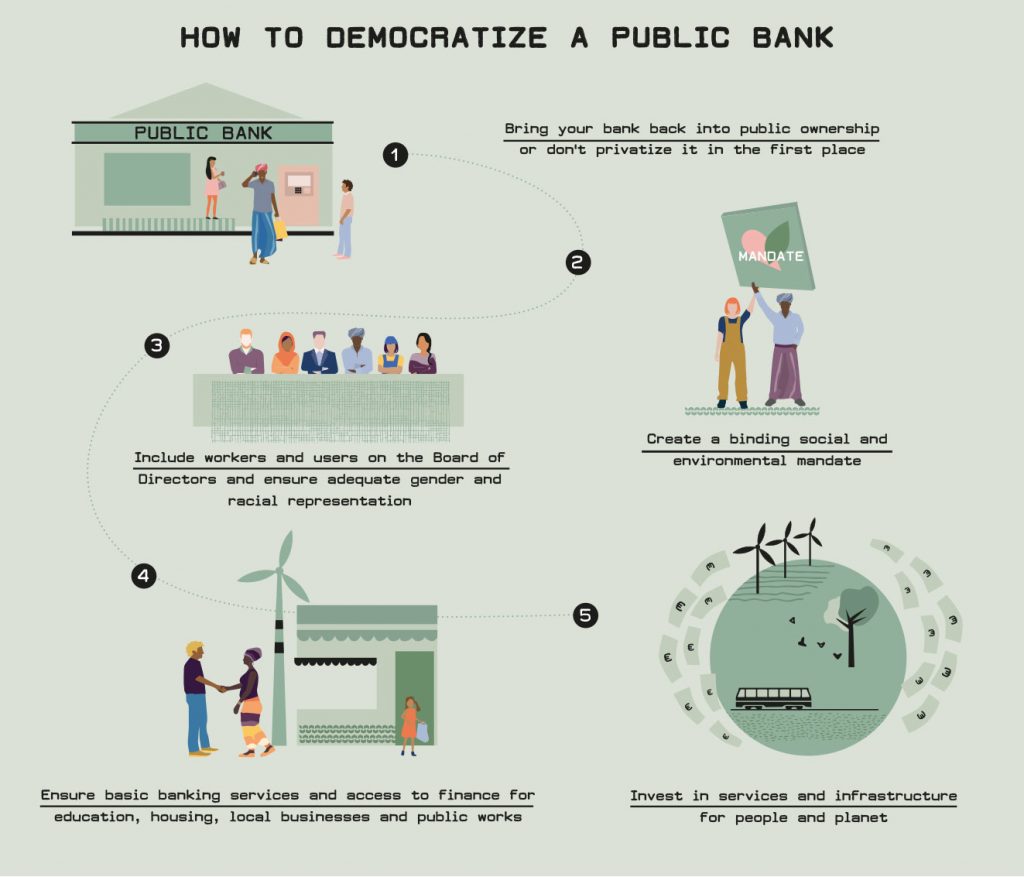

Democratizing public banks

Democratic control over public banks has two components. The right structures need to be in place, but there is also a need for a broad base of support from society. The modalities of public ownership and the governance structures are fundamental. A public bank needs checks and balances, tying everyone involved in the bank (management, owners, supervisory committees, workers and the rest of society) to the public mandate. The case of the Sparkassen is again interesting: its public mandate is written in law, municipalities act as responsible institutions but have no access to the profits of the bank, and the supervisory board, which represents different local stakeholders, is tasked to oversee whether the management of the bank respects the mandate. The authority of the supervisory board is a crucial point, as illustrated by the case of Finnvera: although its mandate does not stress ecological or social goals, the bank is governed by a multitude of societal and political stakeholders. Another interesting example is the Banco Popular in Costa Rica, which is owned by workers and additionally controlled by government representatives. Its highest governing body is the workers’ assembly covering 10 socio-economic sectors and representing 20 per cent of the country’s population.

Each public bank has its advantages and flaws and its mandate and governance structures must be assessed within their specific contexts. Nevertheless, existing public banks are sources of inspiration if we want to imagine what a democratized Belfius could look like. For example, the need to make the transformation towards climate-friendly societies calls for large-scale investments, especially in public infrastructure. With its expertise in financing the public sector, it could play a crucial role in such a programme. Instead of trying to sell as many investment funds to its clients as possible, it would serve society better if Belfius focused on facilitating public, cooperative projects co-organized by local governments and clients that act in the public interest. The market share it gained in financing the private sector can be put to use by extending this strategy towards lending to SMEs and other businesses. Furthermore, Belfius still has a large network of local branches, despite several closures, a resource it should put to use by making sure everybody has access to basic financial services.

The ‘Belfius is ours’ platform advocates for changing the structure of the bank through a public law that would split national operations and the network of local savings banks. The national branch would finance larger public infrastructure projects, pool liquidity, host information technology infrastructure and public payment services infrastructure for the local banks. The savings banks operating locally could finance smaller municipal projects, SMEs and provide households with access to basic financial services. The federal, regional and local governments could share the responsibilities for overseeing the different parts of Belfius and create supervisory boards on all three levels. They could make them the most important decision-making bodies and mandate them to ensure the bank fulfils its role, following the principle of subsidiarity. To give the people who can be affected by the activities of the bank the best access to decision and control mechanisms, local supervisory boards should take precedence over the national level. The supervisory boards should be composed of different stakeholders like employees, clients, academics and other public interest organizations.

Even with all these structures in place, people in different positions in government, the bank and other stakeholders need to be convinced of the importance of the public mandate. Public banks are currently forced to operate in a context where implementing a public mandate is not seen as a legitimate goal for a financial institution. Most other banks, the regulators and policy-makers see profit maximization as the norm.27 A change in ownership will therefore only lead to progressive and durable societal gains if it is accompanied by a change in the political outlook of those in charge and, ultimately, in its day-to-day operations.

This proposal is just an illustration of another possible future for Belfius. Parliaments, city councils and citizens should decide what should happen with their nationalized banks. In order for this to happen society has to mobilize around them.

The platform ‘Belfius is ours’ aims to bring together stakeholders like workers, NGOs and social movements working on social and environmental issues to build support. In 2018 the platform convinced 30 local governments, including most cities in the southern region of Belgium (Wallonie), to pass a resolution to keep Belfius public. A lot of ground still needs to be covered to steer towards a public mandate and democratization of Belfius. Meanwhile with the climate crisis fuelling unprecedented demonstrations, more people are discovering that Belfius could play a crucial part in a socially just transformation.

About the author

Frank Vanaerschot has worked at FairFin since 2010, first as a campaigner and now as research co- ordinator covering debates on financial regulation, public ownership of banks, and fossil fuels and min- ing investments by banks. He is one of the initiators of the platform ‘Belfius is ours’ that promotes the democratization of Belfius bank.

With contributions from Yelter Bollen, who has a PhD in political science at Ghent University and vol- unteers at FairFin.

Notes

1 See website of the platform “Belfius is ours”: http://www.belfiusisvanons.be/ (accessed 5 September 2018).

2 Le Moniteur belge (1860) Rapport au roi. Le moniteur belge nr 343.

3 Dexia Bank Group (2002) ‘Annual report 2002.’ Dexia Bank Group, Brussels, p. 13

4 Saurin, P. (2013) L’état sacrifie les communes piégées par les emprunts toxiques. CADTM. Available at: http://www.cadtm.org/L-Etat-sacrifie-les-communes (accessed 3 September 2018)

5 Since this recapitalization was very risky, the government made the controversial decision to

apply the deposit guarantee scheme to the cooperants of the Christian labour union.

6 The group Dexia became a “bad bank” meaning that the banking group would go bankrupt and

generate financial instability, because many counterparties of the bank would face immedi- ately huge losses. The “bad bank” Dexia Holding is being kept alive with the sole purpose of try- ing to minimize the losses from the loans and other financial products on the balance sheet of the bank. It is mostly owned by the French, Luxemburg and Belgian governments. They provide a decades-long guarantee of €90 billion to avoid a chaotic bankruptcy.

7 Fares, A. (2018) ‘Une banque publique pour les habitants et habitants de ’elgique’. Inégalités.be. Available at: http://inegalites.be/Une-banque-publique-pour-les?lang=fr#nb3 (retrieved 2 September 2018)

8 De Tijd (2017) Regering stelt Nomura aan voor beursgang Belfius. Available at: https://www.tijd. be/ondernemen/banken/regering-stelt-nomura-aan-voor-beursgang-belfius/9950147.html (retrieved 30 September 2018)

9 The high level expert group was largely composed of orthodox and influential members, including the former governor and another director of the central bank, with the exception of anthropologist Paul Jorion who worked on Wall Street in the early 2000s and warned of financial upheaval before the crisis. See High Level Expert Group (2016) The future of the Belgian financial sector. Brussels: Minister of Finance of Belgium. Available at: https://www.febelfin.be/sites/ default/files/InDepth/hleg_report_-_the_future_of_the_belgian_financial_sector.pdf, p. 58. (retrieved 2 September 2018)

10 Fares, A. (2018) Une banque publique pour les habitants et habitants de Belgique. Inégalités.be. Available at: http://inegalites.be/Une-banque-publique-pour-les?lang=fr#nb3 (retrieved 2 September 2018)

11 Meanwhile the European Commission had declared the inclusion of the cooperants in the deposit guarantee scheme to be a form of illegal state support.

12 Belfius Bank SA (2017) Annual report. Belfius Bank SA, Brussels. Available at: https://www. belfius.com/EN/Media/bel_RA2017_eng_tcm_77-152056.pdf (accessed 30 August 2018)

13 Bankwijzer (2017) Het beleid van Belfius. Available at: https://bankwijzer.be/nl/bankwijzer/bank- en/belfius/ (retrieved 2 September 2018)

14 Vanaerschot, F. (2017) Fossielvrije banken in de strijd tegen de koolstofzeepbel. Klimaatcoalitie, p. 29. Available at: https://gofossilfree.org/be/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2018/03/Onderzo- ek_divestment_Klimaatcoalitie.pdf (retrieved2 September 2018)

15 Belfius Bank SA (2017) Annual report. Belfius Bank SA, Brussels. Available at: https://www. belfius.com/EN/Media/bel_RA2017_eng_tcm_77-152056.pdf (retrieved 30 August 2018)

16 Bankwijzer (2017) Het beleid van Belfius. Available at: https://bankwijzer.be/nl/bankwijzer/banken/belfius/ (retrieved 2 September 2018)

17 Maurice Westendorp: ‘Winstmaximalisatie past niet bij de Volksbank’. MT.nl. Available

at: https://www.mt.nl/leiderschap/nieuw-leiderschap2/maurice-oostendorp-winstmaximalisa-tie-past-niet-bij-de-volksbank/558231 (retrieved 30 August 2018)

18 Dierckx, S. (2017) ‘Waarom de privatisering van Belfius een slecht idee is’. Minerva. p. 16.

Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/580dffc9f7e0ab87773f- c653/t/595d5d2244024313332958bc/1499290918523/20170705+Waarom+de+privatiser- ing+van+Belfius+een+slecht+idee+is+%28Sacha+Dierckx+-+Denktank+Minerva%29.pdf (retrieved 30 august 2018)

19 ECA Watch (2006) ‘Human rights and ECA’s: the Uruguayan paper mill case’.

http://www.eca-watch.org/publications/human-rights-and-ecas-uruguayan-paper-mills-case

(retrieved on 3 September 2018)

20 Macfarlane, L. and Mazzucato, M. (2018) State investment banks and patient finance: An

international comparison. Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose.

21 Scherrer, C. (2017) Public banks in the age of financialization. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited,

p. 3.

22 Global Finance (2016) The world’s 50 safest banks 2016. https://www.gfmag.com/media/press-releases/The-Worlds-50-Safest-Banks-2016 (retrieved 2 September 2018)

23 Greenham, T. and Prieg, L. (2015) Reforming RBS. Local banking for the public good. New

Economics Foundation, p. 40 https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/141039750996d- 1298f_5km6y1sip.pdf (retrieved 2 September 2018) Dierckx, S. (2017) Waarom de privatisering van Belfius een slecht idee is. Minerva. p. 26 https://static1.squarespace.com/static/580dffc- 9f7e0ab87773fc653/t/595d5d2244024313332958bc/1499290918523/20170705+Waarom+de+ privatisering+van+Belfius+een+slecht+idee+is+%28Sacha+Dierckx+-+Denktank+Minerva%29. pdf (retrieved 30 august 2018)

24 Greenham, T. and Prieg, L. (2015) Reforming RBS. Local banking for the public good. New Economics Foundation. p. 27. https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/141039750996d- 1298f_5km6y1sip.pdf (retrieved 2 September 2018) Scherrer, C. (2017) Public banks in the age of financialization. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. p. 249.

25 Greenham, T. and Prieg, L. (2015) Reforming RBS. Local banking for the public good. New Economics Foundation, p. 25-29. https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/141039750996d- 1298f_5km6y1sip.pdf (retrieved 2 September 2018).

26 Marois, T. (2017) How public banks can help finance a green and just energy transformation. Transnational Institute, Amsterdam, p. 5.

27 Scherrer, C. (2017) Public banks in the age of financialization. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, p. 253-254.