This essay is part of the book Public Finance for the Future We Want, you can find the entire collection of essays here.

Local initiatives can lead to modest gains in social and ecological sustainability, but not the large-scale transformation we need. Meeting that challenge will require, among other critical factors, substantial changes in how we create and use money. It is the privatization of money – and not money itself – that has fueled social exploitation and environmental destruction. Money could, by contrast, help foster the future we want but only if it is reclaimed for the public. Contrary to neoliberal assertions, the state can create money free of the debt that drives destructive growth and fosters inequality. Such public money can facilitate the provision of economic security, universal basic services and sustainable livelihoods for all. But for such a system of public money to work, there must be robust democratic control over monetary decision-making along with vigorous oversight of its implementation.

The key role of money

If we want to transition to a more just and sustainable society, we then need to be clear about where we are today.1 In the contemporary world, provisioning, that is the creation and distribution of basic goods and services, depends on money.2 Most people live in market economies with moderate- to long-distance supply chains. Under market-driven capitalism, individual livelihoods and public services depend on the success of the market, and money functions both as the medium of exchange and as the driving force behind market participation. The primary aim of the capitalist market economy is not the provision of essential goods and services for the people, but the investment of money and labour in activities that provide even more money (i.e. profit) for the owners of capital. This results in a two-step economy: people work to secure an income in order to pay for the basic goods and services they need to survive. And because work is necessary for survival, and the market determines its purpose and availability, people can end up in jobs that are harmful to them, others and the environment.

Using money does not intrinsically encourage human exploitation or ecological destruction. It is neoliberal capitalist ideology that puts monetary gain above social and ecological concerns, and it is the private, bank-issued money system that leaves us with a pernicious cycle of debt and growth. Money could encourage socially and ecologically sustainable production and consumption, but only if it ceases to be a creature of the market and is reclaimed as a social and public representation of value.

Visions of ecologically sustainable communities often look not to the state, but to the social economy, which occupies a space between the state and the market.3 Key features of the social economy such as community enterprises, cooperatives and local markets based on local money are all beneficial, but they are insufficient for transforming the political economy. Creating a just and sustainable future is a massive undertaking that will require a level of coordination that only the state can provide. We thus need to look at the potential of democratically governed economies in which money is treated as a public resource for sustainable provisioning.

However, neoliberalism, which has influenced so much of the conventional thinking about money, is adamant that the public sector must not create (‘print’) money, and so public expenditure must be limited to what the market can ‘afford’. Money, in this view, is a limited resource that the market ensures will be used efficiently. In the conventional view, the state is dependent on tax revenue extracted from the ‘wealth-creating’ private sector. Public expenditure is a burden on the hard-working taxpayer – who is almost never portrayed as a beneficiary of public services. If money is created exclusively by the commercial sector, the conventional view is in many respects correct. The public sector is dependent on the money raised by taxation, and absent borrowing, taxation must precede public expenditure.

Is public money, then, a pipe dream? No, for the 2008 financial crisis and the response to it undermined this neoliberal dogma. The financial sector mismanaged its role as a source of money so badly that the state had to step in and provide unlimited monetary backing to rescue it. The creation of money out of thin air by public authorities revealed the inherently political nature of money. But why, then, was the power to create money ceded to the private sector in the first place, and with so little public accountability? And if money can be created to serve the banks, why not to benefit people and the environment?

Myths about money

One of the most significant obstacles to reclaiming money for the public good is the widespread misunderstanding of what money is. The conventional history of money rests on a series of myths that obscure its social and political origins. The first myth is that money and the market share a common origin, with modern money-based economies emerging from non-money barter. There is no historical evidence of widespread barter-based economies, and money, as the next section will explain, has a far more complex social and political history. The second myth is that money originated as precious metal coinage. While money has at times been made of such metal, it has also taken far less valuable forms whose use long predated the invention of coinage. Seeing money as made of something valuable (gold, silver) suggests that money is desirable in itself, an embodiment of value. Recognizing that money is valueless in itself (base metal, wood, paper) helps one to see it as a token representing a social relationship – what it really is.

Assumptions about the historical importance of precious metal coinage gave rise to a third myth: that banking activity emerged from the management of precious metal deposits that eventually came to be represented by paper money and accounting records. In reality, banking activity originated long before precious metal coinage, with accounting records as a central feature. This historical misapprehension, in turn, helped create a fourth myth: that banks today are merely link savers (depositors) and borrowers. As has been increasingly recognized by the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the International Monetary Fund, and long argued by monetary theorists, in fact banks create new money when they make loans, crediting deposits of previously nonexistent money to the accounts of those who receive them. Public monetary authorities retain a monopoly on the production of cash (notes and coin), but the money that banks create is also part of the national money supply and circulates through the economy as such.

These widespread myths all rest on a misreading of the history of money. So what is the real history?

A brief history of money

Far from being a product of markets, coinage was created and controlled by rulers and played a central role in the growth of the Greek and Roman empires. The power to create and circulate money is likewise linked to the sovereign power to tax. Rather than relying on the traditional receipt of tribute, a ruler could pay for goods and services with money that could later be reclaimed through taxation.

The emergence of the capitalist epoch, with its paper promises and modern banking, saw the gradual privatization of the sovereign’s power to create money. A crucial step in this privatization process was when commercial money became the public currency. The Bank of England, for example, was originally formed in 1694 to make loans to the state. As time passed, its notes, backed by a nebulous ‘promise to pay’, were designated as currency. Eventually, all banks stopped issuing money in their own names, instead issuing it as public currency (e.g. pounds sterling). This step resulted in two major changes. First, the public became the backstop for the banks that were creating money in its name. Second, whereas the sovereign could create money free of debt, the banks could not. Money created and lent by banks must be repaid with interest. This critical difference drives growth because new debt is created to repay old debt. And if this debt-based sys- tem falters, so, too, does the money supply.

Today, our reliance on debt has become socially, ecologically and econom- ically unsustainable. It is socially unsustainable because creating money as debt exacerbates inequality. Money flows to those most able to pay back loans with interest, a dynamic that enriches the rich and traps the poor in long-term debt relationships. Debt is ecologically unsustainable as it drives growth. If debts are to be repaid and a profit made, the economy must grow, with likely environmental consequences. Debt is economically unsus- tainable as the source of a money supply because there will come a time when people can take no more debt.

Reclaiming money for the people

The social and public heritage of money needs to be reclaimed and its gov- ernance democratized. Money can represent social and public value, not just commercial and private value. And rather than being only a mechanism for profit-driven exchange, money can be a tool for the provision of public goods and services people actually need and for guaranteeing everyone a right to livelihood, for example, through a basic income (i.e. a monetary allocation to each individual as matter of right).

While the commercial use of money drives growth, the public and social allocation of money would provide people with the basic goods and services they need to survive, thereby supporting a one-step rather than two-step economy. The development of a one-step economy is essential to publicly fund a just and sustainable society. By relieving people of the need to undertake unsustainable and unnecessary work in order to obtain money, it would reduce ecological strain and economic inequality.

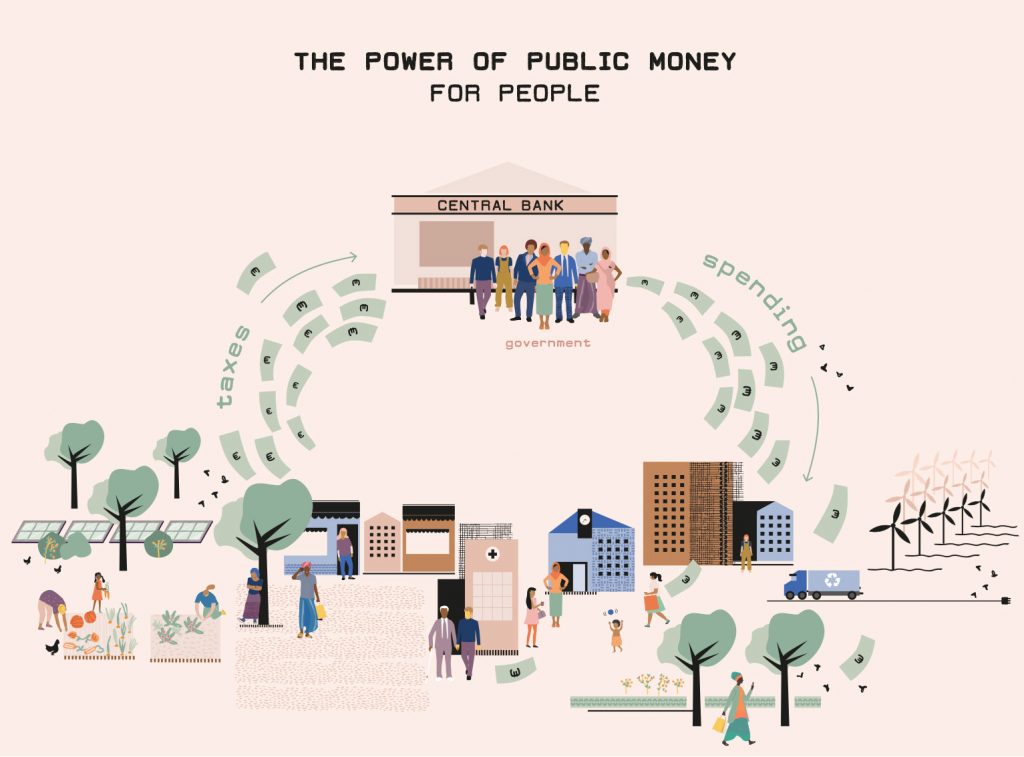

Neoliberal economics denies that all of this is possible. Indeed, politicians routinely claim that there is ‘not enough money’ for our basic needs. But despite the claims and strictures of neoliberal ideology, states can and do ‘print money’. First, it is produced ex nihilo by central banks to provide cash and support for the money-creating activities of the banking sector. Second, money is created and circulated as the government spends, in the same way that banks create money as they lend. States spend money and then offset their expenditures against tax revenue and other income received. States, however, do not fill their tax accounts before they spend: the balance between public expenditure and public income only becomes clear after the expenditures have occurred. The political choice at that point is what to do with any ‘deficit’, that is, the surplus of expenditure over income. The extra money created by state expenditures could be left to flow around the economy, producing in effect a perennial ‘overdraft’ at the national bank. Or the deficit could be shifted to the financial sector through ‘government borrowing’, thereby increasing the national debt (as happens in most capitalist economies).

Control of the money supply and, more generally, the monetary system confers a tremendous amount of power. Can we entrust the state with it? Neoliberals warn of the dangers of state intervention in a market-based system. Proponents of social and local economies likewise harbour suspicions of the state, particularly its distant and opaque bureaucratic apparatuses. Therefore a public money system would be acceptable only if it was robustly democratic.

Democratizing money

A shift from profits to provisioning would put the main focus of the economy where it belongs: on the sustainable meeting of needs. That goal would be met through a combination of a basic income and a budget for collective expenditures on universal basic services and infrastructure (i.e. free public services that enable every citizen to live a larger life by ensuring access to safety, opportunity and participation).4 The democratic process would entail the development of party platforms followed by participatory budgeting, in the process described below.

At national and regional levels, political parties would propose an overall allocation of funds among the social, public and commercial sectors – as well as levels for the basic income – as part of their election platforms. Actual allocations would be those of the parties in power. Money to fund these democratically determined allocations would be provided through grants or loans administered by banks, using funds provided by the central bank and operating under social, public or cooperative structures. In this process, the utilitarian purpose of banks – holding deposits, conducting transactions and balancing accounts – would be preserved, but they would no longer be able to create money or engage in speculative finance. Where the private sector requires loans for sustainable and socially just investment, this would be accommodated by either an allocation of public money via these banks for lending or a transfer of existing money from private investors.

Public expenditure would be through direct spending of money created free of debt. Citizen and user-producer forums would identify specific public expenditure needs, providing input into local, regional and national budgets. Given the complexity of the process, these budgets and the corresponding allocations would be set for at least a five-year period, with a modest margin for interim adjustments. Adoption of a participatory and transparent approach to decision-making would militate against domination by any particular group or body. The setting of long-term budgets would ensure that governments could not substantially amend proposed money creation or expenditure levels during the run-up to elections.

Because such a system would be likely to result in a massive increase in public expenditure, a phase-in would be prudent. The size of the public economy could be gradually increased each year until public needs were fully met. Even with that, the additional money flowing into the market sector could increase the threat of inflation in the short term. Reconceptualizing the role of taxation offers a way to address the problem of inflation. If money is created and circulated initially by the public sector, then there is no need to ‘raise’ money through taxation. Rather than preceding public expenditure, taxation would follow it, retrieving publicly created money from circulation in amounts sufficient to keep inflation in check. If the public sector is much larger than the private sector, taxes might have to be quite high.

While levels of budgets and universal basic services and incomes can be determined through an open, democratic process, the assessment of the impact of public expenditure on the commercial sector would require technical expertise. This situation is no different from what we see today: experts in monetary policy try to anticipate and then propose actions to address inflationary pressure, usually by adjusting key interest rates. As is the case today, estimating the impact of public expenditures would be a hit-or-miss process, but a necessary one nonetheless. A committee of experts would assess the amount of public money the commercial sector could absorb without too great a rate of inflation and, correspondingly, the overall level of taxation required. The expert assessment would have no role in determining public expenditure levels or how the required taxes would be applied; the public would come in, debating questions of what amount to spend and whom, what and how much to tax.

The model of public money and taxation just described reflects how money flowed before the commercial domination of the monetary system. Sovereign rulers issued money in various forms to pay for goods and services and then retrieved the money through taxation. Today, the people should be the sovereign. Under a system of public money, the people would make payments to themselves for goods and services provided for their own benefit, then take that money back via taxation.

Effectively exercising the public’s right to create and spend its money would require a wide range of democratic decision-making. Questions about the level of taxes, redistribution of income and wealth, whether to tax resource use or land, which expenditures should be taxed, and so on, would need to be democratically determined. However, given the basic income and extensive free public services included in the proposal, there would be much less need for the accumulation of wealth or for investment programmes such as pensions, which are major drivers of growth. This, in turn, would justify even greater taxes on existing wealth. Moreover, since there would be less need for investment opportunities, public money could be created and used to purchase natural resources and utilities currently in private hands, bringing them back under public control.

Another important focus of democratic participation would be the enhancement of public spending oversight. All recipient organizations of direct or indirect allocation of public money would need to have clear mechanisms for democratic accountability and transparency in place. Interested citizens along with workers and user groups would monitor their expenditures and business practices on a regular basis. Such monitoring would minimize the possibility for abuses, such as over-leveraging of the financial sector and corruption in the public sector, which have plagued the current system.

Conclusion: Debt-free public money for sufficiency provisioning

A public money system would enable a one-step economy in which individuals no longer have to undertake socially or ecologically harmful work in order to secure an income. Participation in the market would no longer be essential, as money would reflect an entitlement to livelihood, not just the market value assigned to work. Paid work would continue, but it would focus on democratically determined priorities. Caring for each other and for the planet and building a just society, not financial speculation and resource extraction, would be recognized as the real sources of wealth. New metrics would track and guide progress, with a shift from gross domestic product to a notion of ‘gross domestic provisioning’ that measures overall ‘wellth,’ that is, well-being.

In a transition towards an economy that prioritizes provisioning over profit, we must be attuned to the interplay between meeting our own needs and protecting the environment. For example, substantially reducing energy use would have profound effects on domestic work, as the latter would be much harder without labour-saving (but energy-using) devices. Birth control has helped reduce environmental strain by keeping population growth in check. But slower population growth, or even decline, has also led to aging populations with relatively fewer people available for both productive and care work. A major focus of a future provisioning system will, therefore, need to be care for the elderly. Although today this responsibility tends to fall upon the shoulders of women as unpaid or underpaid work, it can become a major source of meaningful work and societal wealth.

Reorganizing the economy around publicly created money is not utopian. It simply requires recognizing and reorienting what has existed in the past and what we, in fact, fall back upon today. In the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-08, the power of public money was made clear when governments used it to rescue the banks and other large businesses, such as auto manufacturers and insurance companies. Let it now be used to provision the people.

This chapter is adapted from Mary Mellor’s ‘Money for the People’ originally published in Great Transition Initiative: Toward A Transformative Vision and Praxis in August 2017 and available on www.greattransition.org.

About the author

Mary Mellor is Emeritus Professor at Northumbria University, UK. She has published extensively on the democratization of money as a public resource, sustainability and social justice, ecofeminism and social economy. Her most recent books are The Future of Money (2010), Debt or Democracy (2015) and The Magic of Money (2019).

Notes

1 This chapter is based on my book: Mellor, M. (2015) Debt or Democracy: Public money for sustain ability and social justice. London: Pluto Press.

2 This chapter adopts the feminist notion of “provisioning,” which embraces currently uncosted areas of human need and the resilience

3 For more information on the social economy, see OECD (2017) ‘Social Economy’. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/social-economy.htm.

4 For more information about Universal Basic Services, see Global Prosperity Institute (2017) Social prosperity for the future: A proposal for Universal Basic Services. London: London University. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/igp/sites/bartlett/files/universal_basic_services_-_ the_institute_for_global_prosperity_.pdf.