Charming Psycopaths

The modern corporation

An interview with Joel Bakan

STATE OF POWER 2020

28 August 2020

In 2004, a powerful documentary film, ‘The Corporation’, caught the political imagination when it was released at the peak of the alternative globalisation struggles that emerged following the protests at the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle. Based on a book of the same name, and using a witty and stylish mix of news clips, music and perceptive analysis, the film boldly challenged capitalism’s single most important player, the corporation.

The documentary won 26 awards, with even conservative commentators such as The Economist calling it ‘[a] surprisingly rational and coherent attack on capitalism’s most important institution’. To launch our collection examining ‘The Corporation’, the Transnational Institute went back to the film and books’ writer, Joel Bakan, a law professor at the University of British Columbia, to find out how he views the corporation today.

What is the corporation?

The corporation is a legal construct, indeed a legal fiction. It is not something created by God or by Nature, but rather a legally created and enforced set of relations designed to raise capital for industrialism’s large projects. Its main function is to separate the owners of an enterprise from the enterprise itself.

The latter is alchemically transformed into a ‘person’ that can bear legal rights and obligations, and therefore operate in the economy. The owners – shareholders – thus disappear as legally relevant, with the corporate ‘person’ itself (and sometimes its managers and directors) holding legal rights, and being liable when things go wrong.

It follows that shareholders’ only risk is to lose money if their share value declines. They can’t be sued for anything the corporation does. Moreover, to further sweeten the pot for their investing, the law imposes obligations on managers and directors to act only in shareholders’ best – that is, financial – interests.

The corporation is a legal construct, indeed a legal fiction.

The genius of it all is that this highly pro-shareholder construction provided strong incentives for many people, particularly from the emerging middle class, to invest in capitalist enterprise.

That was the corporation’s main purpose – to generate the huge pools of capital needed to finance large enterprises, railways, factories, and so on, that industrialisation made possible. It was, in effect, a crowd-funding institution.

What has the corporation become?

The corporation’s central institutional function – concentrating thousands, even millions, of investors’ capital into one enterprise – also created the potential for enterprises to become very large and powerful.

There were initially limitations on their power – caps on growth, restrictions on multi-sector involvement, competition laws, and so on – but over twentieth century these were weakened and eliminated.

Now companies can merge, acquire, and get bigger and bigger, accumulating ever more power with little to constrain them. As a result, they become these vast concentrations of capital that dominate not only the economy, but also society and politics.

They are not democratic and are legally compelled to serve their shareholders’ interests in everything they do.

So, you have these huge and powerful institutions, compelled by their institutional characters to pursue self-interest regardless of the consequences, bent on avoiding or pushing out of the way anything that impedes their missions – such as regulations, taxes, and public provision – creating wealth for anonymous and unaccountable shareholders, and with no democratic accountability to the people (other than their shareholders) affected by their decisions and actions.

What has changed in the 15 years since you wrote The Corporation?

A few obvious things. Big tech didn’t exist (at least not in the dominant way it does now) at the time of the first project. Climate change was a problem, but not yet the existential and immediate crisis we know it is today. The populist right was still on the fringes, globalisation was in full swing, and corporations – smarting from anti-globalisation struggles around the world, and worried about growing popular distrust and concerns about their expanding power – strategically changed their image and their game.

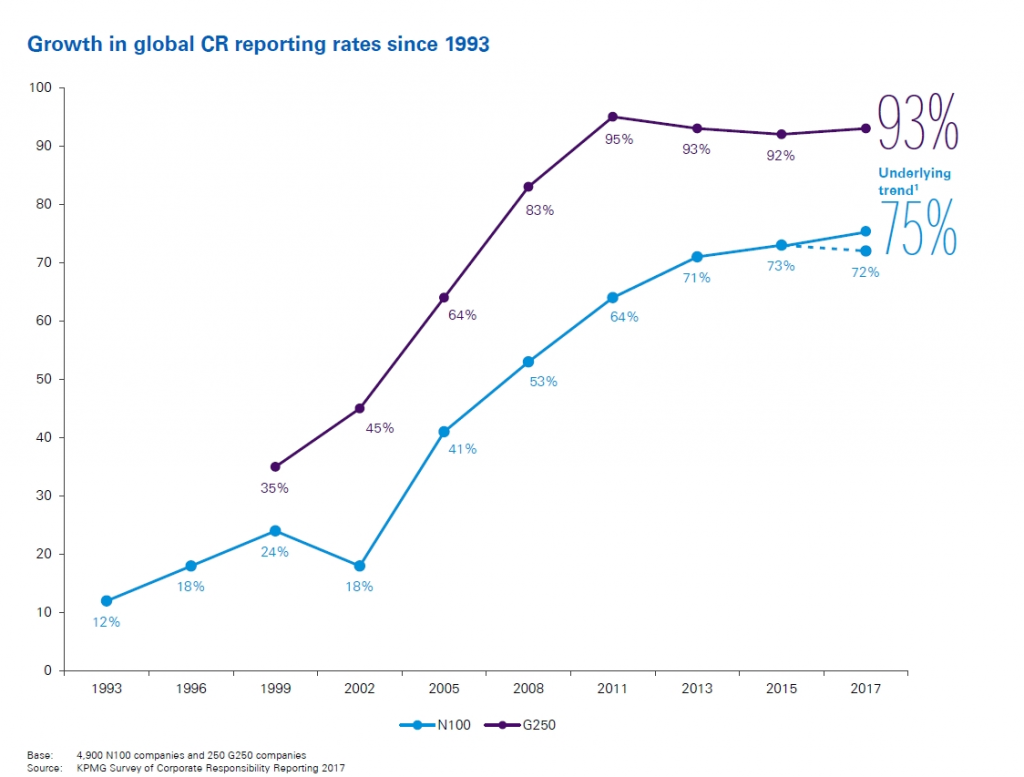

In terms of the latter, corporations began, around the time my first book and film came out, to make sweeping commitments to sustainability and social responsibility – to use less energy, reduce emissions, help the world’s poor, save cities, and so on.

Creative capitalism, inclusive capitalism, conscious capitalism, connected capitalism, social capitalism, green capitalism – these were the new kinds of buzzwords that came to the fore, reflecting a sense that corporate capitalism was being modified into a more socially and environmentally aware version.

The key idea, whatever rhetoric it was wrapped in, was that corporations had changed fundamentally, that while corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability had previously been located on the fringes of corporate concerns – a bit of philanthropy here, some environmental measures there – now they became entrenched at the core of companies’ ethos and operating principles.

Growth in corporate reporting by the top 100 and 250 corporations

Growth in corporate reporting by the top 100 and 250 corporationsWell, has it made any difference?

Yes, but not necessarily a positive one. The subtitle of my new book is ‘Why “good” corporations are bad for democracy’.

Let me explain. To begin with, despite all the fine rhetoric, the new corporation is fundamentally the same as the old one. Corporate law hasn’t changed. The corporation’s institutional make-up hasn’t changed.

What has changed is the discourse, and some of the behaviour. The new ethos is captured by the idea of ‘doing well by doing good’, finding synergy between making money and doing social and environmental good rather than presuming there’s conflict.

The further problem is that corporations are leveraging their new putative ‘goodness’ to support claims they no longer need to be regulated by government and that they can also do a better job than governments in running public services.

So now corporations make a lot of noise about their aim being to do good, far less about the fact that they can only do as much good as will help them do well.

The fact is, despite all the celebratory talk, corporations will not – indeed, cannot – sacrifice their own and their shareholders’ interests to the cause of doing good. That presents a profound constraint in terms of what kinds and amounts of good they are likely to do – and effectively licenses them to do ‘bad’ when there’s no business case for doing good.

The further problem – and this is the part about democracy – is that corporations are leveraging their new putative ‘goodness’ to support claims they no longer need to be regulated by government, because they can now self-regulate; and that they can also do a better job than governments in running public services, such as water, schools, transport, prisons, and so on.

Climate is an area where corporations have been particularly crafty. No longer can they plausibly deny climate change, so they don’t. Instead, they say ‘yes, it’s happening, we acknowledge it, but we now care, we can take the lead and provide solutions, we don’t need government regulation’.

Now, if you talk to scientists, they all say we needed to have adopted renewables yesterday to prevent cataclysmic scenarios, and that this will require massive state-led changes.

If you talk to the fossil-fuel industry, they say something quite different, something consistent with their plans to profit as long as possible from carbon fuels. They say we have time, that we shouldn’t and can’t get to renewables any time soon, that natural gas and fracking are good alternatives, that it’s all right that they continue to develop mega-projects to tap fossil-fuel reserves (including coal, like the Adani mine in Australia), that that they will take the lead on renewables.

That we should trust them – not governments – to sort out climate.

Environmental lawyers from ClientEarth in 2019 filed a high-level complaint accusing BP of misleading consumers in its latest advertising campaign, noting that the company spends less than four pounds in every hundred on low-carbon investments and 96 pounds on fuelling the climate crisis.

This new strategy is probably even more dangerous than outright denial. By purporting to be the ‘good guys’ now, they more subtly obfuscate and obscure truths and intentions, wielding their influence with governments and at climate summits to ensure their carbon-fuel-based business models remain largely unimpeded.

In my first book, the Corporation, I argued that if corporations were really people, they would be by their behaviour and traits be considered psychopaths. Now, as they put on a false face, they have effectively become charming psychopaths.

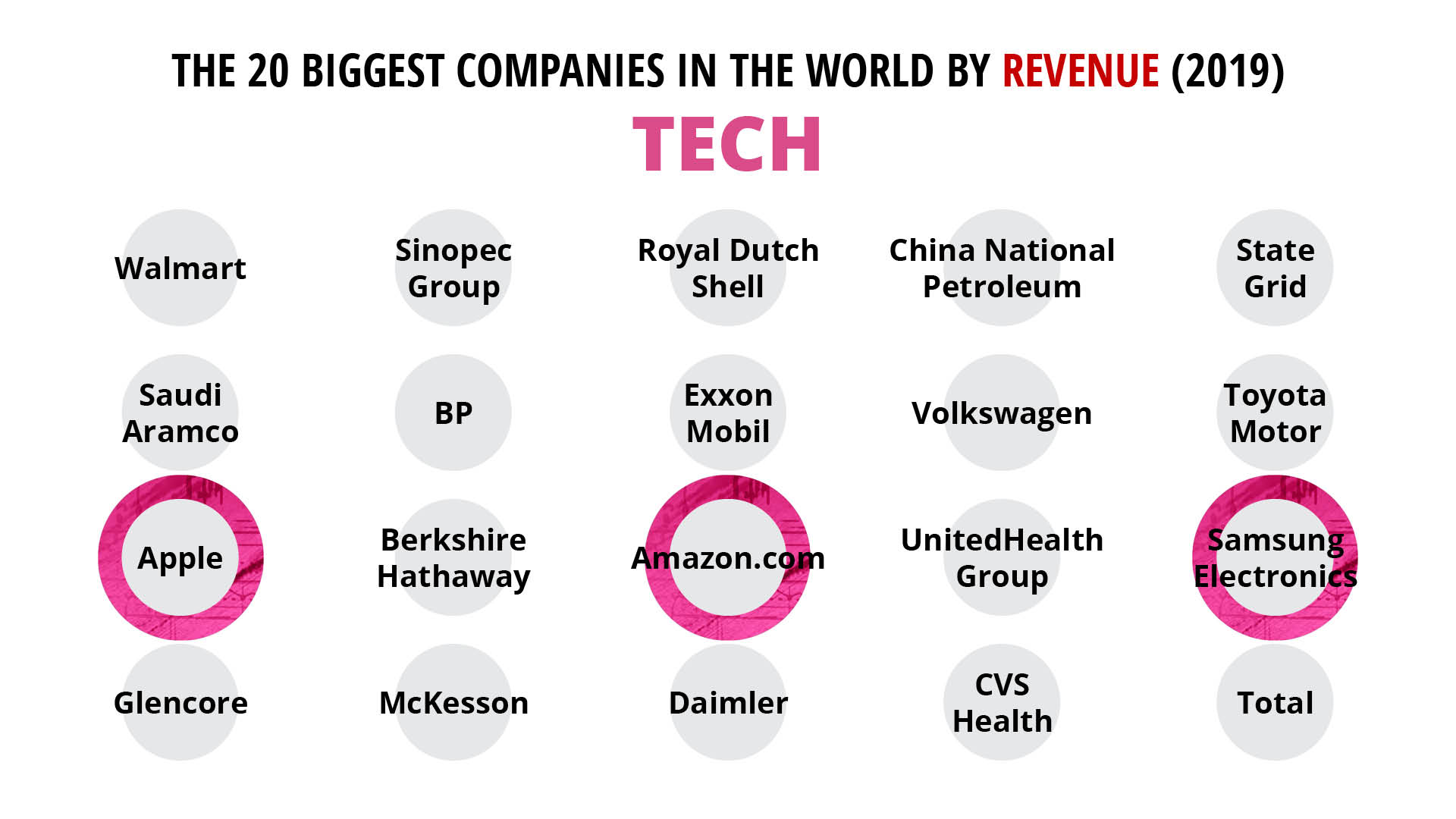

What difference has the rise of the digital giants made to the nature of the corporation?

When internet and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies are harnessed to the corporate compulsion to create profit, bad things can happen – and are happening. It’s true, as tech advocates say, that innovation and disruption are the result. But neither is necessarily a good thing. For example, the innovations of big tech are disrupting the policing of monopolies.

For many tech players, monopoly is built into their business models. Facebook, for example, has to be the place everyone goes for social connection. Amazon needs to be the platform for all shoppers and retailers. Google, the search engine everyone uses. The value of these companies is based on being the one place where everyone goes. That gives them a monopoly on the two things that have value in the tech space – attention and data.

It also incentivises them to go beyond their sectors, to invade and dominate other sectors – such as Amazon entering cloud-based computing and pharmaceuticals, Facebook becoming a major news hub and increasingly central to how election campaigns are run, Google pushing into urban planning (through Sidewalk Labs).

The problem is often thought about in terms of privacy but the real problem is control: how the data is likely to be used to control how we act, think, and feel.

Current anti-monopoly laws and regulators are too weak (a result of deregulation) and politically unmotivated to keep up, which is what has allowed these companies to turn into behemoths that stifle competition and have undue influence on politics and society – in short, to disrupt democracy.

Another problem is that corporations are collecting ever more data, triangulating it, graphing our every move and emotion, especially as all the hardware in our lives becomes internet-connected (through the ‘Internet of Things’) and the software becomes more sophisticated at monitoring and predicting our behaviour.

The problem is often thought about in terms of privacy – that our privacy is being invaded by the collection of all this data. But the real problem is control: how the data is likely to be used to control how we act, think, and feel in ways that are ultimately profitable to corporations.

The possibilities for employers controlling workers’ every move are already evident in, for example, Amazon’s micro-monitoring of warehouse workers’ performance. Similarly, insurance companies are starting to monitor life insurance policy-holders’ fitness and physiological data through wearable devices and so on.

And how does that affect democracy?

As corporations gain greater direct control over individuals through new technologies, it becomes more difficult – if not impossible – for democratic governments to regulate the relationship between corporations and private citizens.

When an insurance company has direct control of individuals it insures – knowing their driving habits, or whether they are fit, and adjusting rates or denying pay-outs on these bases – it becomes difficult for democratic institutions – regulators and courts – to protect individuals’ consumer rights.

When a platform like Uber uses technology to effectively circumvent the employment relationship (a regulatory construct designed to protect workers from the much greater power of their employers) it becomes difficult to protect workers.

Democracy is also affected by the rise of misinformation, hate, and incendiary speech, which is magnified by the internet and social media. That too is connected to big-tech business models. A company like Facebook thrives by getting more people engaged more of the time. More is better – and questions about truth, or the public interest, or democracy are simply irrelevant.

More generally, the rise of right-wing authoritarianism, which is happening through democratic electoral processes, is in large part a reaction to 40 years of neoliberal policies that have destroyed jobs and social provision, and thus lives and communities. Those 40 years of policies were – and continue to be – spearheaded by large corporations, which used their resources to lobby, fund elections, move and threaten to move operations in response to regulation and proposed regulation, roll back and avoid taxes, and so on.

It’s quite the two-step. They campaign to eviscerate governments’ capacity to deal with social and environmental issues, and then step in to say that they can do the work government has been rendered, through their efforts, unable to do.

Leaders of the ‘new’ corporation movement – the very companies claiming to care, to be socially responsible and sustainable – have been at the forefront of these campaigns. None of them has said, ‘social and environmental values are important, so let’s have more regulation and taxes to protect them’. Quite the contrary.

Corporations are now leveraging their supposed new persona to push back democracy, by claiming, as noted above, that they can regulate themselves in lieu of legal measures, and that they should be put in charge of social provision in place of public authorities.

It’s quite the two-step. They campaign to eviscerate governments’ capacity to deal with social and environmental issues, and then step in to say that they can do the work government has been rendered, through their efforts, unable to do.

The result is less government and more corporations in our lives and societies – meaning less democracy overall.

How have civil society and social movements responded to the rise of the corporation?

The last 20 years have seen a remarkable rise of organised and effective movements to push back against corporate power and the threat it poses to democracy.

More than 200 cities around the world have rejected water privatisation by re-municipalising previously privatised systems; indigenous peoples have won battles against extractive industries and for recognition of land rights and self-determination; the ‘movement of the squares’ swept through cities around the world in 2011 and included the Occupy movement; progressive politicians have won victories in cities like Barcelona and Paris in Europe, New York, Jackson, Seattle and Tucson in the United States, and Vancouver in Canada – along with many others.

>Graphic from TNI’s report, Reclaiming Public Services: https://www.tni.org/en/publication/reclaiming-public-services

In the United States, there was Bernie Sanders, an open socialist, making (in 2016, and again in 2020) a play for the presidency, and the thousands of progressive election campaigns he helped inspire, many successful – like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) and other progressive representatives.

And then there’s the new energy and urgency of surging activism around the world, mass movements demanding action on climate change, extractive industry projects, indigenous rights, against racism.

It’s all very positive and inspiring.

We have to be wary, however, of corporations’ attempts to co-opt this wave of resistance. They are certainly trying, working hard to make us to believe that they are the true change-makers; that our best path to a better world is to buy their ‘green’ products, support their social and environmental initiatives, follow their advice on recycling, reducing, and so on.

Companies and their CEOs take stands on various issues, and they increasingly form partnerships with non-government organisations (NGOs) like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Save the Children (SCF), Conservation International and inter-governmental organisations such as the various entities of the United Nations.

No doubt some good may come from all this, but it’s important to recognise that the same companies allying with NGOs, and taking up a stance on racism, immigration, or discrimination against LGBQT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer and Transgender) people are also lobbying hard to reduce government oversight, push back taxation, expand markets, cut social provision, and so on.

Is there a place for the corporation in the future?

I think there is a place for a financing vehicle for large projects that require large pools of capital, which is essentially what the corporation is. But it has to be understood as a tool, as a means, not an end in itself.

The corporation was created by government for that purpose, as a financing tool. Its virtue in incentivising investment – its legal mandate to create wealth without constraint – is also its greatest danger.

Because of that, it must be regulated, and it shouldn’t be used to deliver inherently social goods, and certainly not to help govern society. It is completely ill-equipped to do those things, being fundamentally self-interested and lacking democratic accountability to anyone but its shareholders.

Because of the corporation’s legal mandate to create wealth without constraint, it must be regulated, and it shouldn’t be used to deliver inherently social goods, and certainly not to help govern society.

We should also be thinking about using other kinds of economic organisations to create goods and services, such as cooperatives, or public institutions with public-interest mandates.

There is no evidence to support, and much to contradict, that that the ideal institution is always, or even usually or sometimes, the large for-profit corporation. Rather, corporations are best thought of as we might think about, say, a lawn mower. It has its uses. It’s very good at cutting the lawn. But you don’t want to use it to cut your hair or vacuum your living-room rug.

All of which may be an argument for shifting away from capitalism to some other kind of system – such as those imagined by democratic socialism, or the commons movement or indigenous cosmologies – where social and ecological ends are prioritised rather than the accumulation of capital.

Though something like that may be on the horizon, in the meantime we have to figure out how to rein in the dangerous tendencies of the corporations and capitalism we currently have, and to ensure they do not – as they may – turn out to be doomsday machines.

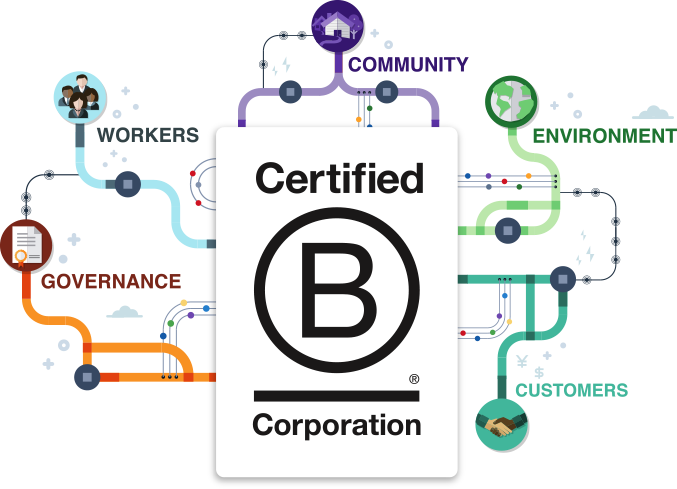

What about B-Corps or Benefit corporations? Are they a good step?

No. B-corps are not a solution and I have opposed them, including in my home province of British Columbia where the government took measures to recognise them.

Typically, a B-corp is nothing more than a certification by a private company (such as B-Lab) that a corporation meets certain social and environmental standards.

It’s not needed for corporations that are not publicly traded, which already have leeway to subordinate financial to social and environmental goals if they so wish. And for publicly traded corporations, even if they become B-corps (which, so far, no major one has), they’re still legally bound to prioritise shareholder value. A private certification doesn’t change the law.

So what B-corps end up being are, in effect, a privatisation of regulation, a prop for the ideology that corporations, through market mechanisms and private oversight, can protect and promote public interests. It’s not about democratically promulgated rules to control corporations, nor about state-backed enforcement mechanisms for such rules. It’s yet another velvet glove hiding the iron fist of neoliberalism.

Benefit Corporations are yet another velvet glove hiding the iron fist of neoliberalism.

A different approach is to reformulate the legal constitution of the corporation to include social and environmental goals as well as financial ones. Again, I don’t favour this approach.

One problem is that it will never subordinate financial goals to social and environmental ones – the latter will always be pursued only in ways that are compatible with the former.

The second problem is that indeterminate judgements about whether social and environmental goals are met – which should be pursued, how and to what extent – are placed in the hands of managers rather than democratically accountable regulators.

Third, the presence of this new kind of corporation would inevitably be leveraged, probably successfully, to push for more deregulation – the argument being that regulation is redundant when standards are baked into the corporation itself.

The problem is that the corporation’s sole reason for existing within capitalism is to incentivise investment. That will always entail prioritising returns on investors’ capital, rather than competing values fixed into the corporation’s legal nature. The imperatives of corporations within capitalism will always be capitalist imperatives.

We need to deal with the dangers of that dynamic democratically, through policies, laws, and regulation, rather than by tweaking the corporate form and effectively delegating regulatory functions to corporate managers and directors.

How do we get there?

I don’t advocate revolution because I believe existing democratic structures, however corrupt, can be reclaimed and repurposed, reunited with grassroots movements and the genuine needs and voices of citizens.

In the meantime, we need to do a lot of myth-busting to reveal the truth that corporations and markets can’t deliver the social and environmental goods we need; that democracy and democratic institutions must be revived.

We need to work with and in our communities, schools, and unions, to educate and inspire each other. To work with, become part of, and help elect progressive political parties, join and form movements, promote solidarity while celebrating difference.

We need to see ourselves as political actors, citizens, obliged to take part in and contribute to creating good and just societies. We need to accept that democratic governance is messy and uncertain, that it’s as much about the process of participation as it is about the resulting policies, and that it can only flourish in social conditions that nurture empathy and solidarity among citizens.