COVID CAPITALISM REPORT

K. Biswas

Illustration: Orijit Sen

14 October 2020

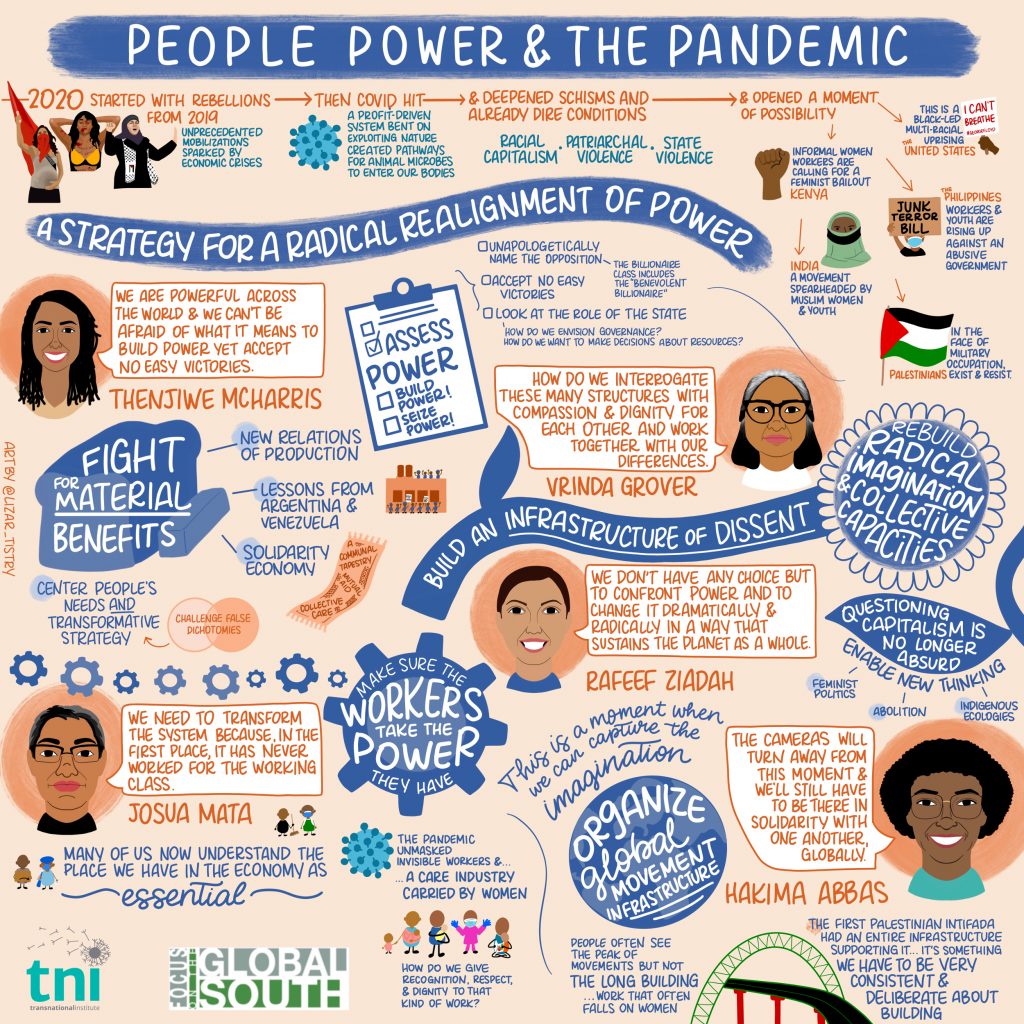

We will certainly all remember 2020 for the way it turned our lives upside down, but what will its long-term repercussions be on our political, economic and social systems? The virus may have been invisible to the human eye, but this spiky protein particle exposed like never before the fractures and flaws of our manmade systems, accelerating certain trends, and demonstrating the need for transformative change to protect our health and the health of this planet. Between April and July 2020, Transnational Institute hosted a unique set of 12 global conversations to analyse the fallout from COVID-19 and to articulate the changes we need for a better world. The webinars took place in collaboration with allied organisations and partners around the globe, including AIDC and Focus on the Global South. This critical report pulls out the main analysis from those conversations, with a focus on the proposals and solutions put forward by activists and experts worldwide. We hope this report helps citizens and social movements analyse the crisis, inspires transnational solidarity and works towards the emergence of a more just world.

Top Ten Takeaways

1. Internationalism – Social movements limit themselves by working within national boundaries.

For too long, activists have operated in silos – failing to provide platforms for each other’s struggles, build cross-national infrastructure and reallocate resources towards those most in need. The global nature of the crisis presents an opportunity to unite and fight – we must better understand the transformative power of solidarity, reach over divides, and reduce the disparities between richer and poorer nations.

2. Healthcare – Privatised healthcare systems cannot cope with pandemics like COVID-19.

Creeping privatisation of public health infrastructure and big pharma withholding access to medicines have impacted upon those most in need of life-saving healthcare. We must prioritise resourcing universal public health services across the globe that will best serve both patients and frontline health workers.

3. Neoliberalism – States have not learned lessons from the last great financial crash in 2008.

Government proposals to stimulate the economy after a global shutdown fail to consider existing social inequalities, which are likely to exacerbate in the aftermath of the pandemic. Rather than bail out CEOs and speculators, we should strongly invest in communities and workplaces, while addressing underlying structures of injustice.

4. Migration – The ‘border-security complex’ is expanding and normalising massive breaches of human rights.

The crisis has seen the increased demonisation and harassment of migrants, with access to asylum closing, displaced people being detained, and borders extending further. Civil society can help dismantle barriers and better champion migrant rights and the freedom to move by placing those with experience of migration at the forefront of campaigns.

5. Authoritarianism – Emergency powers handed to state authorities tend to stick.

New measures have given police and security forces unprecedented capabilities under the guise of public safety, yet these often curtail fundamental civil liberties – particularly of those already marginalised – and embolden authoritarian groups. The public should push for emergency laws to be transparent and temporary and seek to defend spaces of resistance when governments and vigilantes overstep the mark.

6. Ecology – The likelihood of future pandemics and climate chaos is rising.

Extractive industries and human expansion into wildlife habitats play a critical role in spreading disease and speeding up climate change. An immediate transition from fossil fuel reliance to localised renewable energy production, and moving away from commercial agribusiness towards more agroecological farming methods will help avert large-scale food, water and electricity shortages, create jobs, and allow humanity a chance to live a sustainable future.

7. Feminism – The women’s movement offers a transformative politics to address contemporary crises.

Industries with predominantly female workforces like nursing, cleaning and food production are underpaid and at risk, domestic labour is devalued, and under lockdown restrictions women have been targeted by state authorities and abusive partners. The women’s movement is advancing feminist democratic ideas worldwide through building new inclusive structures of power, and centring care and participation as the basis of social organisation.

8. Incarceration – Unsafe, overcrowded prisons unveil a crisis in the worldwide criminal justice system.

Across the globe, prisons lack basic provisions and support for those incarcerated – many of whom have committed minor, non-violent offences and predominantly come from poorer backgrounds. Society should make urgent moves towards decarceration – looking at community–based alternatives to detention, championing rehabilitation over punishment, defunding prisons and supporting those with experience of the criminal justice system to have a say over its future.

9. Technology – Big tech’s growing power poses an unprecedented threat to democracy and privacy.

As more of our work and social life moves online, states are paying technology companies vast sums for public surveillance, digital businesses are booming and storing unprecedented amounts of our personal data, while developing countries are being over–run or excluded from participating in the modern economy. Citizens should work towards helping to close the digital divide between poorer nations and major economies, bring tech titans under democratic control, and protect our privacy by reclaiming our data.

10. Universalism – Our human rights are being further eroded.

Across the globe, access to even the most minimal services – from social security and healthcare, to food, water, electricity and shelter – is denied to many, and in each continent there are states which seek to persecute marginalised communities. Activists will need to ensure that during an emergency the fundamental rights of all citizens are not just protected but advanced, forming the basis of the society which emerges from this crisis.

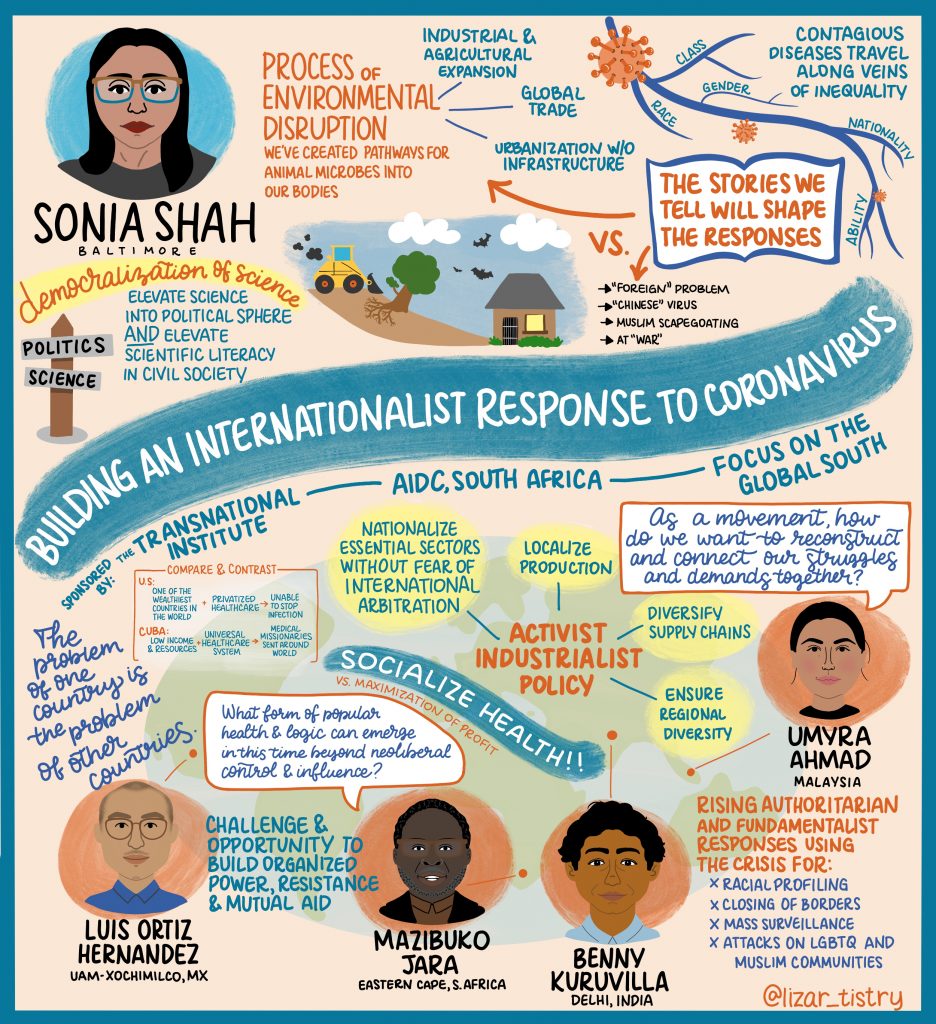

Chapter One – Building an internationalist response to Coronavirus

‘Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.’ Arundhati Roy

Unleashing fear and confusion among citizens and states across the world, COVID-19 demanded an internationalist response as it exposed social inequalities and the inadequacies of public health systems in developing and industrialised economies. The panel explored the global dimensions of the pandemic, discussed what resistance and solidarity can look like and the ways social movements may organise an internationalist response.

Analysis

According to Sonia Shah, author of Pandemic: Tracking contagions from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond, the pandemic was a ‘ticking time bomb’ which experts knew was coming. Humans have taken over half the surface of the planet and non-human species crowd the ever decreasing habitats left behind – frequently next to where we live and work in homes, towns, and farms. Industrial expansion at the expense of wildlife habitat is at the root of COVID-19’s spread, amplified in our cities and travelling throughout a global network created to rapidly trade commodities. Ebola originated in West Africa from a single event where a two year old child was playing near a tree in which bats were roosting – the child fell ill, infected family members, their healthcare workers and their family members and so on. This massive outbreak killed over ten thousand people.

There is a dynamic between disease and poverty that mirrors existing inequalities. Cures for malaria – ‘a disease of the poor’ – have been available for over a hundred years, yet hundreds of thousands of people every year still get sick and die from it. Shah understands that there is not ‘a lot of drug development for diseases that affect the poor’ – the best remedy for malaria is based on a 3000 year old Chinese medicine. Illness remains unaddressed even though there may be easy solutions – it is down to lack of political will.

Public health professor Dr Luis Ortiz Hernandez draws parallels between the United States and Cuba in their responses to the pandemic. The US health system based around private insurance is disorganised, struggles to contain the infection, and sees hospitals compete for ventilators. Meanwhile Cuba’s less resourced but universal health system organised around family physicians sees community workers identifying people with infections then isolating them, going as far as to send medical missions around the world because the country has internally controlled the epidemic.

Focus on the Global South’s Benny Kuruvilla describes the dual necessities of containing COVID-19’s spread while minimising the social and economic consequences on the vulnerable and marginalised. Before the crisis, India’s huge informal workforce had already experienced a precarious job market, cramped rental accommodation and no social security, following a long-standing agrarian crisis where tens of millions left rural areas to seek work in the cities. The economic fallout of Coronavirus saw migratory workers undertake a mass exodus from large business centres back to rural villages where jobs are scarce.

Mazibuko Jara of the South African Tshisimani Centre for Activist Education says that the crisis has shown his country’s elites to be ‘out of their depth’. South Africa is the most industrialised nation in African continent, yet millions of poor and working people are left with no food, water, or adequate medical facilities. Resources to fight the pandemic are out of the public’s hands, with the government introducing inadequate social and economic measures, leaving the private sector to dominate the emergency health response.

Umyra Ahmad of the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) in Malaysia states that the pandemic cannot be isolated from systemic faultlines – authoritarianism, fundamentalism, and neoliberalism are all entrenching themselves during this period of flux. Xenophobia is heightened as specific communities – Muslim and Chinese especially – are seen to be culpable for spreading the virus. Racial profiling has led to closing off borders, while mass surveillance and the misuse of personal data are being justified as the unfortunate by-products of ensuring public safety. The push for exceptional laws impacts most upon already vulnerable communities – law enforcement agencies are gifted executive powers, while misinformation and propaganda may be deployed as a tactic of social control. Global governance is not able to react to a situation like this, with bodies like the International Monetary Fund responding to the economic fallout with a ‘neoliberal’ approach, doing little for the most marginalised.

Solutions

Despite the devastation the virus has wrought across the globe, the panel believes that these politically uncertain times provide opportunities at an international level.

Sonia Shah discussed the unique way that everybody is focused on a single pathogen – even the world’s wealthy elites are getting sick, losing money and work. Telling a compelling story of the virus to the widest possible audience may offer the chance to address the root causes of its spread, insisting that all interventions consider the fundamental rights of humankind. At a time when people are ‘getting a crash course in epidemiology and public health’, science should be brought into the political sphere, and civil society can look to empower the public with scientific literacy.

Dr Luis Ortiz Hernandez feels this novel situation gives people time to consider not only what is best for their immediate families but also how society as a whole can take care of every citizen. Rather than simply disseminating data and guidelines around the virus and its spread, the World Health Organisation should spearhead a more active and coordinated response.

Benny Kuruvilla believes it is time for free trade treaties to be altered, and countries to instigate a more ‘activist industrial policy’. Medicines can be better developed domestically or at regional levels rather than extending a dependence on foreign imports – India, the second largest nation on earth relies on China, the biggest, for 70 per cent of its drugs. States should further be able to requisition private hospitals for public health reasons without the threat of litigation from lawyers acting on behalf of multinational healthcare conglomerates.

Mazibuko Jara thinks we can embed the notion of healthcare as a right and as a public good. There is hope in the practices of community-based health groups who provide ways of ‘socialising’ healthcare beyond existing public health systems. Alternative systems of public financing can be explored outside the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, while mutual aid networks and peasant mobilisations across the world can offer support to citizens if states fail in their duty of care.

Umyra Ahmad sees a heightened awareness in recent times of the international arena, giving social movements the space to break out from their silos and connect their struggles. In framing their demands, an alternative and transformative system can be imagined which, in the spirit of co-creation, highlights, amplifies and spreads new narratives from communities working on the ground.

Further resources: ‘Coronavirus: the need for a progressive internationalist response’, Transnational Institute

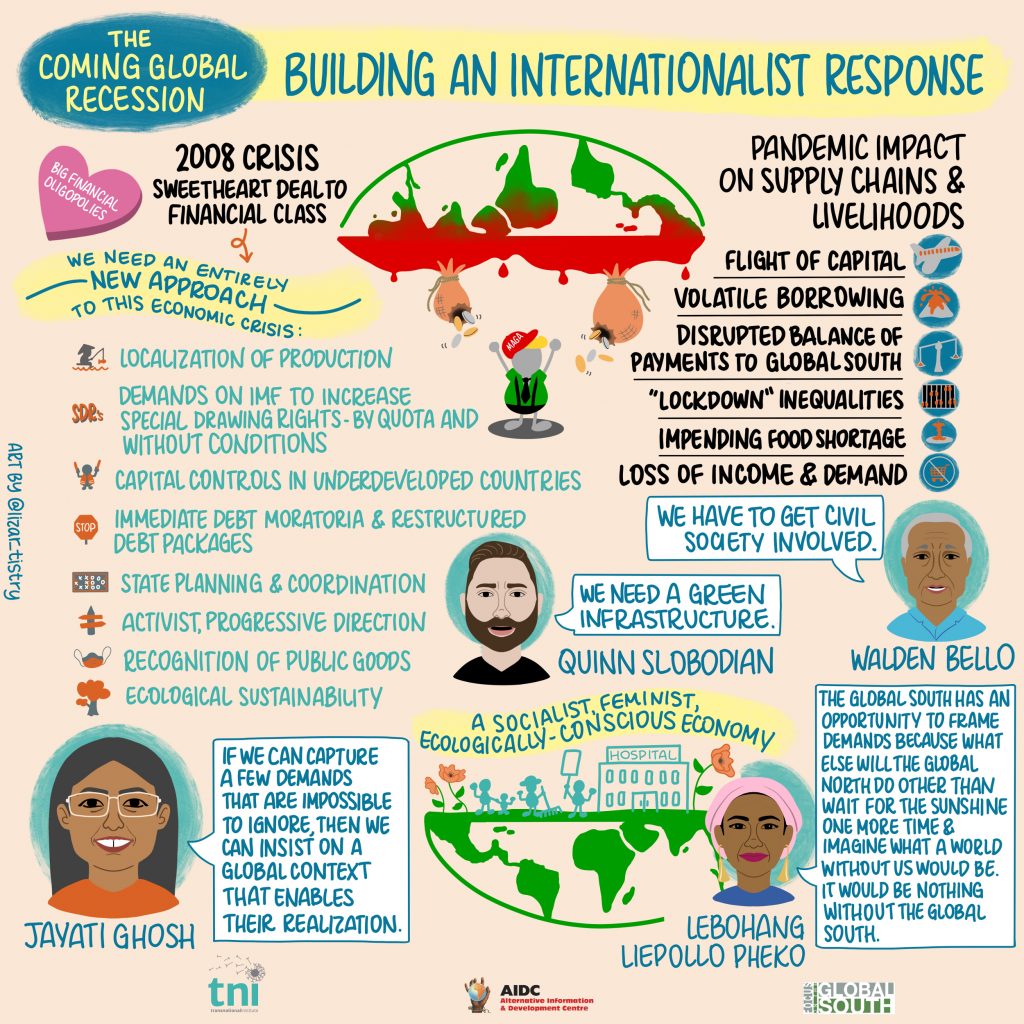

Chapter Two – The coming global recession

‘To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships’. W.E.B. Du Bois

The worldwide economic fallout from COVID-19 looks set to have greater impact than the virus itself, especially in the Global South. The panel discussed how social movements can advance cogent economic responses where they failed following the 2008 crash, and address the underlying structures of injustice.

Analysis

According to Economics Professor Jayati Ghosh we have reached an unprecedented moment. The economic impact of the pandemic will be devastating – worse than the 20th century’s two World Wars and the great crashes of 1929 and 2008. Simultaneously shutting down large parts of the global economy has significantly reduced incomes and supply, leading to a shortage of services and necessities, and exports collapsing in the travel, transport, and tourism industries. A cessation of economic activity has seen bond markets collapse in many emerging countries, currency depreciation, volatile borrowing, and capital flight. Inequalities have increased – both between and within countries – and developing countries are the worst hit.

The structures of power may not be ‘dramatically affected’, but as with all capitalist crises, it will impact upon workers and women the most. The outcomes of this crisis cannot be anticipated, though war is a possibility. Global institutions show little vision in bringing the international community together and the chances of cooperation are often undermined by ‘horrible’ leaderships in many countries, which fail to listen to or negotiate with civil society.

Walden Bello, TNI Associate and author of Paper Dragons: China and the Next Crash, believes we have entered the second big crisis in globalisation in just over a decade – many countries barely emerged out of the 2008 crash, and do not seem to have learnt its lessons. During the last downturn, governments of major economies focused their resources on protecting big financial oligopolies rather than saving jobs and homeowners – this time around, the most severe crisis in the capitalist system’s history, their focus could go the same way. States are usually ‘instruments of the elite, the ruling class’ and we have seen authoritarian measures deployed from India to the Philippines designed not only to deal with the public emergency, but also to strengthen executive control.

Quinn Slobodian, Author of Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism, thinks that the virus can be viewed in three distinct ways: as an X-ray, exposing the existing structures of our societies and economies; as a dress rehearsal, for when we will have to respond to upcoming collective recessions; and as a dynamo, exacerbating and exaggerating existing political tendencies. The authoritarian right is finally ‘learning about money’, with both the League in Italy and National Front in France favouring anti-austerity measures to deal with the crisis. In an ‘era of fantasy and fabulism’, progressives will find themselves needing to argue with the far right not only in economic terms, but also debunking their conspiracies, such as ideas that coronavirus was created in a Chinese laboratory or caused by 5G technology.

Lebohang Liepollo Pheko of the South African thinktank Trade Collective understands that neoliberalism’s fixation on ‘competitiveness’ has led to the ‘unnecessary’ catastrophe we find ourselves in. We are ‘not here by chance’ – instead the current crisis is part of an epochal moment dating back to the 1970s which launched an era of financialisation. The virus will be no great equaliser: across Africa currencies have been overvalued – from the South African rand to the Kenyan shilling – and are now depreciating compared to the US dollar.

Solutions

Though state authorities and large companies would like to see a rapid return to ‘business as usual’, the panel believes that social movements have the ability to change the narrative, putting forward progressive solutions to the current crisis.

Jayati Ghosh notes the need to make immediate demands that are ‘socialist, feminist and ecologically conscious’. These include pressuring the IMF to create global liquidity and a debt moratorium, encouraging developing countries to instigate capital controls and better localise employment, production and consumption, and ensure that public goods like health and care work are recognised and protected. Progressive forces are weak, but may be able to revive by ‘capturing people’s imagination’ and creating enough public support that governments might cede to their demands.

Walden Bello believes that crisis and conflict on the streets – with several groups defying lockdowns ‘imposed from above’ – present both problems and opportunities. Responses need to be progressive, not authoritarian, and our economic life must be radically reorganised to offer a different kind of politics and create a truly popular democracy.

Quinn Slobodian outlines ways to ensure that public responses to financial instability are better than those proposed after 2008. When people come back to work, ‘green infrastructure’ should be in place, with workplaces pushing a zero carbon model. Worker representation on boards can form part of any bailout, in addition to an immediate debt moratorium as Argentina has argued for, and a prohibition on bonuses. Similarly, at national level, economic recovery plans must be strictly tied to socially-just ecological transition. It is possible to ‘retool’ international institutions like the IMF and WHO given the vacuum of US involvement, as their mandates change over time. A return to localism can be promoted not only around issues of food security but also pandemic preparedness.. These initiatives have the benefit of encouraging solidarity, with people checking in on each other as part of wider local care networks. There is ‘inventiveness in resilience’, which can spark new forms of political action.

Lebohang Liepollo Pheko sights an opportunity to move away from neoliberalism, with countries in the Global South having witnessed that sovereign wealth funds ‘don’t solve everything’ and debt is bad (‘bad bad bad – morning. noon and night’). Developing countries are used to suffering, and the global nature of the pandemic may aid them when reframing their demands from larger economies. The role that state banks may play in a future economy should be considered, alongside the potential for wealth taxes and the introduction of a basic income. Gross Domestic Product as a measure of achievement is ‘bunk’, of little use, and could be replaced with the quality and comprehensiveness of a nation’s healthcare services to define its success.

Further resources: The Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Developing Countries, Inter Press Service

Chapter Three – A Recipe for Disaster: Globalised food systems, structural inequality and COVID-19

‘The world we want is a world in which many worlds fit.’ Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional

Global food systems and industrialised agriculture have been put in the spotlight due to their critical role in the spread of the pandemic. The panel discussed working towards minimising the power of international agribusiness, fighting for food sovereignty, securing better rights for small farmers, and making sure fewer people go hungry.

Analysis

‘Agriculture had a role to play in this crisis’, according to Rob Wallace, the author of Big Farms Make Big Flu. The transmission of COVID-19 follows the pattern of deadly viruses such as SARS, Ebola and Zika moving from non-human species into human populations, as shifts in land use, migration into recently urbanised areas, and the expansion of factory farms make new influenzas more likely.

Disease and deficits are interacting – for many impoverished people access to food is a more pressing concern than the virus itself, while in countries like Brazil and the US, migrant farm workers’ wages are lowered as ‘pandemic relief for agricultural companies’.

Moayyad Bsharat of the Palestinian Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC) argues that policies around privatisation have made healthcare unaffordable for many, meaning that small scale farmers and their families often lack the financial capacity to access healthcare. There is an urgent need for food producers to get back to their land and cultivate gardens to harvest healthy produce rather than rely on state handouts or the commercial and chemical processes of agribusiness.

Arie Kurniawaty of feminist organisation Solidaritas Perempuan (SP) in Indonesia feels that though her country is rich in agriculture and fisheries, government policies are ‘biased towards the middle class’. Indonesian authorities are more concerned with the needs of the military than allocating resources towards the public good. The current crisis falls hardest on women, who make up most of those working in the country’s traditional food trades. Women are finding it difficult to buy and sell produce at markets, which lacking the state support to implement health and safety protocols, are labelled unhygienic and forced to close.

Sai Sam Kham of Myanmar’s Metta Foundation argues that conflict, land grabs, dispossession and migration are all interlinked, with the country’s rural population struggling as the government fails in its attempts to provide citizens food. A backdrop of xenophobia against migrant workers returning from neighbouring countries and state control of the Internet in conflict-ridden areas has jeopardised many people’s access to the essential information needed to survive the emergency.

Paula Gioia, who works as a peasant farmer in Germany, believes that industrialised agriculture in recent decades has strengthened corporations, labour exploitation, and disease. Across Europe, the income of small food producers is being threatened by the closure of public markets, canteens and restaurants, with production concentrated on supplying the larger supermarkets. In Spain, France and Italy, a fallow period for tourism has seen many local food producers lose their biggest source of annual income, while seasonal agricultural workers find themselves urged to accept dangerous working environments and longer working hours. European farmers, with an average age of 65, are more vulnerable to the virus than much of the continent’s workforce and due to restrictions on movement face extra difficulties accessing their fields and delivering produce.

Solutions

The panel discussed how the public can help avert a food crisis and prevent an already exploited agricultural workforce falling victim to both the disease and the state response to it.

Rob Wallace argues for a profound shift in our relationship with the planet. Learning from indigenous groups, people can fight to reclaim rural and forest landscapes and waters, restart natural processes, and reintroduce crop diversity. The ‘story of food’ should be re-established – for it not to be seen as dependent on an industrial economy but a natural economy, using sun, soil and the life cycles of animals to feed and nourish the population.

Moayyad Bsharat’s Union of Agricultural Work Committees is distributing hundreds of thousands of seedlings to assist Palestinian farmers returning to the land, in addition to providing hygiene kits to their families. He calls for those providing local support to globalise the struggle against capitalism.

Arie Kurniawaty sees an opportunity to show international solidarity and prove there is no need for people to rely on agribusiness for food and livelihoods. Since the crisis hit, there have been several local initiatives aimed at bringing together the needs of rural and urban people. Food barns have been built anticipating future scarcity while the distribution of government aid packages is monitored in a bid to root out corruption.

Sai Sam Kham says civil society and public opinion in Myanmar demands an immediate end to conflict. While welcoming China’s offer to provide medical support to the state, the superpower’s strategic economic and political interests in the region is cause for concern.

Paula Gioia sees hope in smaller European farms feeding their local populations with fresh, healthy food, often in open air peasants’ markets at a fair price, alongside the growth of consumer cooperatives and shopping groups. The right to food and nutrition is paramount, and people should fight to guarantee public access to fields and waters. Public policy should focus on providing Common Agricultural Policy payments to small-scale farmers, delivering a safe environment for land workers, supporting new entrants into agriculture, and ensuring generational renewal.

Further resources: Public policies for food sovereignty, Transnational Institute

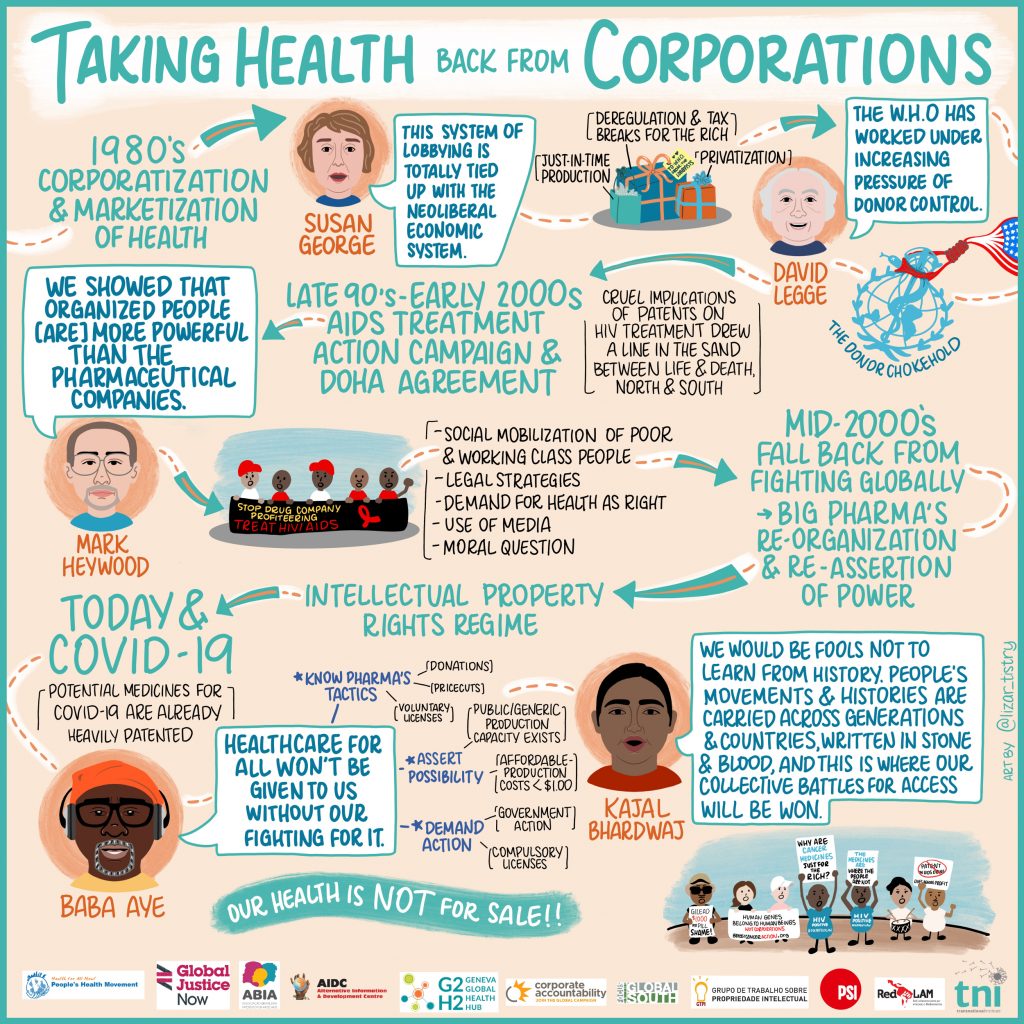

Chapter Four – Taking Health back from Corporations: pandemics, big pharma and privatised health

“We know now that Government by organised money is just as dangerous as Government by organised mob.” Franklin D. Roosevelt

For decades, corporate power has entrenched itself in healthcare delivery – public health providers are increasingly privatised and big pharma has profited while withholding access to life-saving medicines for those who cannot afford them. The panel discussed what needs to change in the global governance of health.

Analysis

According to President of the Transnational Institute Susan George, the world is ‘not ready for this pandemic because we allowed our health systems to become neoliberalised’. Globally, an underpaid, underequipped public health workforce sits beside chains of profit-making hospitals and private clinics.

The pharmaceutical industry – whose ten biggest companies are worth $1.8 trillion – continually lobbies Washington and Brussels to further push a deregulatory agenda that seeks profit-making over saving people’s lives. That there are no reserves of supplies to tackle health epidemics is by design, not by accident.

Baba Aye, Health Officer at Public Services International, tells us that a 1978 international conference organised by the World Health Organisation and Unicef was a flashpoint in the struggle towards universal healthcare. The United Nations agencies proclaimed a wish that by the year 2000 there would be health provision for all – however, corporations were able to subsequently argue that they could play a leading role in addressing the lack of money invested in public healthcare systems. From private finance initiatives in Britain and across Africa to the introduction of user fees, public money has frequently been used to subsidise private interests rather than provide universal coverage.

South Africa’s Daily Maverick editor Mark Heywood looks to his country’s struggle with big pharma in getting access to HIV/Aids medicines. Pharmaceutical companies took the post-apartheid government to court in order to stifle its attempts to make medication more affordable, citing World Trade Organisation rules around intellectual property rights. Successful campaigning pressured the WTO to establish the Doha Declaration in 2001 which allowed states to circumvent patent rights for better access to essential medicines. While HIV/Aids medication has become more accessible for those in developing countries, pharmaceutical companies are still able to patent treatments for many preventable illnesses and thus restrict access for the poorest people. Considering the current crisis, Heywood believes the world ‘cannot afford to wait for a vaccine to be developed to start raising questions about access, affordability, patents’.

Lawyer Kajal Bhardwaj understands that intellectual property rights, enforced by international trade rules, are deeply entrenched in national and regional legal systems, making swift action against the pandemic difficult without first guaranteeing corporate compliance. Myriad private patents have been recorded in the treatment of COVID-19 – its diagnosis and prevention as well as medicines and vaccines. Big pharma can block the manufacturing of affordable treatments by withholding access to patented products that may be repurposed – during the peak of the outbreak in Italy, those producing parts for ventilators through 3D printing were threatened with legal action by companies that owned the patents.

David Legge of the People’s Health Movement argues that the failure of research following prior pandemics and the World Health Organisation’s lack of skepticism regarding transmissibility contributed to delays in travel restrictions resulting in the rapid spread of COVID-19. The WHO is dependent on funding from rich countries, the World Bank and big philanthropic donors.. The American government has pressured the secretariat over recent decades to advance the interests of large private companies, using the threat of defunding to assert its control and push trade liberalisation. Proposals for publicly funding the research and development of pharmaceuticals to allow lower costs are widely supported by the member-led World Health Assembly but have not been enacted by the WHO.

Solutions

The pandemic has shown the necessity of working towards universal public health systems and increasing access to medicines so that everyone in need can afford them.

Susan George believes that ‘it is possible to have everyone cared for’ – if corporations are taxed properly, our social security systems are improved and the health lobby’s attempts at influencing legislation are scrutinised and fought.

Baba Aye wants populations to loudly proclaim that ‘our health is not for sale’. A new global consensus has developed that healthcare is a right – an idea already present in most countries’ constitutions. Swift action by both governments and social movements has already led to a number of private hospitals requisitioned to deal with the pandemic, and factories converted to manufacture personal protective equipment and medical supplies to make up for a shortfall.

Mark Heywood understands that ‘sometimes it takes a crisis to make people work together’. It is through public investment in research that medical breakthroughs are achieved, and people should demand universal access not only to a coronavirus vaccine but to the knowledge and understanding behind it. Activists should remember that big pharma is not invincible – organised people are much more powerful. Movements in Africa and India in the past have forced down prices of medicines, saving millions of lives.

Kajal Bhardwaj thinks that the threat of government action encourages good behaviour from pharmaceutical companies. There have been positive developments in Germany, Canada, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador where authorities have implemented measures to issue compulsory licenses. There is also capacity in many countries to ramp up production of generic medicine at extremely affordable prices.

David Legge hopes that with enough public pressure, it is possible to successfully campaign for intellectual property reforms. Efforts should be focused on lobbying authorities to ensure – in the face of hostility from big pharma – compulsory licensing and allow generic drugs to be produced without the consent of the patent owner.

Further resources: People’s Health Movement, Coronavirus – statements and responses

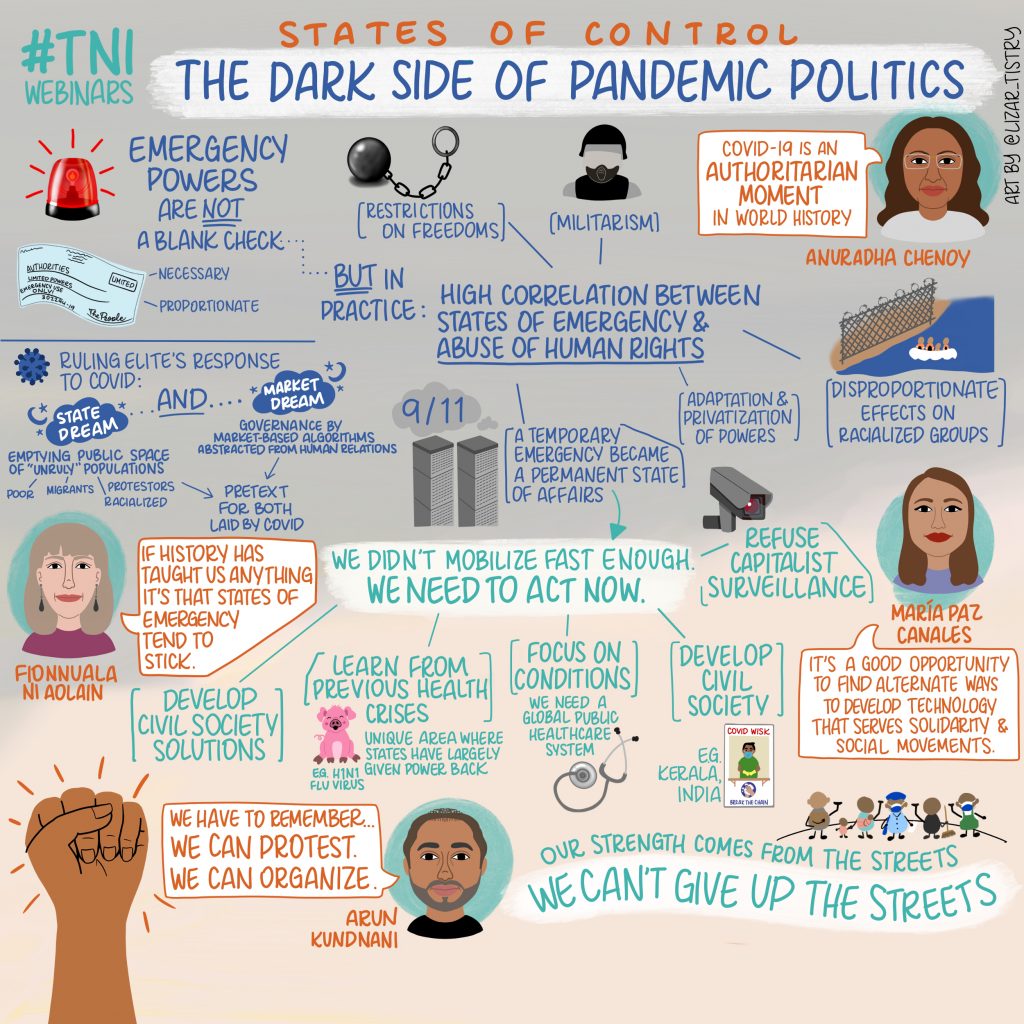

Chapter Five – States of Control: The dark side of pandemic politics

“We are connected to one another, in the deepest sense, through our common pain. When we lose that connection we lose our humanity.” A Sivanandan

During political crises, states push for emergency powers. Following the attacks on the World Trade Centre on September 11th 2001, for example, a wave of immediate measures was introduced to counter a terrorist threat, yet much of this architecture remains in place to the present day. The panel reflected on a wide range of issues from authoritarianism and surveillance to the rise in anti-migrant sentiment and Islamophobia, and agreed that the rights of citizens are being curtailed across the globe and must be resisted.

Analysis

According to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights while Countering Terrorism Fionnuala Ni Aolain, parallel to the medical pandemic, ‘we are seeing an epidemic of emergencies’. Under international law, emergency measures can be introduced to protect public safety, health, and national security, yet there is a ‘pattern of non-notification’ where states choose to use these powers but fail to inform official bodies or their own citizens. During emergencies, the political culture of nations often changes – oversight mechanisms are removed in favour of increased powers for the executive, police and security forces.

Alongside parliamentary opposition, civil society can find it difficult to know what states are doing as emergency legislation refrains from naming itself, with measures often tucked into health and sanitation bills. Citizens in a state of fear may be willing to sacrifice their liberty, believing that during an emergency human rights are not a priority, yet temporary powers have the tendency to stick around.

Author of The Muslims are Coming! Islamophobia, extremism, and the domestic War on Terror Arun Kundnani points to 9/11 as a useful reference point for those monitoring authorities’ emergency measures. The attacks on the World Trade Centre saw a temporary emergency transform into a permanent state of affairs. Almost 20 years later, acts of terrorism still take place across the world, the detention camp at Guantanemo Bay remains open, and the wave of anti-Muslim racism enveloping Western nations has further ‘globalised’ into countries such as India, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar. Authorities now look to empty states of their unruly populations while the influence of big business sees our lives determined by market-based digital algorithms. New licenses given to police forces to implement quarantines and lockdowns has only intensified existing forms of violence. The COVID-19 crisis has given rise to a clampdown on migrants – already existing anti-migrant sentiment has intensified, while those in immigration detention centres experience high infection rates with little possibility of isolation. Various EU countries continue to turn away refugees in the Mediterranean, in Qatar migrant workers offered coronavirus testing were rounded up then deported, and from Hungary to the US, nativist leaders have weaponised the pandemic, unleashing new forms of racism.

Author of Militarisation and Women in South Asia, Anuradha Chenoy says that the current crisis ‘can be marked as an authoritarian moment in world history across countries’ where regimes look to expand control over citizens and centralise power even within democratic systems. When the virus began to spread, almost all states – unprepared and panicked – similarly reacted, taking emergency measures without declaring emergencies. The military were put on the streets in Israel, Philippines, Yemen, and Iraq, and self-appointed vigilantes linked to right wing populist governments took on the role of monitoring particular marginal communities. The stigmatisation of outsiders and dissenters has seen police use chemical disinfectant on migrant labourers and investigative journalists picked up and incarcerated. Global bodies such as the World Health Organisation are being undermined by the leadership of member states – the US has sought to remove itself fromWHO’s jurisdiction – while supranational organisations like the EU and ASEAN seem more concerned about closing borders than international solidarity.

María Paz Canales of the digital rights campaign Derechos Digitales believes there has been a ‘repurposing of many surveillance technologies in the context of the pandemic’. Private firms are offering their services to the state under the auspices of being helpful in a moment of crisis, yet are hoping to whitewash technologies through their new use. Many were ineffective when deployed for their original purposes and are inefficient in tackling the spread of the virus as the type of data recorded is not precise enough. Facial recognition technologies – used in the past in the name of public safety and national security – in particular have very limited use. The danger is that ‘we are not surveilling the virus, we are surveilling people’, impacting upon the rights of vulnerable groups and stigmatising the sick.

Solutions

The panel talked about how to protect fundamental rights in the shadow of creeping authoritarianism, outlining ways of mobilising ourselves during lockdown, and imagining lives less dependent on technologies.

Fionnuala Ni Aolain considers the global effect of the pandemic – every single person’s rights are being impinged upon in certain ways and some more than others. The language of rights for all can be reclaimed, and the idea of health as a basic human necessity entrenched – after all, governments ‘shut down the world’ on the basis of the protection of the right to health. Though the pandemic may have empowered authoritarians, weakened democracies and multilateral systems, producing a ‘narrower and tightly squeezed civil society space’, Ni Aolain argues that ‘crisis is innovation’ providing an extraordinary opportunity to emerge with a healthier democracy.

Arun Kundnani warns people to be wary of corporations trying to exploit the current situation to create their own version of a new order. The increasing digitalisation of our social lives must be fought as the public becomes dependent on big tech to provide and mediate these relationships – over lockdown, the use of video chat has become the norm in accessing healthcare and higher education, and tech companies want to keep this in place as populations move out of an emergency situation. Activists ‘cannot give up the streets’, and should fight to reclaim public spaces and defend a ‘sense of human connection’. It may well be safer to attend protests than turn up to workplaces. Quoting journalist Susie Day, Kundnani predicts ‘The revolution will not be quarantined’.

Anuradha Chenoy notes that there has been no end to defence spending – citizens should be asking ‘where is the defence against this virus?’, and demand a transfer of military expenditure towards health expenditure. Though the compact between civil society and the state has been breaking down over recent years, the public has been able to show its strength during the crisis, delivering mutual aid and food parcels to communities in need. Instead of globalisation, Chenoy argues, there should be international solidarity – its symbols including alternative media outlets have been emerging in the face of a toxic press.

María Paz Canales says people would be wise to reject the ‘technosolutionism’ of not only authoritarian but, increasingly, democratic governments. Citizens need to be more critical about which type of data is useful for their purposes, and seek to develop alternative technology that opposes ‘capitalist-surveillance logic’. Some data can prove helpful in fighting the pandemic, related to a country’s testing capacity, resource allocation, and directing assistance to the most vulnerable, yet there is no need to capture the identity of individuals, putting certain people at risk of discrimination in terms of immigration and employment status.

Further resources: From Fanon to Ventilators; Fighting for our right to breathe, Arun Kundnani, ROAR

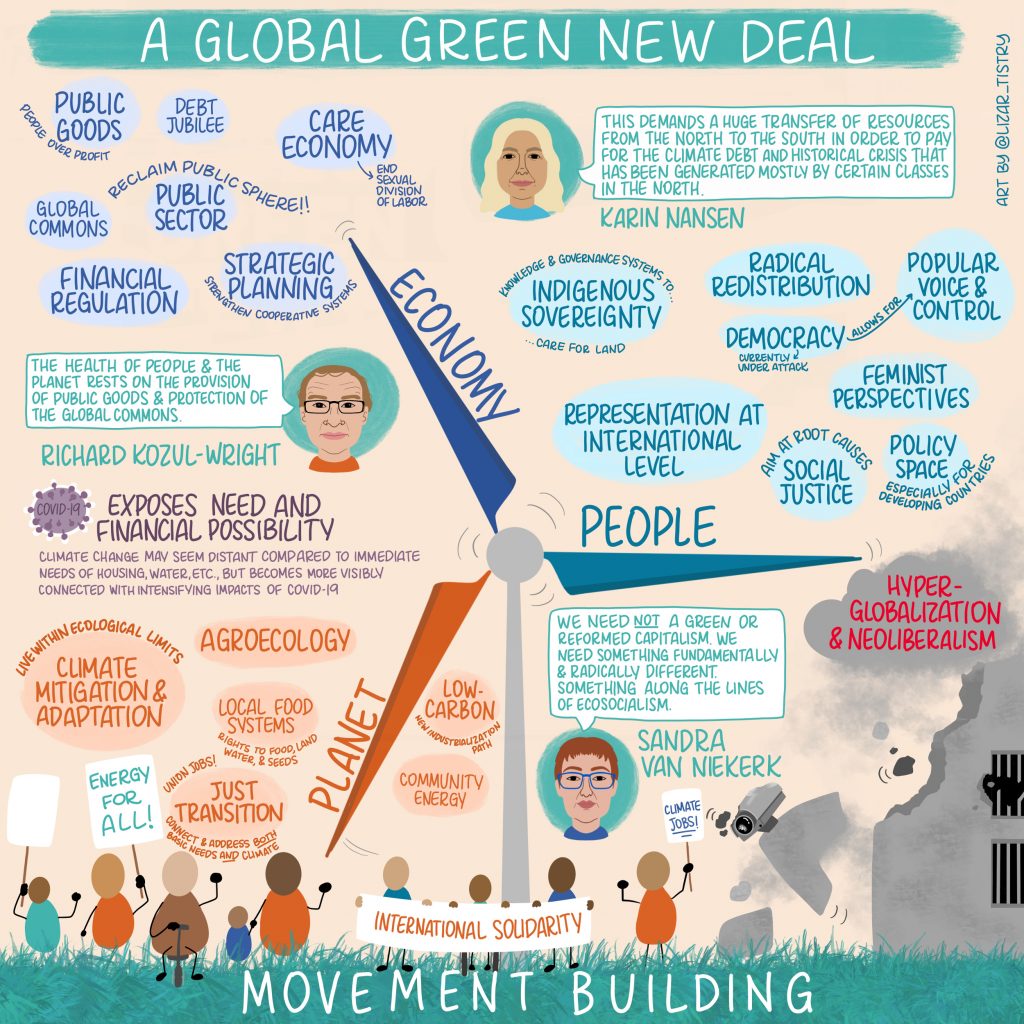

Chapter Six – A Global Green New Deal

“We have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish for ever.” Bertrand Russell

A more serious emergency than COVID-19 is on the horizon – the climate emergency. Decisions forced by the pandemic to shut down extractive global modes of production saw not only a reduction in carbon emissions and air pollution, but demonstrated states’ potential to take bold decisions to protect their citizens. The panel outlined the challenges and opportunities of working towards a just transition to a sustainable world.

Analysis

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s Richard Kozul-Wright, comparisons can be drawn between the Green New Deal and the original New Deal. Both wish to contest economic power, regulate Wall Street, and invest in public services and infrastructure. Before Coronavirus hit, economic prospects globally were deteriorating following a period of hyperglobalisation, with Bretton Woods institutions serving as handmaidens of speculative, predatory forms of capital.

The response to the 2008 crash can be viewed as a ‘dry run’ for current and future crises – instead of going back to business as usual, COVID-19 has forced governments to tear up the neoliberal rulebook. ‘Tory chancellors suddenly discover their inner Keynesian selves’, with emergent ‘magic money forests’ concocting trillions of dollars to deal with consequences of the pandemic.

Chair of Friends of the Earth International Karin Nansen believes that humanity is at an impasse – related to the imposition of neoliberal logic which fails to work for people and the environment, endangers lives, and threatens public wellbeing. Companies are gaining more and more power and there is a widespread expansion of extractive activities, especially in the energy sector. Capitalism provides false solutions – carbon offsetting, for example, that is not a ‘real’ solution to addressing climate change. Those who generated the environmental breakdown comprise a small portion of the population in a few countries – those who are most affected barely contributed to it.

Sandra van Niekerk of the One Million Climate Jobs campaign in South Africa feels that the term ‘Green New Deal’ is contested having been hijacked by big capital, offering the veneer of environmental friendliness. Instead of encouraging a ‘reformed, green capitalism’, there is an urgent need to deal with the dual crises of unemployment and climate change. In South Africa – ‘one of the most unequal countries in the world’ – it is difficult to tackle climate change when you have no house or electricity, while renewable energy initiatives are hampered by trade regulations, limiting their ability to grow.

Solutions

The panel put forward a programme of action to encourage the just transition towards a green future that centres environmental justice and the needs of the most vulnerable people on the planet.

Richard Kozul-Wright believes the Green New Deal provides a ‘unifying narrative’ and calls for any new proposals, like the first New Deal, to be based around ‘an avowedly political project’ and embrace popular voices. Rejecting the concept of ‘degrowth’ as unhelpful framing particularly for the Global South, he advocates reforming the international financial systems in order to ‘reconnect a healthy people and planet with a healthy economy’. Bailout packages should reject austerity, introducing measures that are wage-led and job rich. This involves a massive investment push into climate mitigation and adaptation, reliant on progressive taxation, financial regulation, and strategic planning in industrial policy, with a far greater role considered for public banking. Though many reforms are rooted within nation states, work can be undertaken internationally with major economies helping to pull up the Global South.

Karin Nansen argues that the radical transformation of society demands public participation and democracy. Organising around a ‘common agenda’, the world may be able to transition away from fuel dependent economies, change energy systems and ownership, and move towards community-controlled energy production. In addition, there needs to be a huge transfer of resources from North to South to pay for climate debt and historic economic crises generated by former colonial powers. Nansen considers the example of Latin America, where peasant and indigenous movements have often taken a stand alongside women’s groups and trade unions as a critical model for the movements that need to be built to deliver this systemic change..

Sandra van Niekerk understands the need for a ‘radical restructuring of the economy’ and the redistribution of resources in a ‘hugely unequal world’. The public sector can employ people in new climate jobs; transport, local government, schools, hospitals, and housing could be made more energy efficient; and workers could be supported to transition away from the fossil fuel industry. Considering South Africa, where many people lack electricity, van Niekerk suggests not talking in terms of cutting back on the amount of energy generated – if there is a shortfall, many people may never have access to electricity, and continue to live in poverty-riven environments.

Further resources: Just Transition: How environmental justice organisations and trade unions are coming together for social and environmental transformation (TNI, 2020)

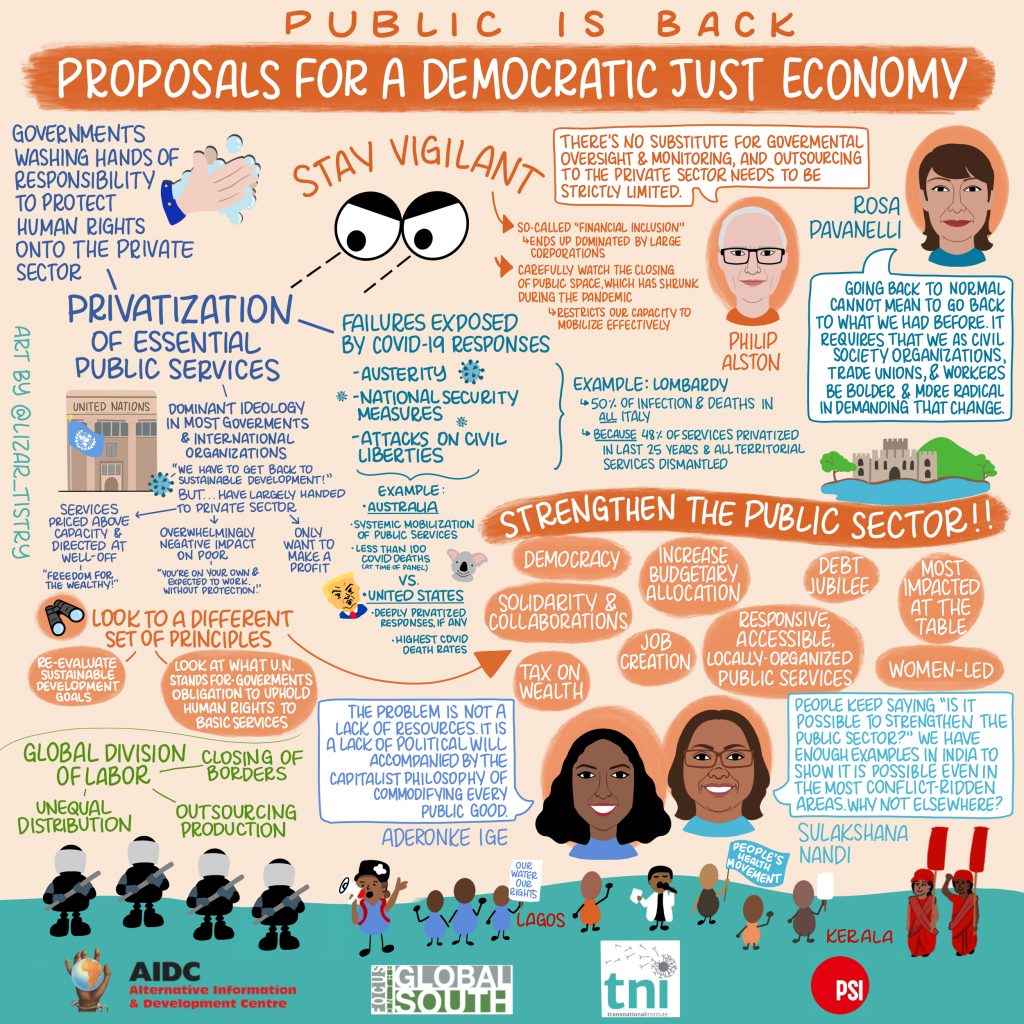

Chapter Seven – Public is Back: Proposals for a democratic just economy

“The little crash of 2008 was a reminder that unregulated capitalism is its own worst enemy: sooner or later it must fall prey to its own excesses and turn again to the state for rescue.” Tony Judt

There has been a groundswell of vocal support for public services during the current health emergency. The panel discussed the broad impacts of privatisation on countries’ wellbeing and people’s dependence on poorly paid frontline workers delivering essential services.

Analysis

According to former UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights Philip Alston, the steady privatisation of essential public services demonstrates that governments have been ‘washing their hands of human rights obligations’ by passing over relevant sectors to private interests. Across the world, access to even minimum services – from water, electricity, and transport to education, criminal justice, and welfare – is denied to many. If a country is unable to provide public services like a nationwide health system to its citizens, it is unable to deal with the pandemic, effectively throwing the bottom half of the population ‘under the bus’. The dramatic ideological shift from public to private can be traced back to Augusto Pinochet’s Chile in the 1970s and subsequent Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan’s administrations.

Despite very little supportive evidence, the assumption that private is always best– cheaper, more efficient, less corrupt, and ultimately better for societies – has subsequently become the dominant mentality of most governments and international organisations. In the push towards digitisation of the public sector, further steps may be taken in the privatisation of essential services – in recent years tech companies have been offering to assist the UK’s National Health Service deliver its commitments.

General Secretary of the global union federation Public Services International (PSI) Rosa Pavanelli believes that the pandemic highlights the failure of the neoliberal system, unearthing a deeply unequal global division of labour. National health services which have been the most privatised, such as the US, also have the most unequal societies, while many major economies outsource to developing countries because it is cheaper to employ their workers. Multinational corporations are able to avoid tax contributions, while countries in the Global South struggle to pay their debts to former colonisers.

Sulakshana Nandi of the People’s Health Movement Global in India believes that we have witnessed decades of privatisation under the guise of improving efficiency. The Indian government actively promotes vested interests, handing over district hospitals to the private sector, while reducing the national health budget, and rolling out a costly insurance scheme. Vulnerable groups entitled to coverage under the scheme are often not able to utilise it and rural areas remain under-resourced as the private sector routinely refuses to operate in remote regions, meaning they are ‘completely missing in action’ in the testing, surveillance, and treatment of COVID-19.

Aderonke Ige of the Our Water, Our Rights Campaign in Lagos, Nigeria, states that ‘you cannot leave the public good in private hands’, arguing that the ‘problem isn’t lack of resources, it is lack of political will’. The pandemic exposes the gap in the system, where governance is accompanied by the capitalist philosophy of commodifying every public good, including water. Nigeria has significant economic income, but still cannot prioritise universal access to water – women and young girls carry the greatest burdens, but are rarely consulted in public decision-making.

Solutions

The panel outlined ways to make the public sector more democratic and participatory, and how citizens can move away from subsidising large corporations in the delivery of essential services.

Philip Alston declares there are very few examples of private companies acting in the broader public interest, so ‘we shouldn’t expect it and it’s not going to happen’. Corporate actors will see no opportunity to profit from helping poor people, and services will always be priced above their capacity to pay and directed to those better off. Civil society can look at a different set of principles and institutions for delivering services. On an international level, people should reevaluate whether the sustainable development goals can be achieved, and more broadly determine what the United Nations stands for.

Rosa Pavanelli suggests the World Health Organisation’s commitment to researching and producing a COVID-19 vaccine which will be free to all is ‘invaluable’ for the ‘common good of humanity’. However, governments must be pressured to transform the direction of their economies. They must introduce an immediate wealth tax on digital corporations like Amazon and Google, that are profiting during this crisis. People can better interrogate how the closure of borders will affect food distribution and work towards more sustainable farming and energy production.

Sulakshana Nandi notes that in India areas with good food security programmes have often effectively dealt with the crisis, and more progressives states such as Kerala in the south have better health outcomes. The most vulnerable should be offered opportunities to have a say in decision-making and public sector workers need to be adequately resourced.

Aderonke Ige says that improved investment in the public sector amounts to ‘collective development’. The Our Water, Our Rights Campaign is a ‘child of necessity’, prioritising the rights and welfare of everyday users of water. The coalition, born in 2014, brings together civil society, the labour movement, youth and grassroots organisations. Women play an active role and have achieved a number of victories protecting Lagos’s water – authorities have tried to privatise access but are yet to succeed.

Further resources: The Future is Public, Transnational Institute (2020)

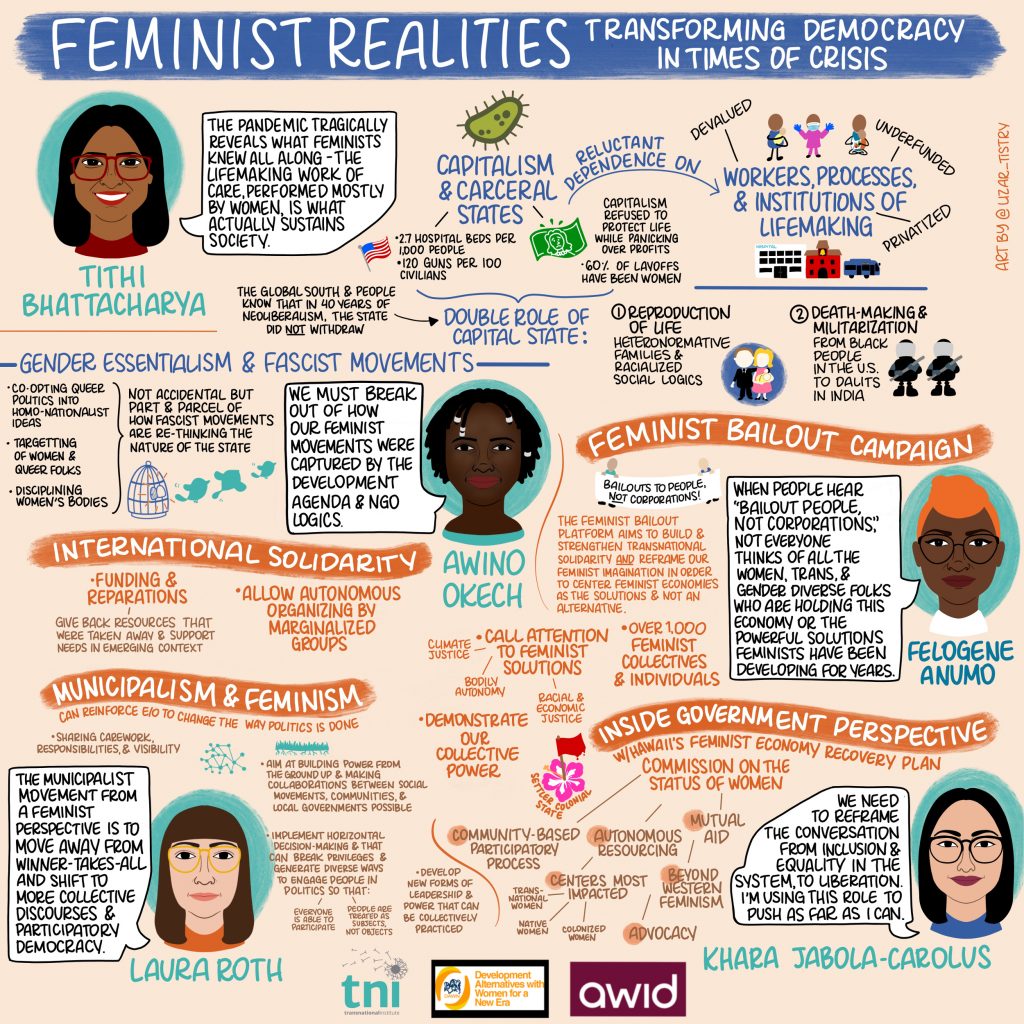

Chapter Eight – Feminist Realities: Transforming democracy in times of crisis

‘The function of freedom is to free somebody else.’ Toni Morrison

Patriarchal states have shown themselves incapable of facing global problems. The panel reflected on the condition of women across the globe, how to dismantle gendered labour hierarchies, and how to construct stronger, feminist participatory democracies.

Analysis

According to Tithi Bhattacharya, co-author of the manifesto Feminism for the 99%, the ‘work of women and gender non-conformist people makes all other work possible’. Though capitalism prioritises profit-making over life, it also depends on the processes and institutions of life-making, yet is reluctant to spend any money on this. Thus care work is devalued, underpaid or unpaid and there is a continual push to underfund or privatise schools, hospitals and public transport.

Professions that embody the spirit of care work – teaching, cleaning, nursing, homecare, food production – are undertaken in the most part by women, and it is they who are hardest hit by the current crisis: from those forced to work in unsafe conditions and risk being laid off, to others compelled to remain indoors with abusive partners as rates of domestic violence rise.

Awino Okech at the Centre for Gender Studies of the UK’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) believes that with governments failing to respond to public needs, democracy no longer works for the vast majority and our agency as citizens has been taken away. Renegotiating the social contract through electoral means has never looked less appealing to the public: authoritarian leaders and parties in the US, Europe and Latin America find themselves represented in national parliaments, while in Africa – from Sudan and Burkina Faso to Tunisia and Egypt – citizens may have ousted their leaders but have yet to secure the change they fought for. Ultra-nationalists, informed by their conservative and binary ideas around gender and sexuality, are targeting and disciplining female human rights defenders and the LGBT community, while feminist and queer politics is narrowly and opportunistically co-opted by certain governments in order to prevent wider, more important discussions about women’s and gay liberation.

Khara Jabola-Carolus, author of Hawaii’s Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for COVID-19, outlines some ways in which women can work positively within official structures. Most US states have a commission on the status of women – a tool left by 1960s feminists to help advance the movement – and Hawaii has one of the longest standing ones. This has the potential to provide a link between feminist activists and government, facilitating community-based participation by diverse women spanning race, class, age and life experience. Having an understanding of the shared trauma of colonialism and land loss in Hawaii, the commission seeks to reorientate the economy away from destructive industries – for example tourism and militarism – and to scale up the social safety net.

Laura Roth, co-author of the report Feminise Politics Now!, argues that pandemic responses show a trend towards top-down centralisation. In times of crisis, fear can make people worry less about who is making decisions, but Roth believes that feminism and municipalism, with their focus on building power from the bottom up, may offer an alternative. They are ‘great allies’: both change the way ‘politics is done’ and can link up social movements with local government, a lifeline for many people in sustaining relationships, taking care of the vulnerable, and looking after the invisible. Politics is something that ‘everyone should be able to do’ and citizens platforms have shown they can win elections at a local level – in Spain, these took power across some of its largest cities in 2015 on the back of a nationwide anti-austerity movement.

Solutions

The panel discussed ways of creating transformative feminist realities, revaluing women’s role in public life, and alternative non-patriarchal modes of power.

Tithi Bhattacharya believes that humanity should work towards a world where ‘life and life-making’ become the basis of social organisation – states must now be pressured to prioritise life over profit. The pandemic has normalised the view that nurses and farmworkers, not stockbrokers and CEOs, are ‘essential workers’. Women’s unpaid labour in the home amounts to ten trillion dollars globally – capitalism for hundreds of years has undervalued the lives of women, migrants and other marginalised people, yet networks of support, solidarity and survival have survived..

Awino Okech understands that ‘we are not all in this together’. It is therefore imperative that effective allyship is sought across borders, moving resources from the Global North to the South. The autonomous organising of marginalised groups should be respected, and transnational solidarity can occur without sharing the same physical spaces – though civil society should refrain from relying on those with access to funds from determining the success of initiatives in poorer parts of the world.

Khara Jabola-Carolus understands the need to move from the language of inclusion and equality to liberation. Her group uses shareable documents to co-create agendas and provide training to hundreds of government workers – telling stories that instil empathy and helping people better understand the lives of women and non-binary people.

Laura Roth hopes feminists will look towards municipalism to find ways of building new forms of power. Little will be achieved simply by bringing more women into politics or focusing solely on local issues – there is a need to innovate around new forms of leadership, share responsibilities and ultimately treat people as ‘subjects’ not ‘objects’ of politics. Participatory democracy can shoulder a collective spirit – women have the ability to break historic privileges, move away from confrontational discourse and bring care into the political arena.

Further resources: Feminists, it’s time to decide where public resources go (May 2020), AWID

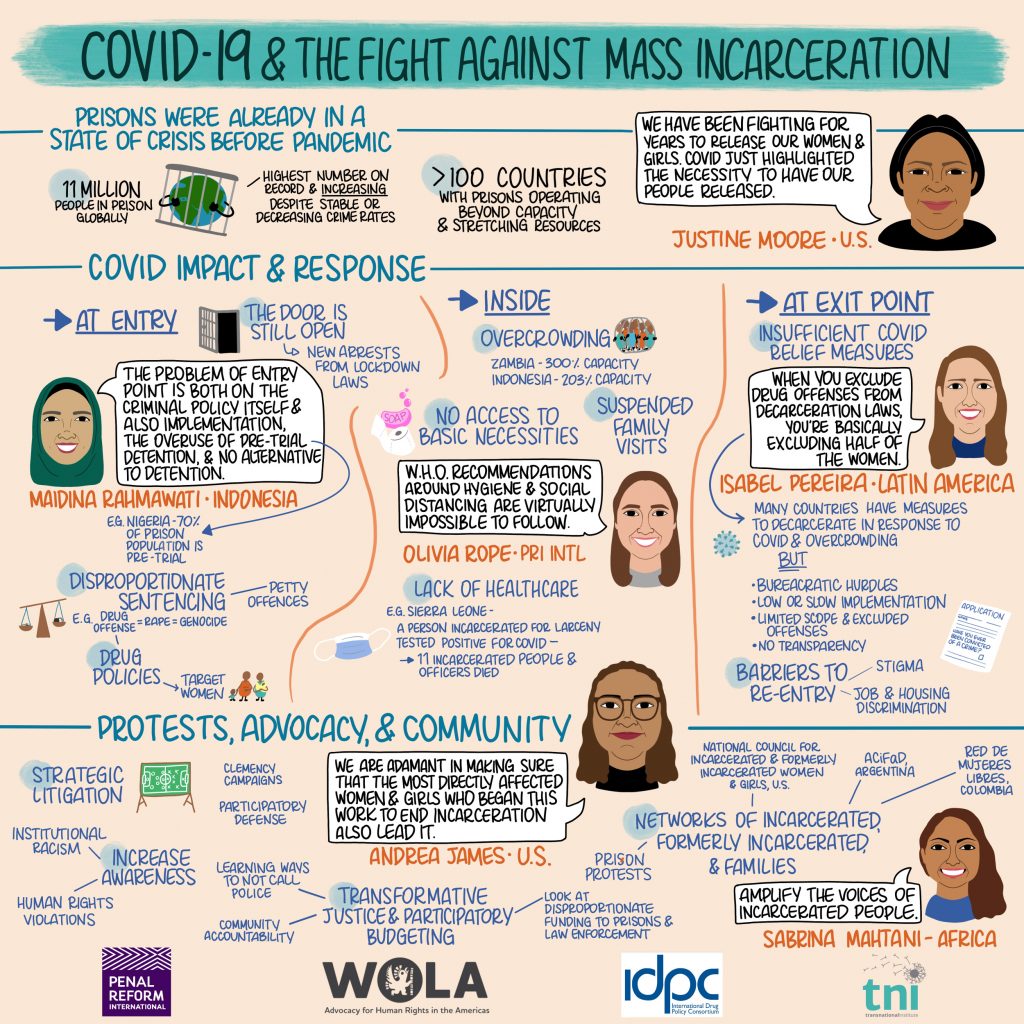

Chapter Nine – COVID-19 and the global fight against mass incarceration

“It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.” Nelson Mandela

COVID-19 has exposed a crisis in penal systems across the globe – prisoners live in unsafe conditions, lack legal support, and punitive drug policies drive up the numbers. With unprecedented numbers of inmates released to prevent deadly outbreaks in jails and detention centres, the panel discussed the societal costs of mass incarceration, the potential for criminal justice reform across the globe, and alternatives to imprisonment.

Analysis

According to Olivia Rope of Penal Reform International, prison systems were at breaking point before the pandemic, with 11 million people incarcerated globally – the highest figure yet, with numbers still on the rise. People are in no way becoming ‘more criminal’ – crime rates across the world are either stable or going down. Yet over 100 countries still operate above their maximum occupancy rate as imprisonment is increasingly used for those committing non-violent offences.

Within a system where mortality levels are 50 per cent higher than in wider society, there is an overwhelming lack of healthcare provision – the prison population is virtually unable to follow World Health Organisation guidance around Coronavirus and tens of thousands of people have contracted the disease inside.

Isabel Pereira of Dejusticia states that in Latin America prison overcrowding is rife and there is an excessive use of pre-trial detention. Societal discrimination leads police authorities to target women and the LGBT community. There has been an increase in the use of incarceration as a deterrent for minor drugs offenses, overwhelmingly affecting people from low socio-economic backgrounds – in some cases drug possession is placed on a par with the length of sentencing for rape and genocide convictions.

Andrea James and Justine ‘Taz’ Moore of the National Council For Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls in the USA argue ‘prisons are not financially equipped to take care of us’, and during a health crisis become a ‘death-trap’. Incarcerated people live in cramped sleeping conditions, and lack toilet paper, hand sanitiser, soap, masks and adequate food supplies, often reliant on those outside to provide these essentials. Disproportionate levels of criminal justice funding are put towards building new jails and providing police equipment rather than rehabilitating people in their communities on release. Women are often threatened with eviction by taking in people with convictions, and former inmates find it difficult to get work, making recidivism more likely because there are no resources to support them.

Advocaid’s Sabrina Mahtani believes that African states have reacted to the COVID-19 crisis by taking a law enforcement rather than public health approach. Prisons in Africa are old and overcrowded, lacking running water and soap which makes it difficult to maintain good hygiene. Women’s needs are often ignored by the authorities and if outside after curfew they risk being detained. The prison system lacks facilities for women, some of whom are imprisoned with their young children – access to basic supplies is problematic and there is one doctor for every 2000 detainees.

Maidina Rahmawati of the Indonesian Institute of Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR) believes that state authorities were not prepared for this outbreak. Prison overcrowding has become ‘undeniable’ during COVID-19 in a country which sees few alternatives to detention. Indonesia has an ineffective bail system that lacks transparency and under-resourced parole, probation and integration programmes.

Solutions

The panel discussed the urgent necessity for civil society to make the case for decarceration and effective strategies towards long-term structural reform of the criminal justice system.

Olivia Rope understands the pressing need to reduce numbers in prison and explore non-custodial alternatives to imprisonment, especially for women. Swift coordinated action by the Irish government, for example, saw the female prison population reduced by over one third at the start of the pandemic. Civil society needs to gather evidence to urgently highlight the plight of incarcerated women, while arguing for prisons, as part of society, to be better integrated into public health systems where inmates can access medicines, care and support.

Isabel Pereira sees networks of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and their families active in protesting poor conditions in prison. Budgets should be reallocated away from building new prisons and minor drug offences must not lead to incarceration.

Andrea James and Justine ‘Taz’ Moore urge people to ‘stay in touch with those inside’ and support the growing demands not just for reforms but rather abolition of prisons – an end to incarceration. Those who have experienced incarceration may be able to provide solutions – not just around reimagining the prison system, but reimagining whole communities. In recent years, a clemency project to commute the sentences of women who are elderly, pregnant, survivors of domestic violence, or terminally ill, has achieved success, and in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, campaigns to defund police departments are gaining traction. Women of colour are the fastest growing demographic in American prisons, and ‘defunding racism involves ending the incarceration of women and girls.’ In addition to being ‘vigilant on the fiscal side’ – monitoring the levels of investment set aside for new jails and police equipment – James and Moore advocate for more ‘transformative’ forms of justice, where neighbourhoods can come together to deescalate a situation without resorting to police involvement.

Sabrina Mahtani has witnessed civil society groups across Africa push for decarceration and provide urgent supplies for those incarcerated during the current crisis – adapting their capabilities to offer legal advice and monitor police activity. In Ethiopia, Senegal, and Kenya, thousands of detainees have been released in a bid to reduce overcrowding. Exploring alternatives to prison for drug possession, there is a push towards decriminalisation of petty offences which affect the poorest in society – ‘poverty should not be a crime’, Mahtani proclaims.

Maidina Rahmawati believes that the Indonesian government is aware of the ‘undeniable’ problems with its penal system, and has taken steps to release vulnerable inmates. The promotion of ‘restorative justice’ can help further reduce prison overcrowding across the country.

Further resources: The law of the land: decolonising criminal justice (March 2020) Oliver Durose at Verso blog

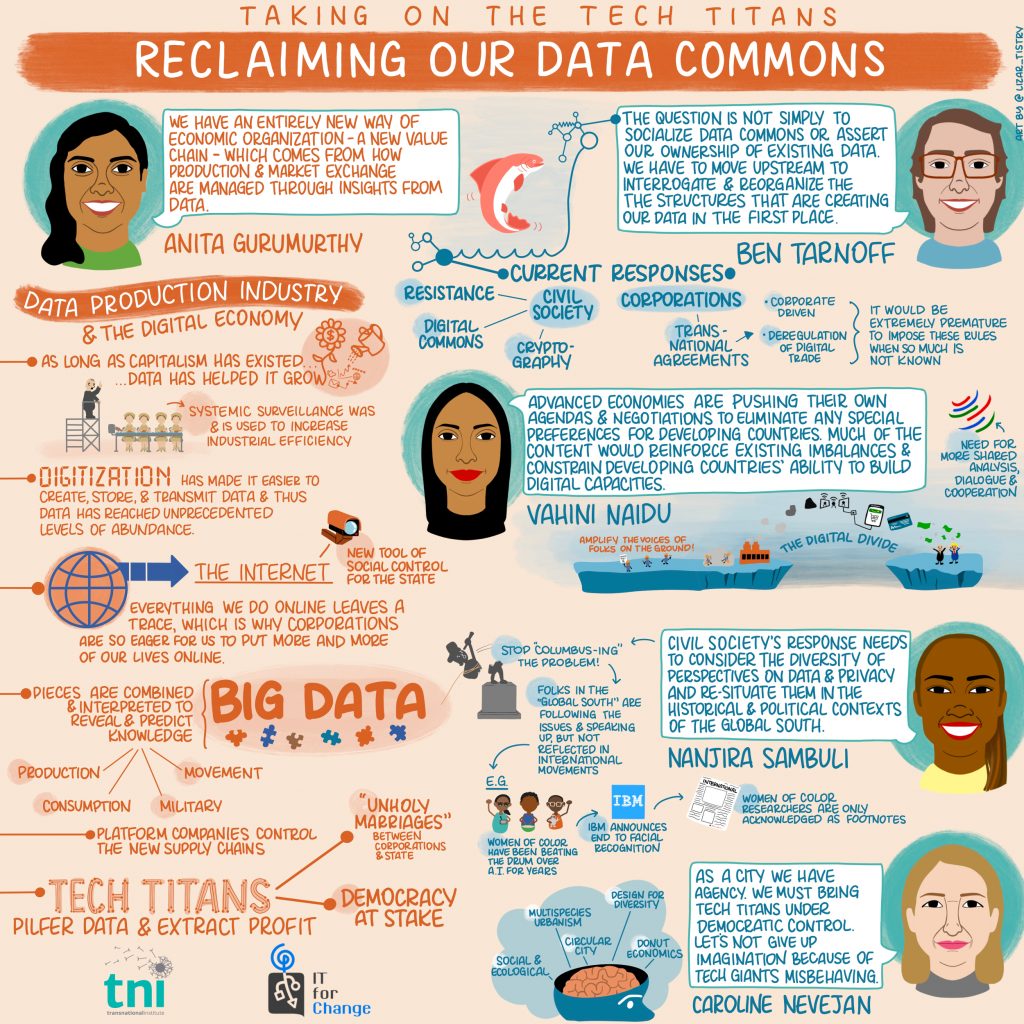

Chapter Ten – Taking on the Tech Titans: Reclaiming our data commons

“We must not fixate on what this new arsenal of digital technologies allows us to do without first inquiring what is worth doing.” Evgeny Morozov

The pandemic has accelerated the use and profits of large online platforms, giving them unprecedented power over how we conduct our everyday lives. The panel discussed who owns our data, how we can protect our right to privacy in the face of big tech, and the best ways to build a fair and equitable digital economy.

Analysis

According to founding editor of technology magazine Logic Ben Tarnoff, digitisation now is as important to capitalism as financialisation was in the 1970s. It is the new engine of capital accumulation and offers states innovative tools of social control to help manage and order rebellious populations, with the COVID-19 crisis only intensifying developments. Globally, unprecedented numbers of people are staying at home and there has been a sharp increase in internet usage, with traffic 25–30 per cent higher than before. Big data is driving the digitisation of everything as corporations make it easier for us to do more online, yet ‘everything we do online leaves a trace’.

‘As long as capitalism has existed’, Tarnoff argues, ‘data has helped it grow’ – from bosses watching employees work then rearranging them to be more efficient, surveillance generated information has been used to increase productivity. Digitisation makes data more abundant – it has become easier to create, store, transmit – and a small device can be attached to anything to stream real-time information: shipping containers, assembly lines, gas turbines, and the wrist of a worker in a factory or office.

Vahini Naidu of the South African Department of Trade, Industry and Competition has witnessed advanced economies pushing their own agendas within the World Trade Organisation, pursuing a deregulatory approach to digital trade. Big Tech companies believe there should not be any customs, duties, or fees on digital products transmitted electronically, and argue that consumers will decide how secure their electronic transactions should be. These proposals reinforce existing global imbalances, constraining the ability of developing countries to build their own digital capacities – the ‘digital divide will reinforce the social divides in the world’. Digital capacity is essential to build productive capacity, especially for countries in the Global South in pursuit of sustainable growth.

Anita Gurumurthy, Director of IT for Change in India, sees all global production and market exchange managed through insights from data. ‘Platforms’ dominate the business landscape today and their power is growing at breathtaking speed. Large companies work out which other companies to acquire and how to expand their dominions based on ‘data marriages’ – no different from how royal families once decided to fix the marriages of sons and daughters based on political and economic considerations. Thus, a company like Whole Foods can be acquired by Amazon to ‘marry’ its online commerce with a new and booming offline market for organic foods.

Chief Science Officer of the City of Amsterdam Caroline Nevejan argues that because of data we have moved from measuring individual human beings to measuring humankind – we now know ‘what many people can feel, think, and see’. Big Tech is invading our private lives, financialising aspects which were never previously concerned with money. As we lose our personal privacy, we are given little information about how our data is used by large corporations to extract profit.

Kenyan technology writer Nanjira Sambuli feels we need a greater degree of ‘contextualisation and humility’ when dealing with issues of data and privacy, especially in the Global South – ‘the diverse and marginalised majority of the globe’. These markets are ‘prized possessions’ in the data economy. While activists should continue to advocate for laws and regulations protecting data and privacy, they must also understand that this is not necessarily reflective of what much of society wants. Deleting Facebook or WhatsApp, for example – ‘the internet for so many people’ – may be a growing political demand in the North, but at present is impractical for substantial numbers of citizens in developing countries without alternatives in place.

Solutions

The panel explored pressuring governments to constrain the excesses of big tech, ways of reclaiming our personal data, and how countries – especially in the Global South – can achieve ‘digital sovereignty’.

Ben Tarnoff warns civil society that it cannot simply call for data to be ‘socialised’ as currently ‘capitalism doesn’t just own the data – it owns the infrastructure’. The increasing demand for invasive state and corporate surveillance should be confronted – during the pandemic, personal data has been gathered through contact tracing, monitoring location and body temperature, facial recognition, and wearable technology in the workplace.

Vahini Naidu believes in the need to develop policies that recognise the ‘sovereignty of national data’. The ‘localisation’ of data provides an opportunity for the Global South to tie up its domestic industries with the digital economy. While the European Union is ‘taking the lead’ in confronting

Big Tech companies, only 50 per cent of African countries have introduced legislation regarding privacy and data protection.

Anita Gurumurthy calls on people to interrogate who controls new supply chains and how to reclaim data for ‘the commons’. To build an equitable and fair digital economy, the huge discrepancy between the economic superpowers and the rest of the world must be addressed – 75 per cent of the cloud computing market is controlled by the US and China. Campaigners should find ways of freeing the personal information Big Tech companies hold hostage – which amounts to ‘the raw material’ that allows an invasion into private lives and ultimately leads to exploitation.

Caroline Nevejan asserts that it is ‘not normal to be filmed’ throughout daily life. Citizens need to learn and practice cryptography in order to protect their personal details. This should happen in conjunction with helping to bring the tech titans under democratic law – data about their operations is important for transparency and exposing any corruption that may be taking place, so civil society must demand that this information be put into the public domain.

Nanjira Sambuli suggests that because many people ‘can’t take to the streets during COVID-19’, activism is increasingly undertaken online – using the same large global platforms, like Facebook, that many activists wish to see deleted. International civil society must consider a ‘diversity of perspectives’ on digital rights and ensure to ‘give a spotlight to those working on the ground’.

Further resources: Evgeny Morozov: The tech ‘solutions’ for coronavirus take the surveillance state to the next level (April 2020) The Guardian

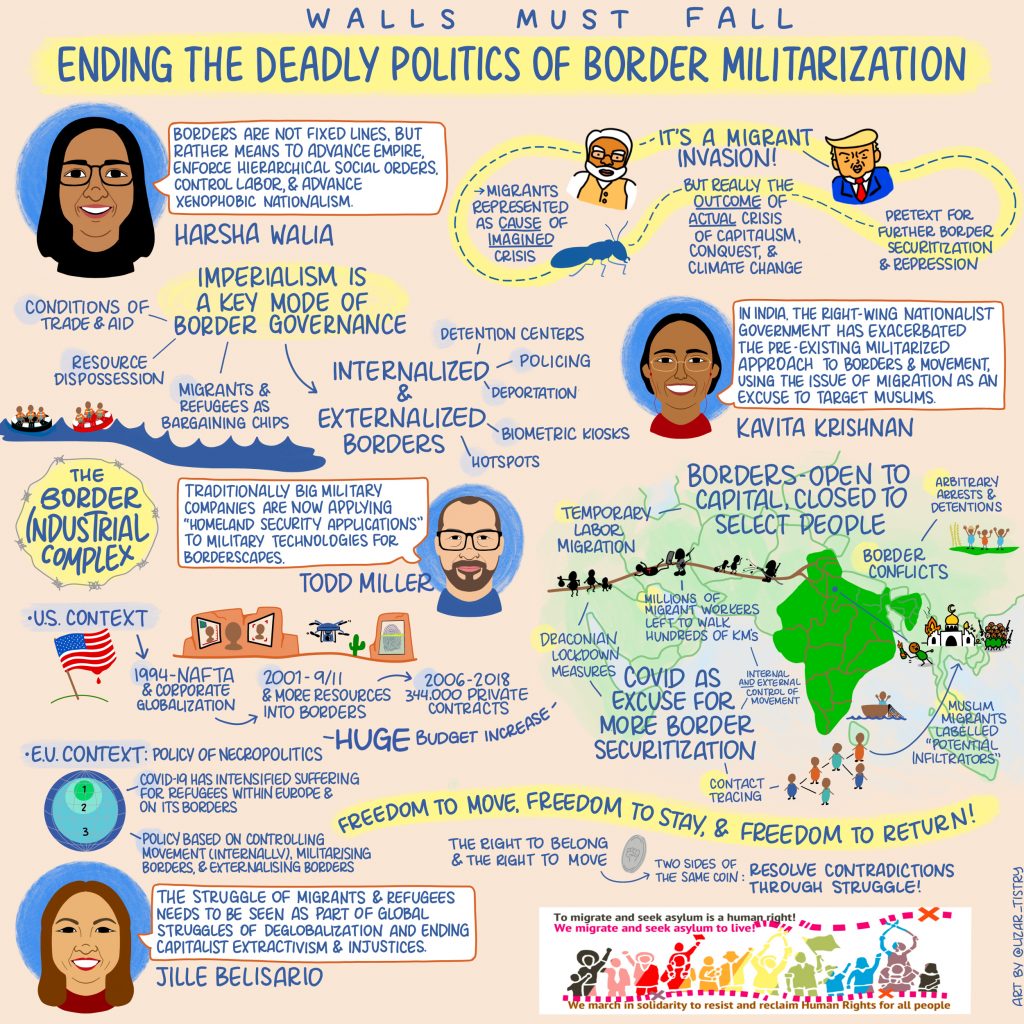

Chapter Eleven – Walls Must Fall: Ending the deadly politics of border militarisation

‘Governments are responding to this pandemic with nationalist gestures – with images of the border, of the wall.’ Achille Mbembe

The pandemic has seen the closure of borders in many countries and displaced people detained at alarming rates. The panel looked at how the ‘border-industrial complex’ impacts upon the most marginalised communities, and the ways populist politicians seek to blame the spread of the disease on migrants and those deemed outsiders.

Analysis

According to author of Undoing Border Imperialism Harsha Walia, walls are not to be seen as ‘static structures’ – borders are ‘elastic’, their existence less about demarcating territory and more linked to controlling labour flows. European border policies have considerable influence over regions in North Africa; Australia extends its reach to the Pacific islands. In exchange for trade and aid agreements, poorer nations are compelled to impose increased border controls, off-shore detention facilities, migration prevention campaigns as well as admitting expelled deportees.

The ‘free flow of capital requires precarious labour’ underpinning contemporary policies of ‘managed migration’. An asymmetry sees tourists and expats given different legal rights to refugees and asylum seekers, ‘bargaining chips’ in immigration diplomacy. The language used to describe the ‘migrant crisis’ has Western nations presented as its victims – their past colonialism ‘conveniently erased’ – while the migrant is depicted as its cause, not an outcome of the actual crises of capitalism, conquest and climate change.

Todd Miller, author of Empire of Borders and Transnational Institute’s More Than A Wall report, interrogates the United States’ ‘border-industrial complex’, believing that public focus on the Trump administration’s infamous pledge to ‘build a wall’ along US-Mexico lines erases the nation’s long trajectory of border militarisation. There has been an ‘astronomic’ increase in funding the expansion of immigration enforcement apparatus over a number of presidencies – both Republican and Democratic. In 1994 the annual budget was $1.5 billion; by 2019 it was $24 billion. Public bodies like Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) spend billions of dollars on private contracts, creating ‘borderscapes’ to deploy drones, robots, biometrics, and hi-tech cameras to monitor the movement of people. Beyond national boundaries, the US government pressures neighbouring states in the Caribbean and Central America to build up their border security, while American companies such as Raytheon operate facilities further abroad in the Philippines and Jordan.

Jille Belisario of Transnational Migrant Platform-Europe understands that migration has always played a role in human development, and always will. In Europe, several countries have used the COVID-19 spread as an excuse to suspend access to asylum, with populist politicians painting migration as a threat to containing the virus. There have been reports of violent pushbacks on the Croatia-Bosnia border, while Maltese and Greek authorities have deported incomers to areas outside their jurisdiction. The externalisation of Europe’s borders to Turkey, North Africa and beyond has become ‘the new normal’.

Kavita Krishnan of the All India Progressive Women’s Association (AIPWA) believes that daily life is extremely precarious for ordinary citizens in border regions and for the many migrant workers being forced out of India’s cities during COVID-19. This is part of a historical pattern in which migrants and refugees have experienced waves of conflict and repression. Under Modi, existing tensions between a nationalist state and those it considers outsiders have been exacerbated. Aggressive contact tracing is used to surveille potential infiltrators, rather than focus on helping those most in need, while the criminalisation of ‘illegal migrants’ and marginalisation of the country’s Muslim population frequently lead to inhumane treatment and violence against those opposing reactionary citizenship laws.

Solutions

The panel outlined ways to resist growing anti-migrant sentiment, secure rights for the undocumented, and encourage solidarity across borders.

Harsha Walia feels that to secure people’s ‘freedom to move, stay, return’, campaigners will have to make connections between differing experiences of oppression. Artificial divisions between activist movements must be broken down – in the north American context, black liberation, indigenous and migrant struggles are often seen as separate, and yet the same ‘white vigilantes’ will cause concern for each group.

Todd Miller finds the sheer scale of the global border system ‘astonishing’, and its continuing growth ‘unsustainable’. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 there were 15 fortified border walls – now there are more than 70, two-thirds of which were built after 9/11. Civil society must keep track of the ‘pushing out’ of US borders and the European Union’s extension of its boundaries, which see armed guards and billions of dollars of technology deployed to Western allies across the world.

Jille Belisario says the biggest challenge for civil society is to find ‘strategies of convergence’ between border politics and other social issues. People who have experienced migration should be considered key parts of other progressive struggles – from trade union and peasant rights to improved conditions for domestic and care workers. There is ‘a lot of positive activism and resistance’ around borders taking place including the Permanent People’s Tribunal which has held hearings in five European cities, supported by 500 organisations.